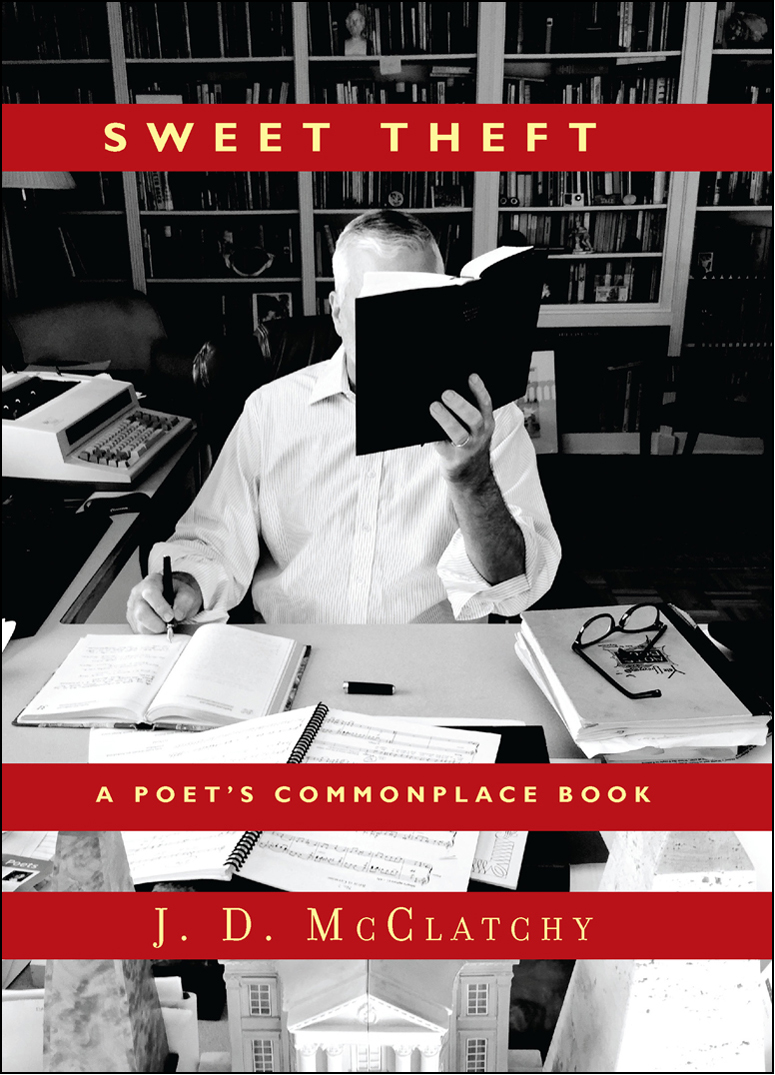

J. D. McClatchy - Sweet Theft: A Poets Commonplace Book

Here you can read online J. D. McClatchy - Sweet Theft: A Poets Commonplace Book full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2016, publisher: Catapult, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Sweet Theft: A Poets Commonplace Book

- Author:

- Publisher:Catapult

- Genre:

- Year:2016

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Sweet Theft: A Poets Commonplace Book: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Sweet Theft: A Poets Commonplace Book" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Sweet Theft: A Poets Commonplace Book — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Sweet Theft: A Poets Commonplace Book" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

