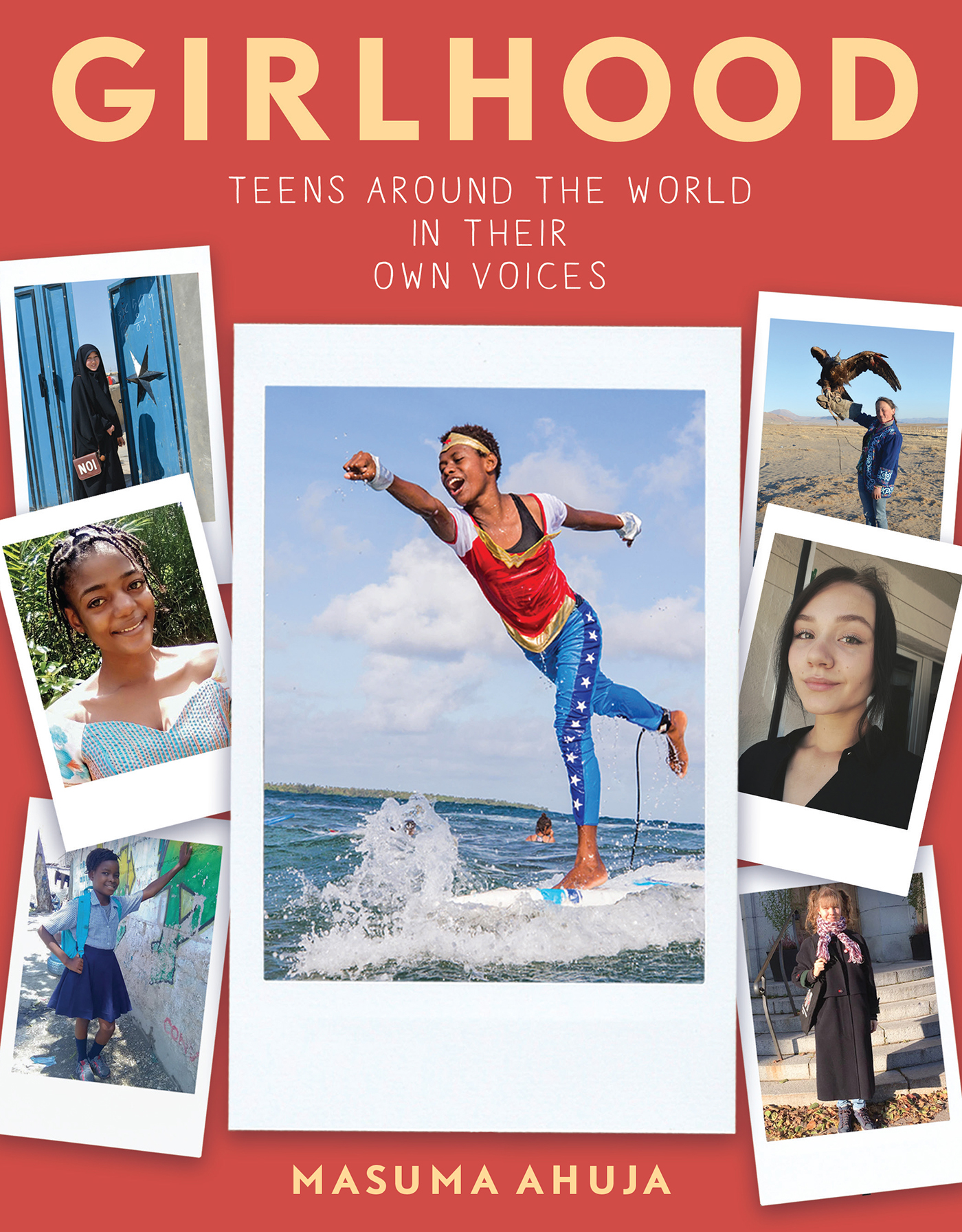

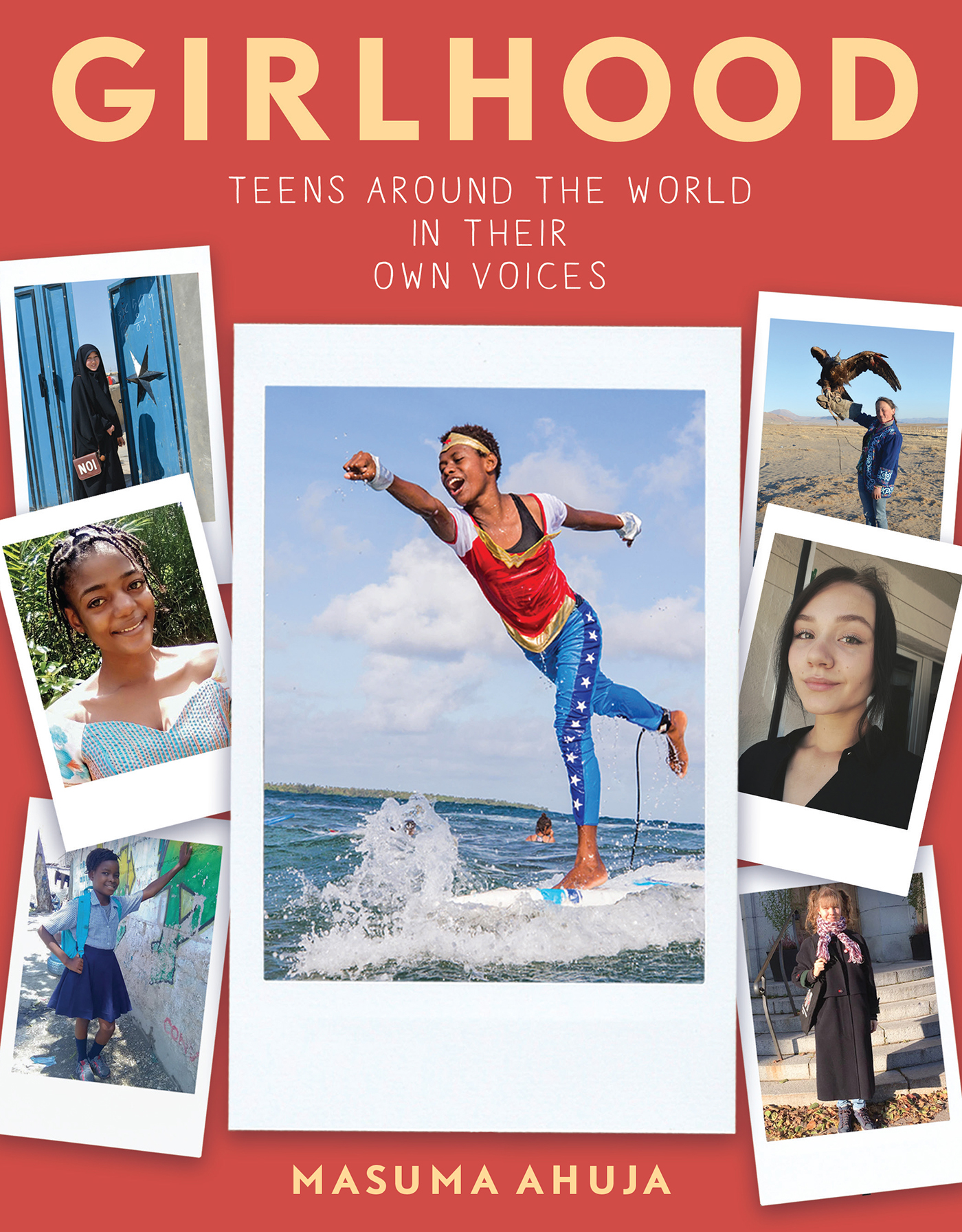

GIRLHOOD

TEENS AROUND THE WORLD IN THEIR OWN VOICES

MASUMA AHUJA

Algonquin 2021

For my parents, who always taught me that I could be any type of girl I wanted to be.

Contents

Introduction

Chen Xi stays up all night studying for a test. Miriam has butterflies in her stomach every time she talks to her crush. Merisena worries about her father getting hurt when he leaves for work. This is what girlhood looks like around the world.

