The Life of St. Benedict

The Great patriarch of the Western Monks (480-547 A.D.)

St. Gregory the Great (540-604 A.D.)

Nihil Obstat: Frowinus

Abbas Neo-Angelo Montanus

Imprimatur: Mauritius

Episcopus Sancti Josephi

St. Joseph, Missouri

March 4, 1910

Originally published in 1910 by the Benedictine Convent of Clyde, Missouri as part of the book Father Paul of Moll: A Flemish Benedictine and Wonder-Worker of the Nineteenth Century , by Edward van Speybrouck, which book was republished by TAN Books, an Imprint of Saint Benedict Press, LLC.

Library of Congress Catalog Card No.: 94-61773

ISBN: 978-0-89555-512-0

The type in this book is the property of TAN Books, an Imprint of Saint Benedict Press, LLC, and may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without written permission of the Publisher. (This restriction applies only to this type, not to quotations from the book.)

TAN Books

Charlotte, North Carolina

www.TANBooks.com

2012

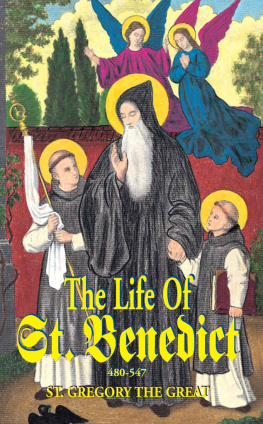

St. Benedict of Nursia (480-547 A.D.), Founder of the Benedictine Order and Father of Western monasticism, with St. Maurus (left) and St. Placidus (right) , two of his early youthful followers.

Beloved of God and men, whose memory is in benediction. He made him like the saints in glory, and magnified him in the fear of his enemies, and with his words he made prodigies to cease. He glorified him in the sight of kings, and gave him commandments in the sight of his people, and showed him His glory. He sanctified him in his faith, and meekness, and chose him out of all flesh. For He heard him, and his voice, and brought him into a cloud. And He gave him commandments before His face, and a law of life and instruction.

Epistle, Common of a Holy Abbot

From Ecclesiasticus 45:1-6

NOTE

The Life of St. Benedict (480-547 A.D.) was written in Latin by St. Gregory the Great (540-604 A.D.). The text of the English translation is taken, with very few changes, from an old manuscript dated 1638.

CONTENTS

Including The Vision of Anne Catherine Emmerich By St. Gregory the Great

INTRODUCTION

The life of St. Benedict is related to us by Pope St. Gregory the Great, who, being a relative of the great Patriarch and a member of his Order, was particularly qualified for this task. Pope Gregory was not personally acquainted with St. Benedict (c.480-c.547), as the latter died when Gregory (540-604) was but a young child. But he lived and associated with St. Benedicts disciples and was informed by them, as faithful eyewitnesses, of the life and deeds of this great man. Those who contributed to the facts recorded by Pope Gregory are the following: Abbot Constantine, first successor of St. Benedict in the monastery of Monte Cassino; Abbot Valentinian, who directed the monastery of the Lateran; Simplicius, third Abbot of Monte Cassino; and finally, Honoratus, who was Abbot of Subiaco at the time of St. Gregory. These are the commanding authorities to which he refers in portraying to us the life of the Patriarch of monks.

The Downfall of the Roman Empire

With regard to Church and State, never was the condition of Europe so sad and deplorable as at the time when St. Benedict was born. A total downfall of existing conditions had taken place; all bonds of order seemed dissolved, and civil laws and authorities done away with. More than ever was the Church infected with heresy and schism. The greater number of the European nations adopted the heresies of Arius, Nestorius and Eutyches. Some countries, such as Germany and England, were still in the darkness of paganism. The Roman empire, that gigantic union of two hundred million people under Emperor Augustus, was overthrown amid the invasions of the barbarous hordes from the North, who, penetrating into the heart of Europe, devastated the entire country and, spreading to the South and West, brought about that immense movement known in history as the migration of nations. In Italy alone, the Ostrogoths had founded a kingdom which was effectually governed by several kings, such as Theodoric the Great, Totila and others.

A Prey to Heresy and Barbarism

These unsteady conditions and ever-changing circumstances were most detrimental to the Church. The new barbarous tribes, it is true, embraced Christianity; nevertheless, they were to a great extent given to the Arian heresy, and thus the countries in which the first disciples of Christ had preached the Gospel became a prey to heresy and barbarism. It was, therefore, necessary that the world should be reconquered for Christ. And this enormous work of conversion was in great measure effected by St. Benedict, through the organization of his renowned Order of monks in the West. This holy Order God had chosen for His Church, in establishing the Christian world upon the ruins of the dilapidated Roman empire and in instructing and civilizing the new tribes unto Christ and Christian society. It is wonderful, says a historian, how Divine Providence has manifested its care for the Church by calling St. Benedict for this great work. Because at the very time when all Italy, France, Spain and the northern coast of Africa were in the possession of the Goths and Vandals, and almost the entire East was infected with heresy, in this frightful darkness, so bright a light shone forth from St. Benedict and his Order, that the whole world was thereby illumined.

St. Benedict of Noble Family

St. Benedict was born in the year 480, at Nursia, a city in southern Italy. He was descended from the Anicians, a noble Roman family which numbered among its members most renowned men: senators, generals and even saints. His fathers name was Eupropius, his mothers Abundantia; his pious and holy twin sister, whom he cherished with tender affection his life long, was called Scholastica. Regarding the early years of St. Benedict and St. Scholastica little is known, but we rejoice in the possession of a beautiful vision of Anne Catherine Emmerich, which contains a very touching description of the childhood years of the twin brother and sister. For the edification and instruction of the reader, it is inserted here.

The Vision of Anne Catherine Emmerich

Through the relics of St. Scholastica, I saw many scenes in her life and that of St. Benedict. I saw their paternal home in a great city, not far from Rome. It was not built entirely in the Roman style. Before it was a paved courtyard whose low wall was surmounted by a red latticework, and behind lay another court with a garden and a fountain. In the garden was a beautiful summer-house overrun with vines, and here I saw Benedict and his little sister Scholastica playing as loving, innocent children are wont to amuse themselves. The flat ceiling of the summer-house was painted all over with figures, which at first I thought sculptured, so clearly were their outlines defined.

The brother and sister were very fond of each other and so nearly of the same age that I thought them twins. The birds flew in familiarly at the windows with flowers and twigs in their beaks and sat looking intently at the children, who were playing with flowers and leaves, planting sticks and making gardens. I saw them writing and cutting all sorts of figures out of colored stuffs. Occasion ally their nurse came to look after them.

Their parents seemed to be people of wealth, who had much business on hand, for I saw about twenty persons employed in the house; but they did not seem to trouble themselves about their children. The father was a large, powerful man, dressed in the Roman style; he took his meals with his wife and some other members of the family in the lower part of the house, while the children lived entirely upstairs in separate apartments. Ben edict had for preceptor an old ecclesiastic with whom he stayed almost all the time, and Scholastica had a nurse near whom she slept. The brother and sister were not often allowed to be alone together, but whenever they could steal off for a while, they were very gleeful and happy. I saw Scholastica by her nurses side, learning some kind of work. In the room adjoining that in which she slept stood a table on which lay in baskets the material for her work, a variety of colored stuff, from which she cut figures of birds, flowers, etc., to be sewed on other larger pieces. When finished they looked as if carved on the groundwork.

Next page