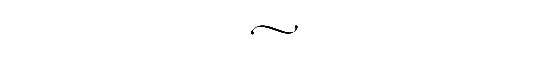

LIGHTS IN A DARK TOWN

MERIOL TREVOR

Lights In a Dark Town

A Story about

John Henry Newman

ILLUSTRATIONS BY

Hilda Offen

IGNATIUS PRESS SAN FRANCISCO

Copyright Meriol Trevor, 1964

Macmillan and Company Limited, London

Cover art:

The Cross, looking towards Watergate Street

by Louise Rayner Chester (18321924)

Wikimedia Commons Image

and

Portrait of John Henry Newman

by George Richmond (18091896)

Wikimedia Commons Image

Cover design by Davin Carlson

2017 Ignatius Press, San Francisco

All rights reserved

ISBN 978-1-58617-628-0 (PB)

ISBN 978-1-68149-761-7 (EB)

Library of Congress Control Number 2016941421

Printed in the United States of America

Contents

ONE

1849: English, but Strangers

DO YOU THINK winter goes on all the year round in Birmingham? Emmeline said to her mother as she stood by the window of their sitting-room, looking down into the dim, foggy street. Why, its March now, almost April! In Florence it would be spring, flowers coming out, the sun shining. I dont believe the sun shines in Englandit just gleams. It looks more like a shilling than the sun.

Mrs Erle was writing letters and said absently, Spring comes later in northern countries, dont forget.

She was a small, neat woman, looking pale and fragile in the black dress and cap which she wore in mourning for her husband, Emmelines father, who had died last year in France. Edward Erle was an Englishman who had gone to Italy to study painting; in Florence he had met and married Marianne Marney, who was half French and half Irish. They had been back to England once, about ten years ago when Emmeline was barely three, and she could not remember it. They had lived in Florence and in the south of France, and Edward Erle painted a little and read a great deal and spent the rest of his time talking to his many friends, of many different nations. He was never really well, always coughing and thin; he grew weaker and at last died, to the grief of his wife and only child.

Some months after his death, Mrs Erle received a letter from his elderly mother in England inviting her to bring Emmeline to live with her in Worcestershire. She was a little doubtful of this invitation, for Mrs Erle senior had been unfriendly to her in the past, but they were very short of money, and she felt it was right that Emmeline should get to know her English relations. So she accepted; they packed up all their things and made the long journey north. But when they reached Southampton, there was a letter at their hotel which informed them that old Mrs Erle had died suddenly, of heart failure.