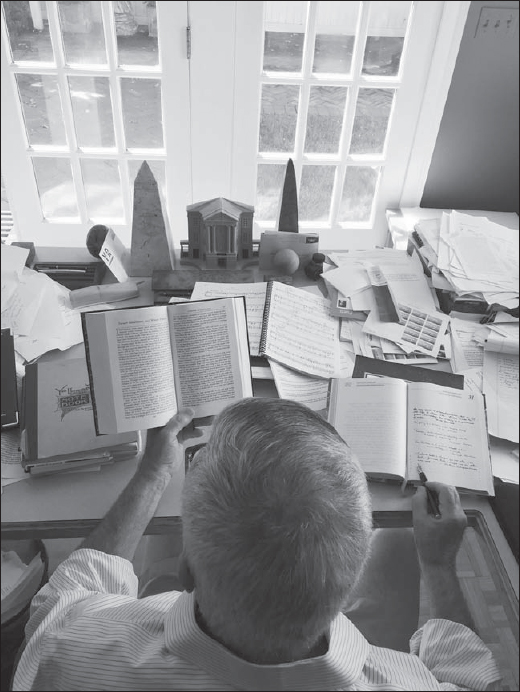

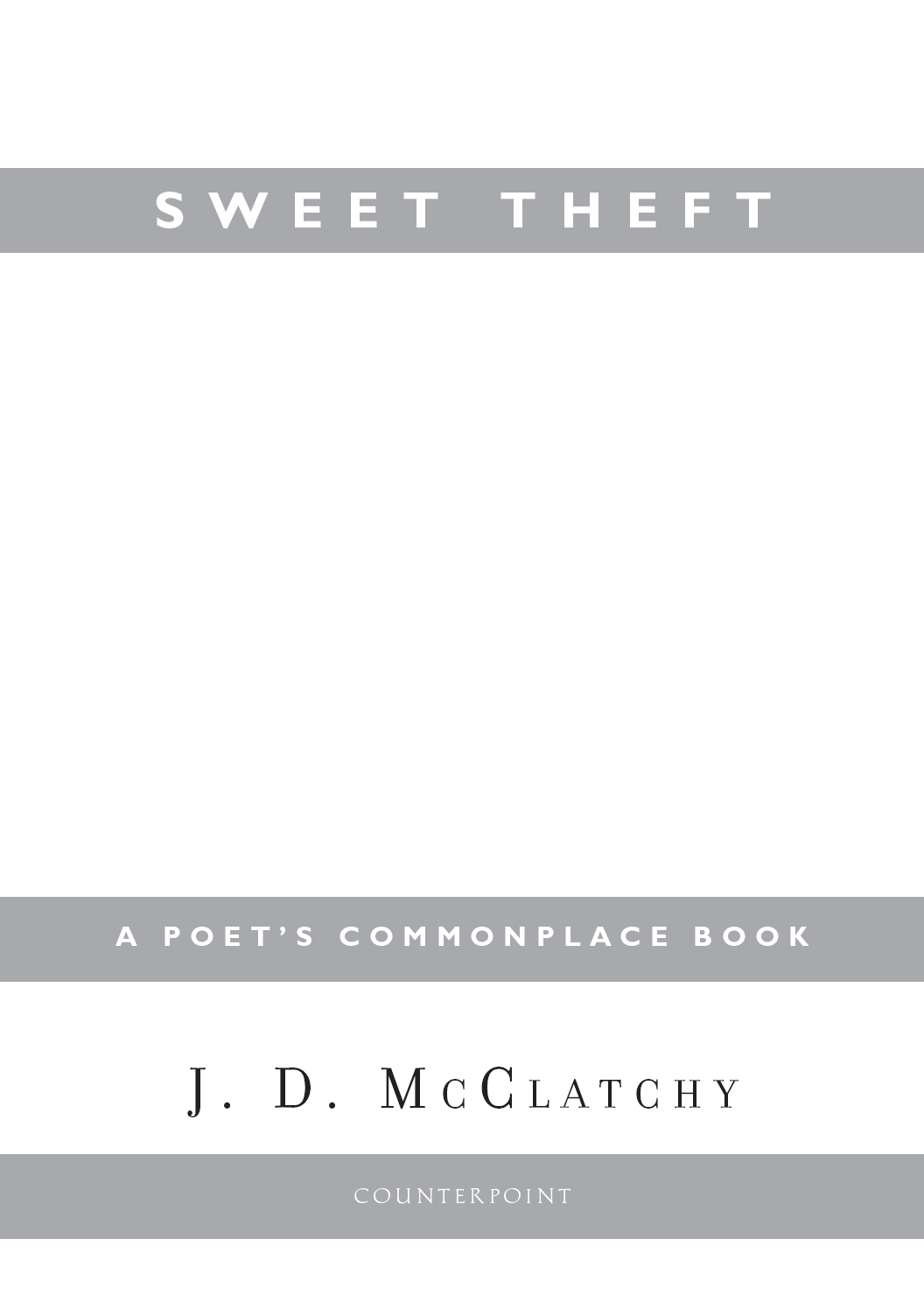

Copyright 2016 by J. D. McClatchy All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available Design by Chip Kidd Manuscript images from the collection of the author Other images curated by Eric Baker COUNTERPOINT 2560 Ninth Street, Suite 318 Berkeley, CA 94710 www.counterpointpress.com Distributed by Publishers Group West 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 e-book ISBN 978-1-61902-760-2 For Chip Kidd who has designed this book and everything else in my life for two decades now. Contents

