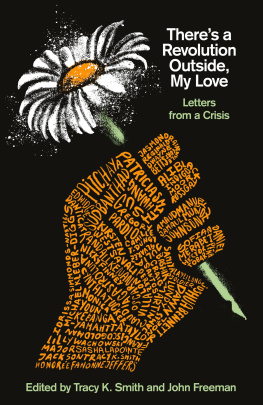

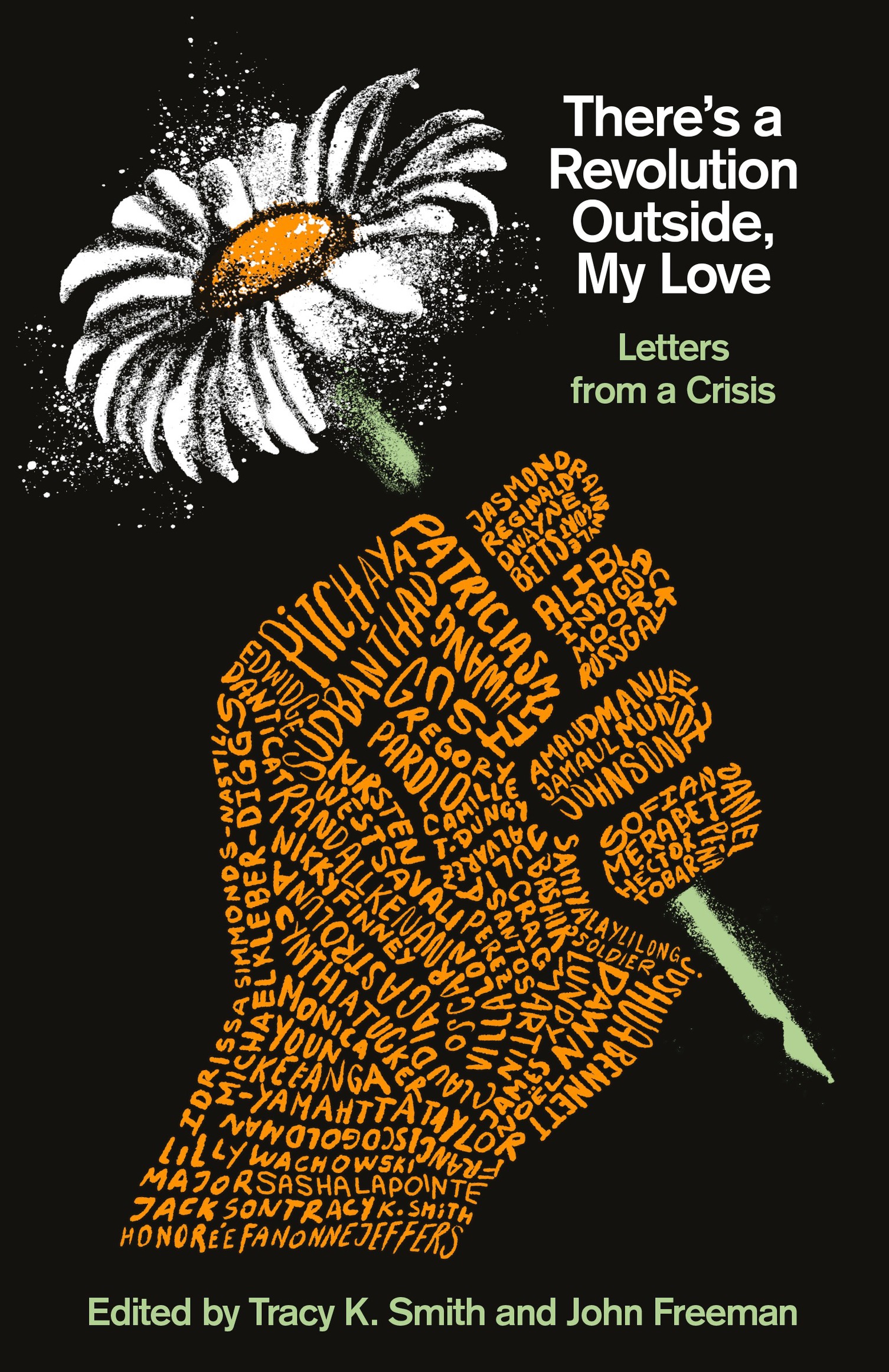

Theres a Revolution Outside, My Love

Edited by Tracy K. Smith and John Freeman

Tracy K. Smith is the author of four books of poetry, including Life on Mars, winner of the Pulitzer Prize. Such Color: New and Selected Poems will be published in October 2021. She is also the editor of an anthology, American Journal: Fifty Poems for Our Time, and co-translator (with Changtai Bi) of My Name Will Grow Wide Like a Tree: Selected Poems by Yi Lei. Smiths memoir, Ordinary Light, was named a finalist for the National Book Award. From 2017 to 2019, Smith served two terms as the twenty-second Poet Laureate of the United States. She is currently a chancellor of the Academy of American Poets.

