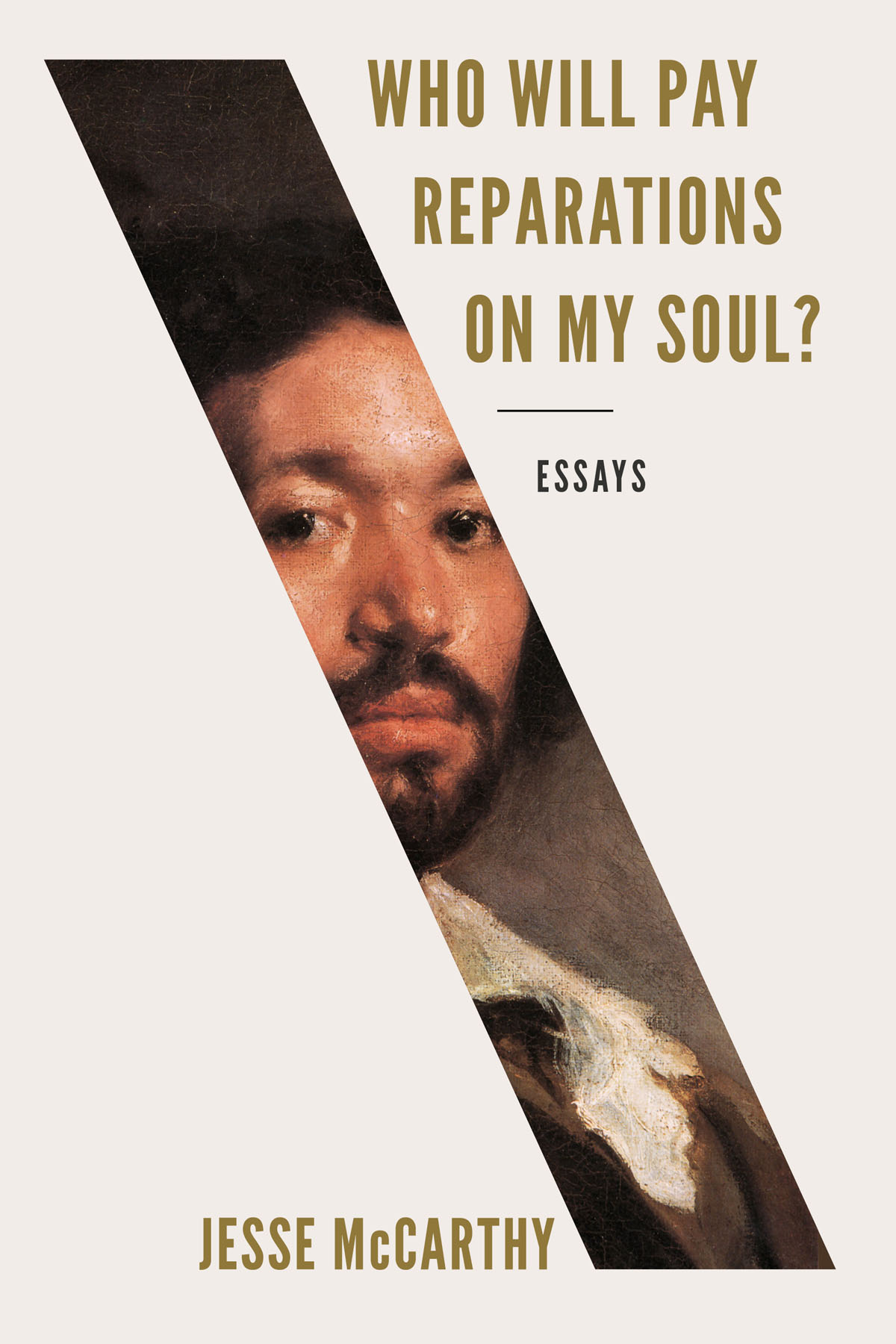

Jesse McCarthy - Who Will Pay Reparations on My Soul?

Here you can read online Jesse McCarthy - Who Will Pay Reparations on My Soul? full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, publisher: Liveright, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Who Will Pay Reparations on My Soul?

- Author:

- Publisher:Liveright

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Who Will Pay Reparations on My Soul?: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Who Will Pay Reparations on My Soul?" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Who Will Pay Reparations on My Soul? — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Who Will Pay Reparations on My Soul?" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Who Will Pay Reparations on My Soul?

ESSAYS

ESSAYS

Jesse McCarthy

They gave us

Pieces of silver and pieces of gold

Tell me,

Wholl pay reparations on my soul?