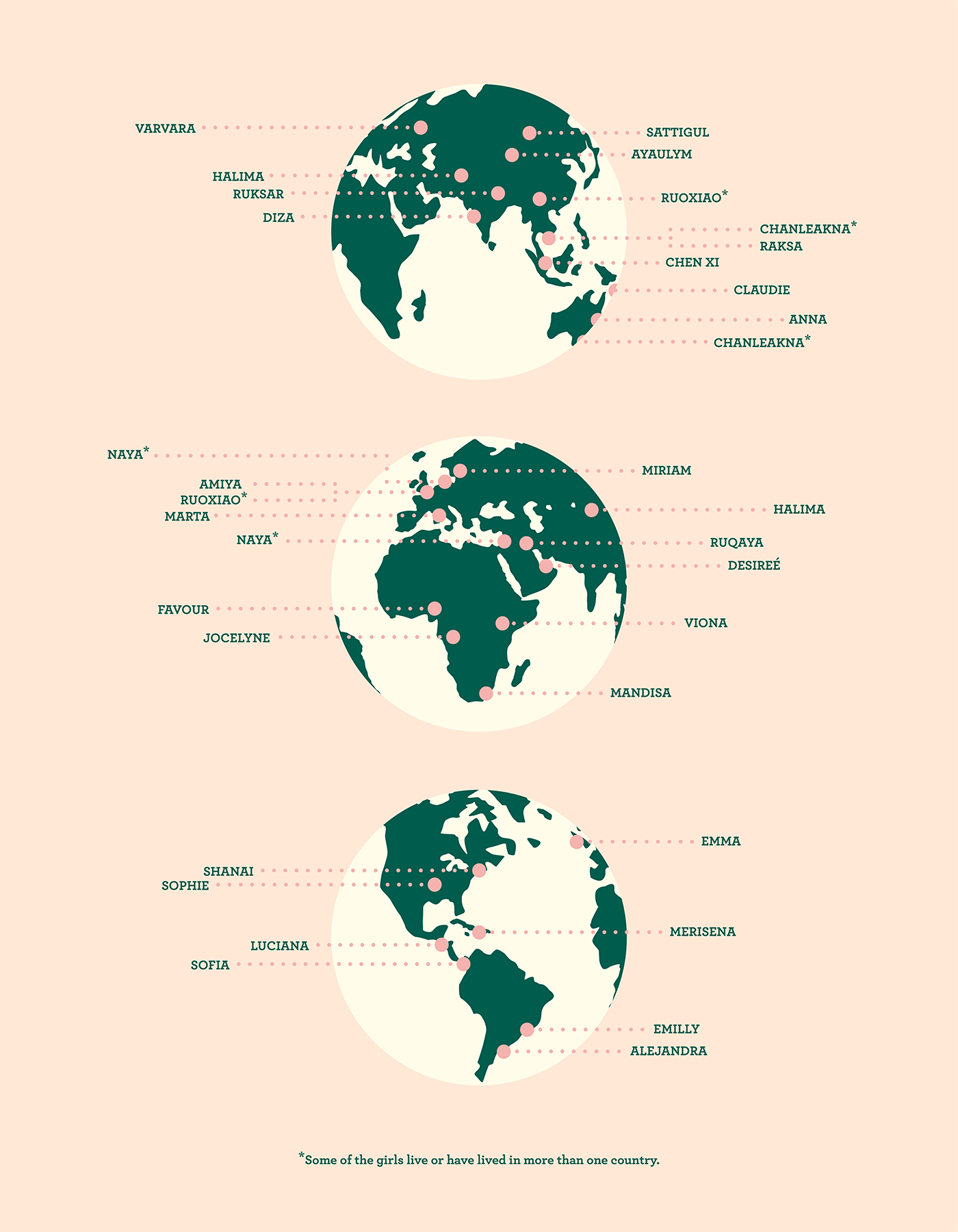

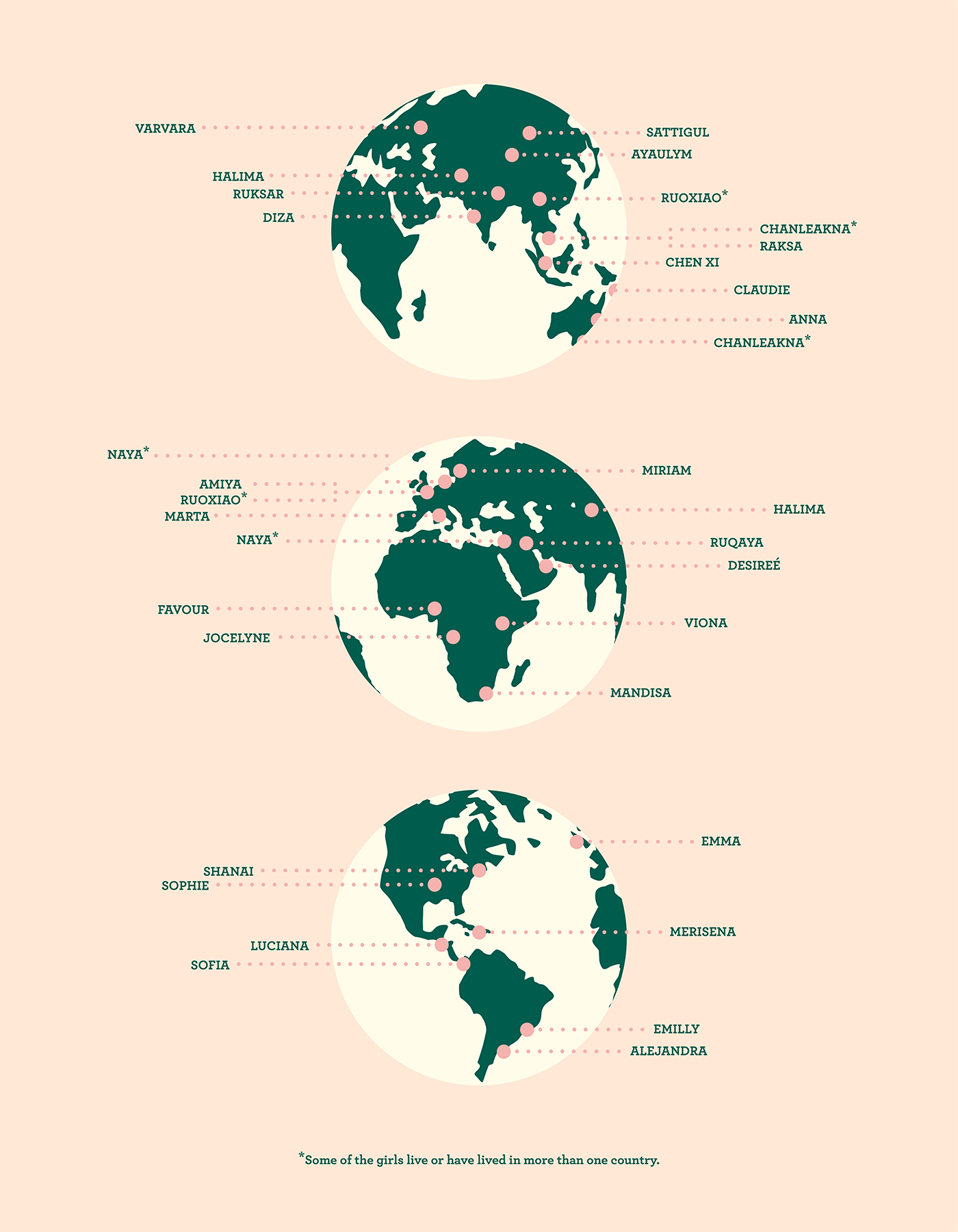

I asked thirty girls whose lives span twenty-seven countries to share diary entries and a few photos with us. I wanted to see their world through their eyes, and in their own words.

These are their stories about what it looks like to be a teenage girl moving through ordinary life in different contexts and circumstances, often at the edge of the headlines we read in the news. What does it mean to grow up in a family that had to flee a war? What do you dream of when you grow up in poverty? What is it like to raise a child as a teen mom? To deal with mental illness or eating disorders? What does it mean to navigate a crush or a breakup with your boyfriend or girlfriend? To balance friendship and fun with endless hours of homework and pressure to achieve? To figure out who you are and how to be a girl and a woman in our world, in the age of Instagram and Boko Haram?

If you go by the numbers from 2015 to 2018, this is what a portrait of girlhood around the world looks like:

One in five girls around the world marries before the age of 18. In fact, every single day, 41,000 girls under the age of 18 marry.

Every year, an estimated 16 million girls between the ages of 15 and 19 give birth.

About 130 million girls between the ages of 6 and 17 are not in school. Their parents might need them to work, they might be living in a place where its not safe to go to school because of violence, or they might be married or be mothers who are expected to stay home and take care of the family instead of going to school.

