Contents

Guide

About the Author

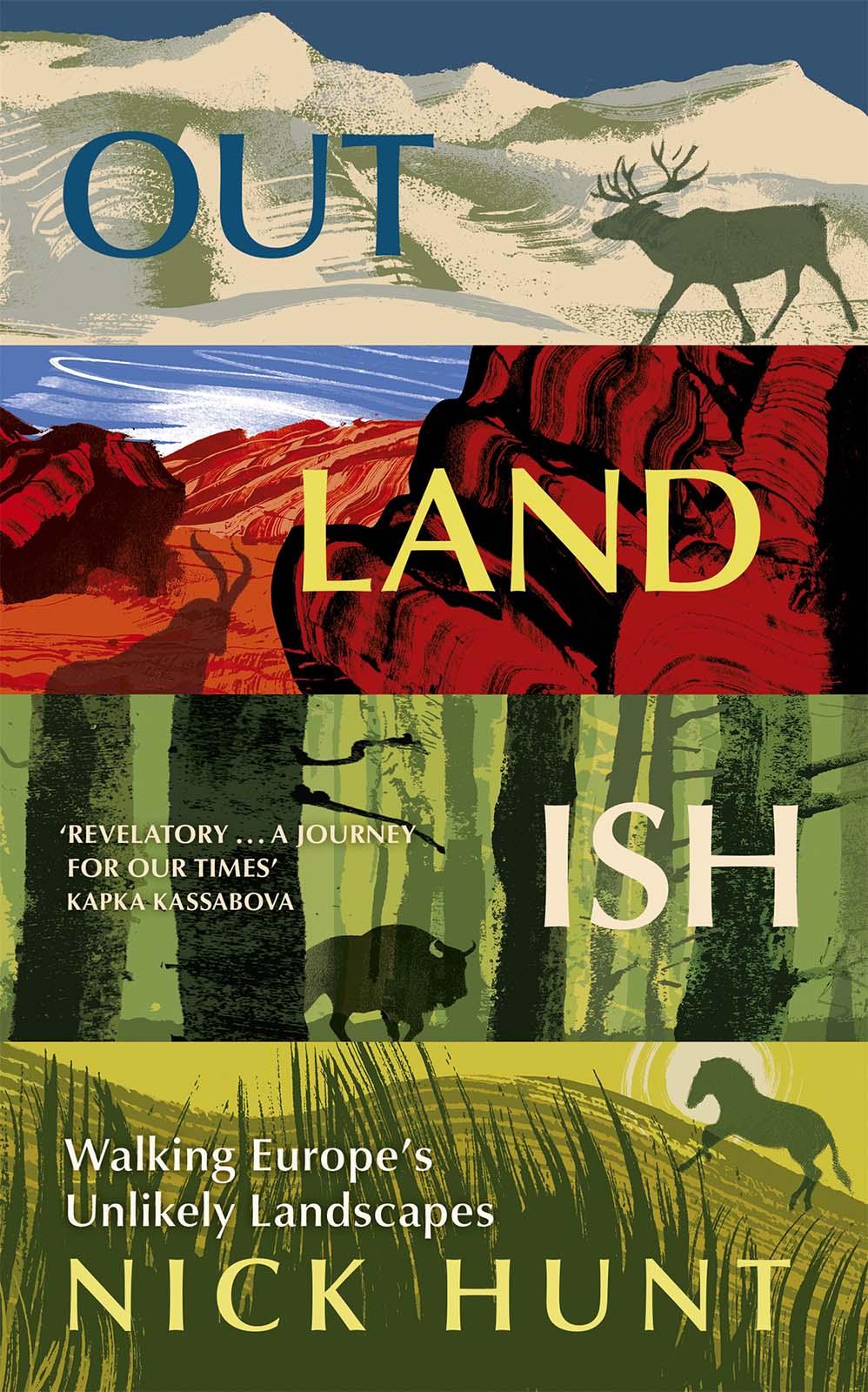

Nick Hunt has walked and written across much of Europe. His articles have appeared in The Economist, the Guardianand other publications, and he also works as a storyteller and co-editor for the Dark Mountain Project. His first book, Walking the Woods and the Water(Nicholas Brealey, 2014), was a finalist for the Stanford Dolman Travel Book of the Year. He currently lives in Bristol.