G IL S COTT -H ERON

This book is dedicated with deepest love to Raymond Lewis

To all my family & dear friends

Contents

P RIDE IN CULTURE and rooted history have always been important to our struggles. Historically, W. E. B. Du Bois and others fought to have the word Negro capitalized for this very reason. In that case, the Negro became a demonym specifically denoting US racial blackness. The word Negro, and the campaign to raise its profile, reflects and will always be associated with the history of black Americans under the racial regime of Jim Crow. The landmark achievements of the civil rights movement spearheaded by the student movements (SNCC, CORE, et al.) and the leadership of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference under Martin Luther King Jr. defeated the legal standing of Jim Crow with the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. A new era, it was felt, demanded a new vocabulary and initiated debates over whether African American, Afro-American, or simply black should be the preferred term going forward. The impact of the Black Power and Black Arts Movements on these debates was considerable and consensus moved in the direction of adopting black, sometimes capitalized and sometimes not, though it is worth noting that even Kwame Ture and Charles Hamilton in Black Power (1967), one of the seminal articulations of the politics of that moment, still have black in lowercase. Capitalizing Black belongs to a specific cultural momentmostly concentrated in the late seventies and early eighties. Angela Davis uses Black in Women, Race, and Class (1981), as does Audre Lorde in Sister Outsider (1984). Mainstream usage of the capitalized form did not endure for very long. Angela Davis, for example, no longer uses it in Blues Legacies and Black Feminism (1998). The reasons for preferring a lowercase usage are various. Writers and scholars have differed over what the most pressing problems with a capitalized Black are, while nevertheless reaching a broad (though by no means unanimous) consensus that the costs outweigh the benefits. The complexity and breadth of the global African diaspora constitutes a major hurdle, and many debates over this usage have centered on a multitude of serious conceptual inconsistencies that arise when one attempts to claim a unified transhistorical ethnoculture under the rubric of Black. For those interested in a comprehensive and robust account of these problematics I recommend Tommie Shelbys We Who Are Dark: The Philosophical Foundations of Black Solidarity. While I encourage all who wish to capitalize to do so, you will find lowercase black throughout this text, except in cases where citation is a factor or if there is a locally pertinent exemption that makes capitalization necessary. While a robust historical consciousness of this issue seems to me essential, my own reasons for adopting a lowercase usage rest ultimately upon principles of tradecraft and precedent. I dont believe anyone has thought harder, taken more time, or weighed this question more carefully than Toni Morrison. She could have used a capitalized Black in her fiction, but she didnt. With the exception of the essay Rootedness: The Ancestor as Foundation, which belongs to the period discussed above, she also refused to use a capitalized Black in her essays. The fact that Morrison tentatively considered the usage, and then abandoned it, strongly supports rather than erodes the case against capitalization. Hortense Spillers and Nell Irvin Painter consistently use the lowercase, as does Tommie Shelby in the book cited above. I tend to agree philosophically with Fred Moten that what is most important about blackness is its dispersive and de-essentializing qualities, its resistance to the assumptive logics of possessive individualism and state power, a function that I would argue is better captured aesthetically by the lower case. Style guidelines are split at the moment as to whether to use a capitalized Black, and whether White, Brown, and perhaps other color demonyms should follow. The reasoning these norm-setting institutions have provided so far has not been clarifying or convincing. Despite all this, at the time of this writing, the style guidelines of the Associated Press and the New York Times have switched to recommending a capitalization of the word Black in the place of black whenever it is used as a racial ascription. Some feel that lowercasing black diminishes dignity. I would respectfully disagree. I believe the spirit of the people resides in the wordmajuscule or notas long as it is used wisely, considerately, and with care. If my reader fails to recognize themselves or to comprehend my usage in what follows, it will mean I have failed at some deeper level than any orthographic alteration could resolve.

JM

Art is not a matter of pointing up alternatives but rather of resisting, solely through artistic form, the course of the world, which continues to hold a pistol to the head of human beings.

T HEODOR A DORNO

W HAT DO PEOPLE OWE each other when debts accrued can never be repaid? What role does culture play in a society governed in such a way that its historical inequalities are continually reproduced and widened, and its moral insolvency perpetually renewed? What do those owed nevertheless owe to each other? What possible role can art or literature play under these conditions?

These were some of the questions that I was trying to answer for myself when I first started writing the essays collected here in 2014. That year saw Ferguson, Missouri, and then the entire country convulsed by a protest against the murder and brutalization of black citizens at the hands of police officers sworn to uphold the law and protect them. It was a time of revolt and an interrogation of the ongoing failure of the United States to live up to its stated beliefs and declared values when it came to applying those beliefs and values to the black people it has historically constructed itself over and against. Protests swelled under the banner of the Black Lives Matter movement. Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote his famous essay, The Case for Reparations. Reports were issued, reforms recommended, and new technologies of surveillance suggested as solutions.

Today, as I write these words, the nation is once again aflame. The cause is the murder and brutalization of black citizens at the hands of police officers. The revolt is more general than the last time; the virulence and sadism of its repression by the state more vicious. The essays in this book were all written in the interval between these uprisings, a strange time when everything and nothing seemed to change in America. When every hope and aspiration seemed for many tantalizingly for the first time within reach, and yet every disaster loomed larger than ever and more sinister. We took refuge in achievements. Our culture was making money like never before. Barack Obama was elected as the first black president of the United States. But all these breakthroughs came against the background of ecological disaster, the social disaster of incarceration and policing, the political disaster of our squabbling dysfunctional elites, the economic disaster of the derivative economy and its offshore looting of the real economy. America as the aspirational nation in progress that Obama tried to restore faith in seemed less and less tangible. In its place, America as a system, predatory upon its own citizens and upon the rest of the worlds resources, became increasingly obvious, its thuggish attitude embodied in Obamas successor.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Who Will Pay Reparations on My Soul?»

Look at similar books to Who Will Pay Reparations on My Soul?. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Who Will Pay Reparations on My Soul? and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.