Table of Contents

For Claus Bech

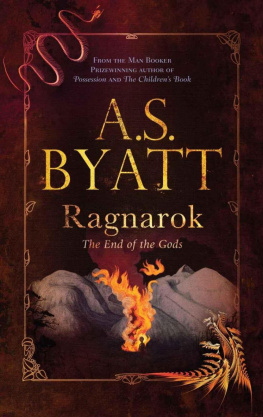

ACCLAIM FOR A. S. BYATTS

Elementals

[Byatts] prose has a lustrous yet exacting shimmer that answers to Keatss injunction that poetic language should surprise by a fine excess.

The Boston Globe

Energetic and magisterial... full of light and life.

The New York Times Book Review

Sparkling.... [Byatts] vivid prose leaps and pirouettes, shimmies and shivers.

The Wall Street Journal

Harnesses a brilliant new power.... Byatt has reached back to legend and fairy tale, elements of storytelling as basic and combustive as fire and ice.

Los Angeles Times Book Review

A collection of richly imagined stories etched in such vivid color, sensuousness, and language that they seem like art objects.... A delight.

Richmond Times-Dispatch

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to my Norwegian editor, Birgit Bjerck, for telling me about the one tree, and for information about PeerGynt. I am also grateful to David Perry for commissioning the ekphrastic tale about Velasquez. My husband, Peter, gave me a central idea about Jael, and Helen Langdon found several images of Jael that were most illuminating. I am, as always, grateful to Jenny Uglow, best of readers, for patience and inspiration. And also, as always, to Gill Marsden for order out of chaos.

The author and publishers are grateful for permission to reproduce the following illustrations:

Nmes crocodile: from The Crocodile of Nmes by W. Froehner, Paris, 1872; Sirne by Henri Matisse: from Ronsards Florilge des Amours. Collection Muse Matisse. Succession H. Matisse/DACS 1999; Faon de Venise goblet: Sothebys Picture Library; Jael and Sisera, School of Rembrandt: Kent County Council, from the Kent Master Collection; detail from Kitchen Scene with Christ in the Houseof Martha and Mary by Velzquez: National Gallery, London.

Crocodile Tears

Le Crocodile de Nmes

Crocodile Tears

Patches of time can be recalled under hypnosis. Not only suppressed terrors but those flickering frames of the continuum that, even at the time, seem certain to be forgotten, pleasantly doomed to nonentity. So they have sunk into our brains after all, are part of us. Patches of time is a mild metaphor, mixing time and space, mildly appropriate in art galleries, where time is difficult to deal with. How do you decide when to stop looking at something? It is not like a book, page after page, page after page, end. You give it your attention, or you dont. The Nimmos spent their Sundays in those art galleries that had the common sense to open on that dead day. Not the great state galleries, but little ones, where some bright object or image might be collected. They liked buying things, they liked simply looking, they were happily married and harmonious in their stares, on the whole. They engaged a patch of paint and abandoned it, usually simultaneously, they lingered in the same places, considering the same things. Some they remembered, some they forgot, some they carried away to keep.

That Sunday, they were in the Narrow House Gallery, which specialised in minor English art, drawings, prints of flowers, birds, angels, hand-screen landscapes and pop art posters. It was higgledy-piggledy, with real plums in the duff, Tony Nimmo used to say. The Gallery was in Bloomsbury, in what had been an eighteenth-century private house; it went up and up, with small rooms opening off a turning stair, which was also hung with stags and sunsets, garden gates, watering cans and silver lakes with swans on. They always had a good pub lunch on these Sundays. This one was a sunny Sunday in early May, a really sunny Sunday that narrowed the eyes in the light, that warmed the skin, even through glass. Patricia ate prawn salad; she was watching her figure. Tony ate a robust beef and ham platter with pickles and onions. Then he had brandy syllabub. And two pints of Special. He was a large man, with a bald crown above fine dark hair. His face was peacefully reddened, a pale poppy flush. They were in their middle fifties. Patricia wore a butter-yellow suit, nipped in at the waist, and a bronze silk scarf. Her hair was bronze too, fanning up and out. She had good big breasts and a generous bottom, solid and lively. On the top floor of the Narrow House, they had one of their rare disagreements.

The disagreement was about a work called TheWindbreak. It was small; about two feet long and one foot deep, framed in a deep, polished dark wooden frame, with brass nails. It was part collage, part oil painting. It was a seaside scene, an English seaside scene, with a blue-grey sea, flecked with dirty white, stretching to meet a pewter sky with livid oily blue patches. These took up the top two-thirds of the work. The beach had real sand scattered on a fawn surface, and tiny real shells and bits of seaside plastic reconstituted into tiny windmills and buckets and spades, sugar-pink, turquoise-blue, poster-red. Much of the left part of the beach was taken up with the windbreak. This was made up of painted cloth, in rainbow stripes, stretched on wooden pegs, representing stakes. There was also a coloured ball, Day-Glo orange with green stars on it. Patricias indifferent glance slid over this object; she had seen, in other patches of time, hundreds more or less like it; she moved on to contemplate a delicate six-inch-square dandelion clock on a cobalt-blue ground. Tony, however, was taken with The Windbreak. He went up to it, and peered into its glass box. He stood back and stared. He smiled. Patricia, when he called her, turned back from the dandelion, and saw him smiling.

I like this, said Tony. I really like this. It isnt much.

You cant like that, darling. Its banal.

No, its not. I can see how you might think it was. But its not. Its just simple and it reminds you of things, of whole of whole oh, of all those long days of doing nothing on beaches, you know, the mixture of misery and being out in the air and sort of free of being a child.

Banal, as I said.

Look at it, Pat. Its a perfectly good complete image of something important. And the colours are good all the natural things dismal, all the man-made things shining

Banal, banal. Patricia did not know why she was so irritable. It had been a good lunch. She could even, secretly, see what the memory-box would look like to her if she had liked it, as opposed to disliking it. Tony and the unknown artist shared an emotion, shared a response to the conventional images that evoked that emotion. She didnt, or if she did, it provoked opposition.

I like it, said Tony. Ill buy it, it can go in my study, in that space by the window.

Its a complete waste of money. Youll go off it in no time. I dont want a thing like that in the house. Look at the dreadful predictability of those colours.

Dont be so snooty. Its about the dreadful predictability of those colours. About sad English attempts to cheer up sad English landscapes.

They dont have to be sad. Not the English, not the colours, not the landscapes. Its a dreadful clich.

Clichs are moving.

I dont want it.

Next page