How to use this eBook

You can double tap images to increase their size. To return to the original view, just tap the cross in the top left-hand corner of the screen

Altogether elsewhere, vast

Herds of reindeer move across

Miles and miles of golden moss,

Silently and very fast.

W.H. Auden,

from The Fall of Rome

INTRODUCTION

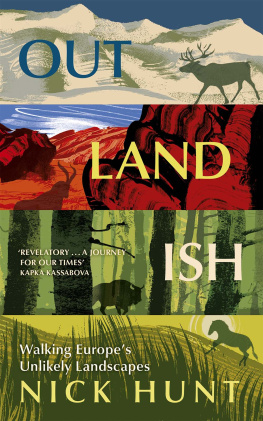

Outlands

The place that is sometimes called Englands only desert can be reached by a miniature railway line that runs to a nuclear power station on one of the largest expanses of shingle beach in Europe. Across the pebbled coastal plain a tiny, gleaming steam engine chugs bravely and ridiculously past weather-beaten huts and abandoned fishing boats, to deposit its passengers near the foot of a black lighthouse. The power station hums inland, too brutally large to understand. Ahead, the shingle foreshore lilts towards the sea. Sections of boardwalk lead visitors out across the stones, past rusted bits of winching gear and outcrops of sea kale; in summer, the pebblescape is red with poppies. Stepping off the wooden boards, stones crunch with every step. The shingle is composed of flint. If you bring your boots down hard, your footsteps might strike sparks.

The English desert of Dungeness draws a million people a year, pilgrims to its weirdness. Why go to the Sahara when you can visit Kent? The headland noses out from the south-east coast towards Boulogne-sur-Mer, thirty miles across the sea. It is out on a limb, on its way to nowhere.

We did not arrive by train, my partner Caroline and I, but by cycling eastwards along the sand-duned coast from Rye, inland through the town of Lydd, and then back towards the sea. Despite the cloudless, glaring sky, what felt like a gale-force wind tore against us all the way, dragging the breath from our lungs if we faced directly into it, so that we progressed like drunks, teetering and gasping. At times the wind was so intense that it almost forced us to retreat, or into the shelter of barriers raised against the sea, but soon there was no shelter left. Ahead lay only pebbles. The emptiness seemed immense and we became extremely small. Distances were hard to gauge, proportions misaligned.

We stayed for a week in Dungeness in one of the iconic huts it belonged to the family of a friend and spent our days walking the foreshore and our evenings watching the sun collapse in a wobbling orange ball, like a shot-down UFO. The sky was not the English sky but the sky of a greater continent, with a clearer quality of light. Our discoveries got stranger. Astonishingly for what looks, at first glance, like a desolate place, this headland provides a habitat for a third of Britains plant species, many of them rare; the ceaseless sifting of the sea sorts the pebbles into troughs and ridges that trap rainwater, creating small pockets of life. Sculptures of driftwood and scrap metal protrude along the shore, the creations of artists drawn here by the legacy of Derek Jarman, the avant-garde film director who coaxed a garden from the stones. And in one strange spot offshore, hidden pipes discharge hot water from the nuclear power station (actually two nuclear power stations, Dungeness A and Dungeness B) into patches dubbed the boils, where the warmer temperature attracts tiny sea creatures which, in turn, attract shoals of fish and wheeling seagulls. The waste water is apparently clean, but it is hard to overcome suspicions of mutant energies. A common description of this coast is post-apocalyptic.

One evening at sunset, with crimson light pouring over a scene of wind-whipped marram grass and the skeletons of boats, I experienced a moment of dislocation; suddenly I was not in England but in a North American wasteland, some time in an imagined future that felt dreamily familiar, surrounded by the flotsam and jetsam of a collapsed culture. The light; the rusted metal cables; the plants like deformed cabbages; the presence of the power stations with their mysterious blinking lights; the landscapes sheer outlandishness : it was briefly enough to jolt me free from time and place. Outlandish comes from the Old English tland , which means foreign country, and that was this deserts uncanny effect. It made my country foreign.