John Freeman is the founder of Freemans, the literary annual of new writing, and an executive editor at Alfred A. Knopf. The author of five books, including The Park and Dictionary of the Undoing, he has edited several other anthologies, including Tales of Two Americas, a book about inequality in America, and Tales of Two Planets, which examines the climate crisis globally. He teaches at New York University.

A VINTAGE BOOKS ORIGINAL, MAY 2021

Copyright 2021 by John Freeman and Tracy K. Smith

Preface copyright 2021 by Tracy K. Smith

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

Vintage and colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

The Red Wheelbarrow by William Carlos Williams, from The Collected Poems: Volume I, 19091939, copyright 1938 by New Directions Publishing Corp. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.

The Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file at the Library of Congress.

Vintage Books Trade Paperback ISBN9780593314692

Ebook ISBN9780593314708

Cover design and illustration by Max Rompo

www.vintagebooks.com

ep_prh_5.7.0_c0_r1

Contents

Preface by Tracy K. Smith

I spent the summer of 2020 like many of my friends and loved ones near and far: worried, bothered, and gripped by uncertainty. How long would the pandemic last? Who would survive? How long would violence against unarmed Black citizens continue to claim lives? How far off were things like justice, safety, accountability, equity, truth? Were we as a nation heading toward them or in some other direction?

During the summer of 2020, held in place at home alongside everyone else in America, I experienced the feeling of having come to a crossroads. With it came the sensation of being pulled simultaneously forward and backward in time. We could move ahead into reconciliation and redress, or we could allow ourselves to be yanked back by our national denial of the ways that systemic racism impoverishes us all, no matter who we are.

It was this sense of a standstill, and the dire stakes of the decision at hand, that put me in mind of another iconic summer in American history: Freedom Summer of 1964, when northern and predominantly white college students traveled to Mississippi to participate in the effort to register Black voters.

A young John Lewis, at that time the chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), organized and conceived the endeavor with the dual aims of enfranchising Black citizens (at the time, fewer than 7 percent of Mississippis Blacks were registered to vote) and educating northern whites as to the violent realities of southern racism. Among the other famous names associated with Freedom Summer are those of three volunteers slain by the Ku Klux Klan for their participation in the campaign: James Chaney, a Black civil rights worker from Meridian, Mississippi; Andrew Goodman, a New York City social worker and civil rights activist; and Michael Mickey Schwerner, a New Yorkbased organizer for the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). These martyrs, and the nearly one thousand Black and white volunteers serving beside them, endured violence at the hands of racist mobs and Mississippi law enforcement agents. They witnessed a state-sanctioned campaign of terror that included beatings of volunteers, burning and firebombing of Black homes and churches, and the murder of local Blacks who supported the civil rights movement.

As bold and unapologetic as Mississippis violent campaign against Black voter registration was, there was also the widespread attempt to discredit the murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner as a hoax, a rumor perpetuated by a group of meddlesome outside agitators. A white Mississippian in a TV news clip repeated this theory, adding for good measure, But if theyre dead, its because they asked for it. It is one of the great paradoxes of racismone playing out in the summer of 2020 in acts of violence against protestersthat its agents are equally brazen in their aggression (driving into crowds, teargassing peacefully assembled protesters, kneeling on a mans neck for nearly nine minutes as he pleads for his life) and adamant in their insistence to be seen as the aggrieved (victims of lawless rioters, keepers of law and order, targets of insubordination or plausible threat). In the weeks leading up to the discovery of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerners remains, eight Black bodies were recovered from Mississippi rivers and swamps, onethat of fourteen-year-old Herbert Oarsbywearing a CORE T-shirt. Perhaps the current analogy would be the deaths, at the hands of police, of Rayshard Brooks in Atlanta and David McAtee in Louisville, which occurred not just during but some might argue precisely because of a summer of calls for police accountability.

If measured by voter registrations alone, Freedom Summer failed. But the campaign raised national awareness of the organized and authorized nature of racial terror and oppression in Mississippi. And it served as an intensely compelling argument for the aims and the tactics of the civil rights movement. White northerners, witnessing coverage of these events on televised news, grew more sympathetic to the civil rights movementperhaps because the young white activists volunteering in the foreign land of Mississippi allowed them to see their own childrenin real or proxy formas the protagonists in the effort for civil rights.

For the volunteers themselves, the summer was galvanizing not only because they saw themselves as agents of justice in the face of real evil, but because it cast them in positions of disenfranchisement that paralleled those of everyday Blacks in Mississippi, people who were often the targets of white mobs, whose homes were routinely shot at and firebombed by segregationists determined to keep the Black vote from interfering with the rule of white supremacy. In other words, for a few months during 1964, white participants were stripped of some of the privilege of their whiteness. The abstract concepts of civil rights and racial justice were transformed into actual lived experience and concrete embodied knowledge. These students went home eager to act upon their new knowledge, and to further the work of the civil rights movement from their communities and their college campuses.

Perhaps this is all well enough remembered. Perhaps there are also those who recall that the campus Free Speech Movement was one legacy of Freedom Summer, initiated by college studentsamong them Mario Savio at UC Berkeleywho returned home from Mississippi with the desire to keep organizing toward the goal of civil rights. In order to do so, they had to overcome institutional roadblocks to campus prohibitions on political organizing and demonstration.