These facts paint a dark and dire picture, showing how the simple fact of being a girl can be political, and the many ways in which girls are silenced or policed. They highlight the prevalence of violence, repression, or abuse that girls face just because they are girls; laws that limit girls rights; and cultures that dictate how girls are allowed to dress, act, or live.

For example, in India and China, there are millions of missing girlsfemale fetuses are sometimes aborted because boys are preferred, or girls are neglected because families give more attention and resources to boys. In Afghanistan, millions of girls are out of school because of ongoing conflict, as schools have been bombed and burned, teachers abducted and attacked. In parts of Nigeria, girls have been abducted while going to school. Until 2020, in Tanzania, Equatorial Guinea, and Sierra Leoneall countries in sub-Saharan Africa, which has the highest rate of adolescent pregnancygirls were banned by law from going to school after they had children. These conditions arent limited to just Africa and Asia. In the United States, between 2010 and 2018, about 250,000 children under the age of 18 married; some were as young as 12 years old, and most of them were girls. Since 2016, states have started passing laws to ban child marriage, but many still do not have such laws on the books.

There are other important ways in which girls around the world are restricted. Cultures keep them off sports fields, and communities dissuade them from pursuing education and ambitious dreams.

These facts define the circumstances within which girls live, but beyond these headlines and circumstances, we rarely hear from girls themselves about what life is like for them.

We do get to see, on the other end of the spectrum, pieces of life from influencersfiltered updates, curated posts, life in snippets. Not the ordinary, humdrum stuff that fills most peoples days but never makes their feeds.

I wanted to know: What does a girl growing up in Iraq dream of? What does a girl in New York or Nigeria stay up nights thinking about? How would the story of girlhood be told if girls were the ones to write it?

The only way to find out, of course, was to ask girls themselves. So that is what I did.

This question led to a series I wrote for the Washington Posts The Lily, which featured twelve girls from ten different countries. This book was born from that series.

I gave each girl instructions for writing diary entries, but then I encouraged them to ignore those instructions and follow their instincts. I wanted to know what was on their minds, how they were spending their days, and how they were feeling.

Some girls had never written a diary entry before. Some girls chose instead to message me at the end of every day with updates. And others shared photos of journals theyd been keeping since childhood.

Because I asked for written entries, I could only include girls who have learned how to write and are comfortable with words. And these pages only feature girls who were able to share and who felt safe sharing their stories. How much and what you will read about each girls life was up to her. Each girl decided what to share with us, and how she would like to be represented. While the diary entries have been lightly edited for length and clarity, and some have been translated from their original language, they are all the work of the girls I interviewed.

To accompany each girls diary entries, I have researched and written about the context of her lifeabout her community, her circumstances, the themes she explores, or the country in which she livesto help you better understand the slice of life that each girl shares with us.

This book could not be comprehensivethere are more than a billion girls in the world, each with her own voice and her own story, and this is not an atlas of girlhood, after allbut I hope it is representative of a vast range of girls experiences.

Despite the differences of where they live, there is so much of life that looks the same across latitudes and longitudes, across borders and oceans: the daily moments of worrying about homework or laughing with friends, parents who just dont understand them, and plotting big dreams for the future. The girls explore what its like to feel like an outsider, to find friends and communities who understand them, to experience leaving home, and the ways in which theyre trying to make their plans and dreams come true. I hope the range of stories will help you see the different ways in which girls are navigating similar challenges as they begin to make sense of themselves and the world.

As I put this book together, I thought often about the only experience of girlhood that I am intimately familiar with: my own. My teenage years were split across three continents, and I rarely encountered stories like mine in popular culture. I read a lot growing up, but there were so few books about girls whose lives looked anything like mine. I caught glimpses in places, but they were rare. So I spent many of my teenage years explaining my other homes to people who often had only a few cultural references or stereotypesAmerica is like Friends and the Baby-Sitters Club, and India is the land of snake charmers. But in reality, life was so much more than any of these stereotypes or single stories.

In putting together this book, I found echoes of the emotions and types of experiences of my own teenage years. While the specifics of each life are differentand make for colorful and rich storiesmany of the themes that teenage girls experience and explore are similar: a longing for the adventures ahead, dreams burning big and bright, and the angst and growing pains of figuring out their own place in the world.

Next page