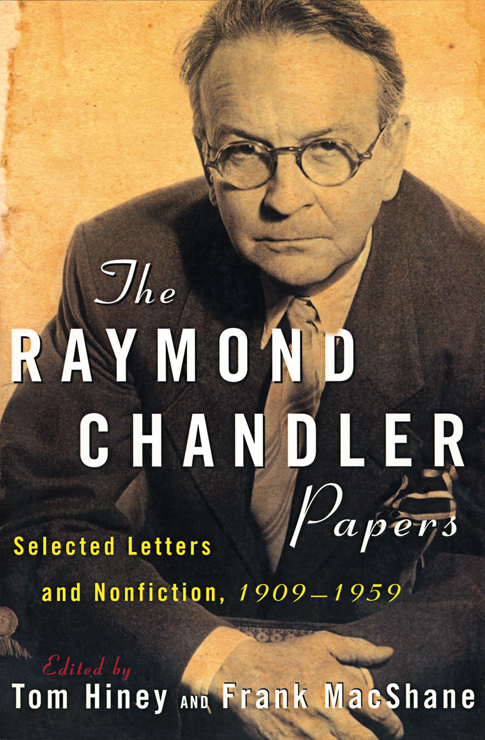

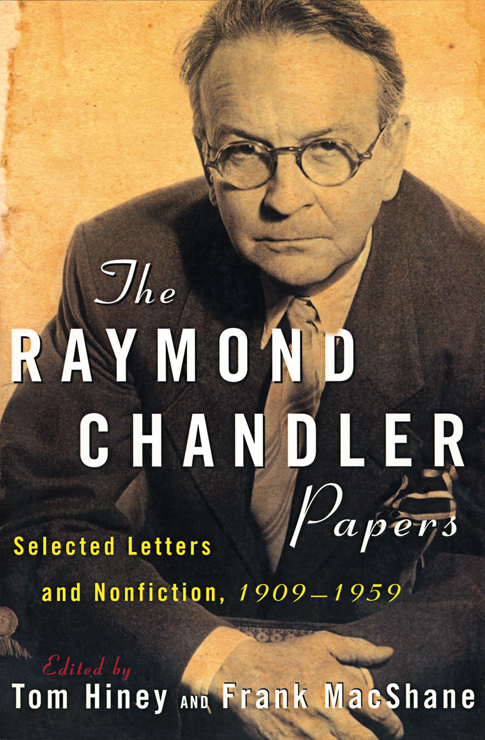

The Raymond Chandler Papers

The Raymond Chandler Papers

Selected Letters and Nonfiction, 19091959

RAYMOND CHANDLER

Edited by Tom Hiney and Frank MacShane

GROVE PRESS

New York

Contents copyright 2000 by the Estate of Raymond Chandler

Introduction copyright 2000 by Tom Hiney

Editorial arrangement copyright 2000 by Tom Hiney and Frank MacShane

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Any members of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or publishers who would like to obtain permission to include the work in an anthology, should send their inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003.

First published in the United Kingdom in 2000 by Hamish Hamilton Ltd., an imprint of the Penguin Group

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

FIRST GROVE PRESS EDITION

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Chandler, Raymond, 1888-1959.

The Raymond Chandler papers : selected letters and nonfiction, 19091959 / Raymond Chandler; edited by Tom Hiney and Frank MacShane.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 9780802194336

1. Chandler, Raymond, 1888-1959Correspondence. 2. Authors, American20th centuryCorrespondence. 3. Detective and mystery storiesAuthorship. I. Hiney, Tom, 1970II. MacShane, Frank. III. Title.

PS3505.H3224 Z48 2001

813.52dc21

[B]00-054314

Grove Press

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

02 03 04 05 0610 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Introduction

Act I (19091912)

Act II (19181943)

Act III (19441946)

Act IV (19461954)

Act V (19541959)

Index

Introduction

In a general way I am completely disgusted with the anthology racket. People who have given nothing to the world in the way of writing (and never will) presume to use other men's work at nominal, and by God I mean nominal, prices, for their own benefit and profit and to justify themselves as editors or critics or connoisseurs, in furtherance of which they write pukey little introductions and sit back with an indulgent smile and all nine pockets open.