Copyright 2016 by J. D. McClatchy All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available Design by Chip Kidd Manuscript images from the collection of the author Other images curated by Eric Baker COUNTERPOINT 2560 Ninth Street, Suite 318 Berkeley, CA 94710 www.counterpointpress.com Distributed by Publishers Group West 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 e-book ISBN 978-1-61902-760-2 For Chip Kidd who has designed this book and everything else in my life for two decades now. Contents  Tis no sin loves fruit to stealBut the sweet theft to reveal BEN JONSON I have from time to time kept both a notebook and a journal.

Tis no sin loves fruit to stealBut the sweet theft to reveal BEN JONSON I have from time to time kept both a notebook and a journal.They are very different things, as different as a recipe and the plat du jour. The one book I have scribbled in consistently over the past four decades, though, is my Commonplace book, a sort of ledger of envies and joys. By necessity, by proclivity,and by delight, we all quote, Emerson observed. I have been drawn to turns of phrase or bits of truth, and the best are combinations of bothas in the work of that sublime revolutionary wit Oscar Wilde. But there is more to it than that. And as G. K. K.

Chesterton once wrote: The original quality in any man of imagination is imagery. It is a thing like the landscape of his dreams; the sort of world he would like to make or in which he would wish to wander; the strange flora and fauna of his own secret planet; the sort of thing he likes to think about. The bower-bird in me is forever collecting colored threads and mirror-shards to make a sort of world. My secret planet is populated by Diana Vreeland and Dwight Eisenhower and Alexander Pope and John Cage and Edgar Degas and Dizzy Gillespie and hundreds of others: a Mad Hatters tea party of brilliant conversationalists talking over and at odds with one another. I dont use their remarks in my poems; I sometimes quote from them in my proseand can be seen here gathering possible ways of expressing my scorn or admiration. There is also a recurring character, named X, to whom phrases happen.

I have even included some musings of my own, pale by comparison with the wisdom of others but linked by the same impulse. I collect sentences because of the way, in each, something is put that is both precise and surprising. Twice-distilled poems? No. But an abstract model for the poetic. And if a poem is meant to be the light that casts a shadow, many of the entries in this book share the darkness of anyones skeptical or ironic sensibility. To minimize the risk of tedium, I have assembled here about half of the material I have copied down over the years.

Haste and blurry vision may occasionally have introduced some errors into my copying, but if the odd word is off, the sense is there. The range of this book is narrow but high-minded. It limits itself to the sources of art, the relationship of the page to the world, and to aesthetic prowess. But any meditation on art, of course, is a commentary on the lifefetid or fertile, domestic or abstruse, deliberately provocative and endlessly variedthat inspires and sustains it. Proverb or remark, aphorism or anecdote, each gem contains a chaos and functions as a prism, allowing us to contemplate what we didnt know we didnt know.Commonplace means proverbial wisdom. Sages from Cicero to Erasmus kept such books; they were meant to instruct, not to intrigue.

Orators and students would study the snippets from moral philosophy and great poems. When books were rare and passed from hand to hand, the keeping of such scrapbooks became a way to preserve favorite passages before having to return the book to its owner. Milton and Leopardi, Emerson and Hardy, E. M. Forster and Alec Guinness kept them. In the eighteenth century, they became more personal and idiosyncratic.