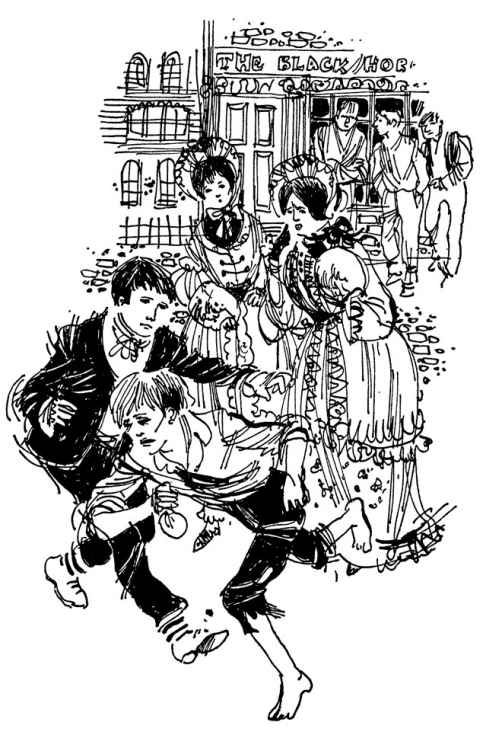

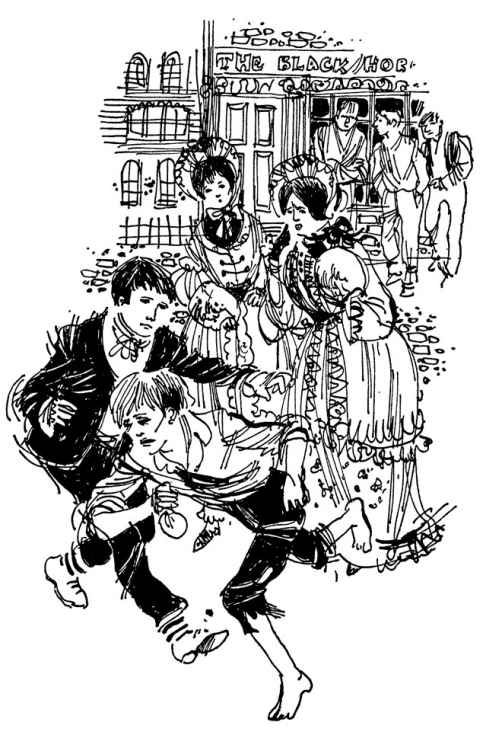

They went to the funeral, and there they met Edwards elder sister Louisa, who was married to a Birmingham manufacturer, Jacob Aldwich. They were both stout, formidable people, dressed all in black, and Mrs Aldwich was the taller and more impressive of the two. It was soon plain that she had had no hand in inviting her brothers widow and child to England and that she regarded their presence with disfavour. Old Mrs Erle had once changed her will, when she was angry with her son Edward, and had left all her money to her daughtersthere was another besides Louisa, who could not come to the funeral because she was in India. So there was nothing for Marianne Erle and Emmeline, and although it seemed to them that Jacob Aldwich was already rich in comparison with themselves, there was no suggestion of his making over any money to the poor relations from abroad. He and his wife contrived to mention their numerous family often enough to give the impression that great wealth was necessary to bring them up; some of the younger Aldwiches were present. Emmeline disliked them, especially a pasty-faced boy who put out his tongue at her and a beady-eyed girl who criticized her clothes quite audibly to the ladys maid.

Marianne Erle was too proud to make any complaint. She was determined to ask no help from people so plainly unwilling to offer it. But she was in a difficult position. She had not enough money to return to France, or to Florence, where her friends lived in the English colony. Besides, Italy in this year of 1849 was in a state of revolution.

Not knowing what else to do, she took rooms for herself and Emmeline in the nearest large town, which was Birmingham. They had the first floor to themselves of a tall, narrow lodging-house, at the end of a terrace. They had a sitting-room, which was also their dining-room, and two bedrooms, though Emmelines was really a dressing-room opening off her mothers. The landlady, Mrs Purdy, cooked the meals for her lodgers, and they were carried up on trays by her formidable servant Martha Sanders or by a skinny girl known as Lizzie, who seemed always to be climbing up and down the narrow stairs with jugs of water or buckets of coal.

Mrs Erle decided that, to earn her living, she would give French and music lessons. She was pleased to discover that there was a school next door, but surprised when she found that, as it was a boys school, her services were not required. However, Mrs Thorpe, the headmasters wife, condescended to give her some addresses and introductions, and she soon had almost more work than she could manage, for there were plenty of manufacturers wives who wished their daughters to learn what were considered the social accomplishments of ladies.

I wish I could do something to earn money, Emmeline often said. She said it now, coming away from the window and leaning on the back of her mothers chair.

My dear, you must learn your own lessons, said Mrs Erle. I am only afraid I am neglecting you in teaching these dull girls. I hope I am doing the right thing. She leaned sideways on the arm of her chair, looking at her daughter.

Emmeline was almost as tall as she was, and much stronger. She was not a pretty girl, for she had what her father had called a crusaders nose jutting from her thin face, and a wide mouth. But she had a high colour, and her eyes were both dark and bright. Her brown hair was very thick and reached well below her shoulders, but it was tied up in a tail, with black velvet ribbon. Emmeline was growing fast, and her bony arms and legs did not always dispose themselves tidily; she often knocked things over. Altogether she found it hard to fit herself into the right attitudes; she got fits of giggles at the wrong moments, shrieked when she was excited, and ran when she ought to have walked.

Perhaps because they were so different she and her mother got on well, though there were sometimes furious arguments about what Emmeline ought to do or to wearfurious on Emmelines part, exasperated on her mothers. Oh, how impossibly English you are! cried Mrs Erle sometimes. Do you want to turn into a real Miss?

Emmeline did not want to be a Miss. In earlier years she had wanted, very much, to be a naval captain. Unfortunately that career was not open to her sex, and so she had had to content herself with learning the rigging of every ship that sailed the sea, and the history of all Nelsons battles. Lately, however, the navy had paled somewhat before other enthusiasms, and Emmeline now thought she would be a great violinist. It was easy to imagine herself holding vast audiences under her spellwhere there were no audiences. She was rather a slapdash player in fact: hit or miss in this as in everything else. Her mother could not persuade her that she was better at the piano, as she was, because it was the violin which seemed to her just now the more romantic instrument. In a way this was lucky, as there was no piano in the lodgings.

Next page

![Blessed John Henry Newman - Blessed John Henry Newman Collection [26 Books]](/uploads/posts/book/371011/thumbs/blessed-john-henry-newman-blessed-john-henry.jpg)