Raymond Chandler to a publisher, 24 November 1946

Six years ago, I began work on a biography of Raymond Chandler. In so doing, it quickly became clear to me that the best source of material concerning the subject was that written by Chandler himself. This was in part by virtue of necessity. He had been a reclusive man, who had left no wife or children after his death in 1959. Nor were there any brothers or sisters; or even second cousins. He had been an only child and a childless man, and, clocking up over 100 addresses in the course of his life, rootless. The man Time magazine once described as the poet laureate of the loner appeared to be the genuine article. To know me in the flesh, he warned one correspondent, is to pass on to better things.

But while he may have been a recluse, Chandler was a compulsive letter-writer; and here lay many clues to the man behind Philip Marlowe. The surviving carbons of his letters are divided between a large collection at the Bodleian Library in Oxford and one at the University of California at Los Angeles. In those letters, of which thousands have survived, Chandler talks openly about life, writing and modern Californian society. Many of the letters included here were written late at night, spoken into a Dictaphone for his Mexican secretary Juanita Messick to type up in the morning. He was often drinking when he dictated them, and they serve as an unusually honest and freewheeling journey into the mind of a man who had seen a lot, read a lot, drunk a lot, thought a lot and steered perilously close to insanity in the process. He was as capable of fierce self-scrutiny as he was of antisocial virtuosity no one, I came to believe, could be more perceptive or informative about Chandler than Raymond Chandler himself.

The letters lie firmly at the heart of his written legacy, and there have already been two selections since his death in 1959: Raymond Chandler Speaking in 1962 and The Selected Letters of Raymond Chandler in 1981. I am indebted to both here, and particularly to the work of the late Professor Frank MacShane. Frank MacShane died in 1998. His work on Chandler in the 1970s and 1980s helped to convince the intellectual powers-that-were that Raymond Chandler was more than just a whodunit writer, but in fact a modern Californian shaman and an American literary treasure something his fans took for granted. MacShane's valiant work lives on in this selection and bases itself on his 1981 edition. I would also like to express my gratitude to the Chandler estate for having approached me to prepare this edition.

After spending a lot of time myself with the Chandler papers, I believe I have found some interesting new material. There is one main reason for this. The majority of Chandler's letters were to men and women he dealt with professionally: publishers, agents, lawyers. Most of these letters began with a matter of business at hand, and would then veer off into soliloquies concerning whatever fired Chandler's thoughts at that moment. Thus, for example, a letter to his accountant about tax matters might end up discussing cinema and chess (the latter described by Chandler as the greatest waste of human intelligence outside an advertising agency'). In the midst of an argument with his European agent about Italian translation rights, Chandler might offer an insight into General MacArthur's performance in World War II. And so on. Realizing how much still remained embedded within the avalanche of his business correspondence (which could easily fill two large wardrobes), I decided to resurvey his correspondence, from start to finish. I was rewarded, as I had hoped, with some classic lost Chandler moments. Readers familiar with the two earlier selections of Chandler's letters will therefore find plenty of new moments to enjoy here. In addition to that retrieved from existing papers (including never previously seen journalism) several new letters have come to light in the last ten years notably Chandler's two-year correspondence with a fan-turned-lover named Louise Loughner.

Raymond Chandler's letters and journalism are worth reading even by those not acquainted with his fiction. As the Washington Post's critic wrote in reviewing MacShane's selection in 1981, Chandler's letters are compulsively readable. At moments, in fact, they match the lucid heights of his fiction.

A potted sketch of Chandler's life will be useful for those not familiar with his story. For, in a century dominated by dislocation, Raymond Chandler had had a particularly unsettled background. Born in Chicago in 1888, he was the only child of an Irish-born mother and a Pennsylvania-born father. Both were lapsed Quakers, and his father was an alcoholic, whose job as a itinerant rail engineer meant Chandler saw little of him while growing up. Chandler and his mother spent his first years in a rented house in Chicago, then in a series of inexpensive hotel rooms, and increasingly with relatives in the prairies of Nebraska.

Next page