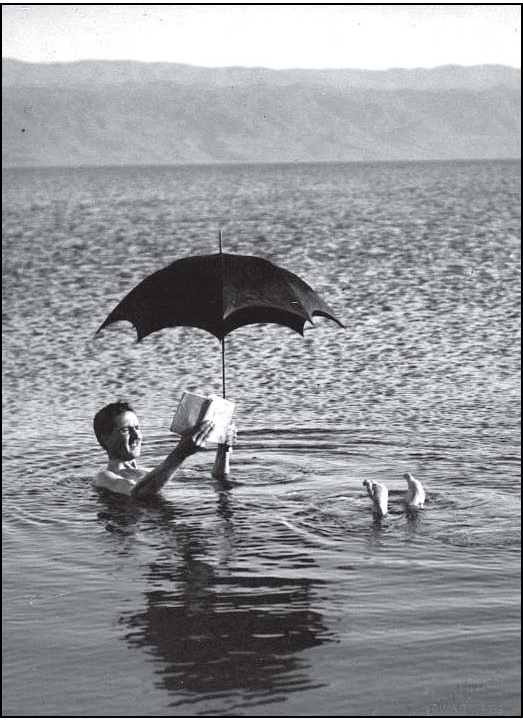

What once was considered an educational anthology the dictionary today defines as a personal journal in which quotable passages, literary excerpts, and comments are written. Emerson made it less a pastime than a noble cause, and gave it a revolutionary American slant: Make your own Bible. Select and collect all those words and sentences that in all your reading have been to you like the blast of a trumpet out of Shakespeare, Seneca, Moses, John and Paul.One old term for a commonplace book was silva rerum, a forest of things. My own favorite is W. H. Audens alphabetically-arranged A Certain World, published in 1970, a constant wonder of discovery and annotation.

Published near the end of his life, it is an emblem of the voracious appetite for knowledge that distinguishes his poems. He found appealing both the sacred and the camp.This book is meant to be sipped, not gulped. It is not necessarily meant to be read from beginning to end, but to be dipped into, a page or two savored at a time. I hope you wander at will through my forest of things and take from it a part of the pleasure I had in transcribing what the leaves said and the birds sang.JDMcC Robert Louis Stevenson: Sooner or later we all sit down to a banquet of consequences. - A Constant Lambert ditty: Its no good escaping your doomBy taking a ticket to Spain;The bulging portmanteaux of gloomWill arrive by a later train.- There is the story of Poussin impatiently dashing his sponge against his canvas, and producing the precise effect (the foam on a horses mouth) which he had been long and vainly laboring for. - Thophile Gautier told the Goncourts (Journals, March 3, 1862): The other day Flaubert said to me, Its finished. - Thophile Gautier told the Goncourts (Journals, March 3, 1862): The other day Flaubert said to me, Its finished.

Robert Louis Stevenson: Sooner or later we all sit down to a banquet of consequences. - A Constant Lambert ditty: Its no good escaping your doomBy taking a ticket to Spain;The bulging portmanteaux of gloomWill arrive by a later train.- There is the story of Poussin impatiently dashing his sponge against his canvas, and producing the precise effect (the foam on a horses mouth) which he had been long and vainly laboring for. - Thophile Gautier told the Goncourts (Journals, March 3, 1862): The other day Flaubert said to me, Its finished. - Thophile Gautier told the Goncourts (Journals, March 3, 1862): The other day Flaubert said to me, Its finished.

I have only ten more pages to write. But Ive already got the ends of the sentences. You see? He already had the music of the ends of the sentences which he hadnt yet begun. - Thomas Jefferson Hogg, in his Life of Shelley, tells of the celebrated mathematician at Cambridge who, at someones urging, finally read Paradise Lost. I have read your famous poem. I have read it attentively: but what does it prove? There is more instruction in half a page of Euclid! A man might read Miltons poem a hundred, aye, a thousand times, and he would never learn that the angles at the base of an isosceles triangle are equal! He further mentions a fussy, foolish little fellow, a banker in a country town, who once said to him: Would you suppose that much of Mr.

Wordsworths poetry was written in the dark; in total darkness. You will hardly credit it, but it is true, perfectly true! He went on to explain that the Lake bard was accustomed to place a pencil and paper by his bedside, and when a bright thought came to him, between the sheets, he wrote down instantly without striking a light, which was a slow process in an age of tinder-boxes, now obsolete, allowing time for fancies less volatile than emanations from the lakes to evaporate; and thus secured it for the benefit of posterity. Through long habit he was able to write correctly and legibly in the dark. Continuing, Hogg says that the sagacious little banker added, Any man, said the banker, who can write verses in the dark must be a real genuine poet; he must have it in him; there is no use in denying it. Only think! Just consider! There are poems in Mr. Wordsworths works that I am not by any means sure I could have written myself, either in the daylight, or in the evening, with two wax candles before me; but to have written them in the dark! There can be no mistake about him; we know very well what he is.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Sweet Theft: A Poets Commonplace Book»

Look at similar books to Sweet Theft: A Poets Commonplace Book. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Sweet Theft: A Poets Commonplace Book and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.