Marc Hamer

SEED TO DUST

A Gardeners Story

Contents

About the Author

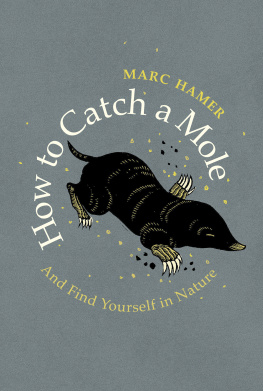

MARC HAMER lived in the North of England before moving to Wales. After spending a period homeless, then working on the railway, he returned to education and studied fine art in Manchester and Stoke-on-Trent. His previous book is A Life in Nature: Or How to Catch a Mole which was longlisted for the Wainwright Prize.

Also by Marc Hamer

A Life in Nature: Or How to Catch a Mole

This book, like my life, is for Peggy.

Prologue

The swifts have left the bell tower and are on their way to Africa.

As an exercise in holding my attention on a single thing, my minds eye held the pattern that an individual made as a wandering pencil line across the sky. Another swift crossed the line, and then more, returning as all things do to the creative chaos from which they came. In the warp and weft of the strands they drew, I saw the structure of this book cycles around cycles, lives lived, relationships made and lost, from seed to dust.

Written in a tradition as old as storytelling itself, in essence what is here is truth, although in fact it is often not. What follows is drawn from memory and, just like any other drawing, any other memory, perspectives are distorted, time is contracted and the sun shines in the imagination where in reality there was only shade.

Villedieu les Poles, Northern France

January

White

Fallen leaves curl as if to fold their fingers in for warmth. Hot breath steams from the rudely open gobs of pipes on the outside walls of houses, while inside hungry, roaring flames or coiled electric elements nested deep in boilers keep the people safe, away from natures icy teeth. The air outside is densely filled with crystals that turn it into mist so thick I cannot see the nearby church spire through the leafless trees. All is still. Still and silent. The celebrations of Christmas and New Year seem long gone; the people who have jobs have returned to them, but I have not. Ill have this month for myself, as gardeners often do. January is a time for looking at seed catalogues and dreaming of what could be, if I moved this and dug up that, and planted those over there. The garden floating in my mind shifts like a Mark Rothko painting as I slide a block of colour here and merge two colours there, make a path to break things up, plant a scribbly hedge to build a magnetic corner space. All gardeners have fantasy gardens, and many of them are painters. I no longer paint: painting requires lots of equipment and a permanent workspace to keep it all. I write instead. I can do that anywhere.

The world, outside my house and in, seems peaceful. Although the world of men is rarely peaceful, my own small bounded world relaxes. In the Rookwood where I live, everything looks black and white. The jackdaws, slow and calm, huddle by the chimneys or jab half-heartedly at the frozen earth, the lucky ones pull listless cold worms from the ground or squirming arthropods. The trees do not sway, but point their limbs up and around and wait. The sparrows are quiet, too, still flitting from shrub to shrub but not saying much, and I am watching through my window as if waiting, but not waiting.

The cold is busy doing vital work, sneaking between the grains of earth, lowering the temperature of molecules of water so they slow and cease their movement then expand and push the grains apart, so when the thaw arrives, the clods of soil on the surface crumble. It creeps into the cells of beasts and mingles with their being, as they breathe out warmer air that condenses into steam. It seeps into poor houses and chills the feet and clothes of warm children dressing for school; clings onto the homeless as they shelter in their doorways overnight; and builds crystals on the edges of tawny, dead hydrangea petals, kissing the kale and sprouts and winter cabbages to make them sweet and tasty. It wraps thickly around the apple trees to send them into a sleep so deep that, when they wake, they burst with energetic fruits.

Im indoors and resting like my cat, who jumps onto my lap as soon as I sit down. A tortoiseshell called Mimi, who loves me like I love her, selfishly and greedily wanting my warmth, as I want her adoration and luxury. She looks into my face; she has splotches in her eyes, brown spatters against the amber, like freckles. Ive always been a sucker for freckles. Im torn between the book Im reading and watching the outside go by. Im reading, yet again, W. G. Sebalds Rings of Saturn and feeling snug and blanketed as I follow his meandering journey, which seems to me to come from nowhere and end up nowhere. I like a story that feels real like that.

Beginnings

A new year, a new calendar, a new diary. The indoor world doesnt feel so new; the same dust blows under my desk, the same ache in my left knee. The only thing thats new is my diary, leaning next to the old one, which still has a few entries I need to copy across. Had the old diary more pages, it would carry on being used and would do its job as well. It neednt end quite where it does.

In the distant past, our ancestors chose to begin the new year at midwinter, when the feast of harvest was long gone and there were no available crops in the field, while they watched for the spring to come and show some mercy. Perhaps, in more primitive times, people may have feared that winter was the end of a world that was fading away into permanent cold and darkness. Somebody wrapped warmly in skins perhaps became aware that the falling sun had changed its behaviour and was now climbing higher each day. Look, guys, its going to be okay! They watched it all go by and saw that everything in the world was always changing, all at different rates. Theres always something new appearing on the scene, coming round the corner. Zoom in too close and things appear to pop into existence and then pop out again. Move back and you can see it all spins round and everything is just background whorl. When Im feeling sad for any reason, Ive learned to take a step back, but our senses can only perceive so much; there is so much more they cannot see, and we can never know what exists outside our narrow frame.

After the longest night of the year around 22 December, when the sun slowly starts to return, it seems a good time to begin a new cycle. So we mark the rim of the wheel that infinitely turns; we make it halfway through the darkness as it fades into the light, and we say, This is where the circle starts. That day was the very first date in the very first calendar and the start of our culture. I wonder what human life on this planet might have been like, had we been unafraid of the dark and felt no need to count the days and the seasons; if we had never developed a system of numbers, like some Amazonian tribes and children who do not recognise the difference between three sweets and four.

Next page