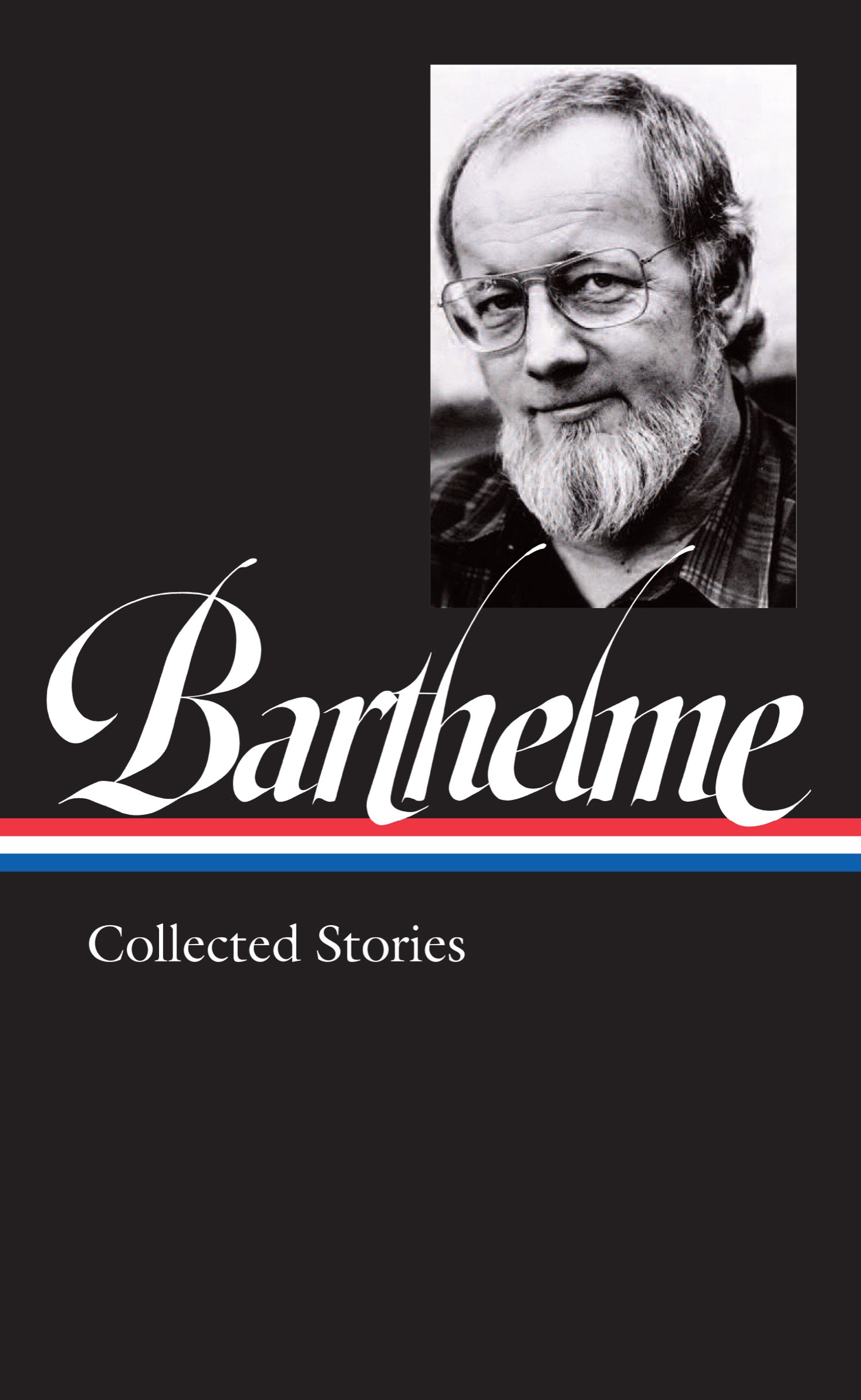

D ONALD B ARTHELME

COLLECTED STORIES

Come Back, Dr. Caligari

Unspeakable Practices, Unnatural Acts

City Life

Sadness

Amateurs

Great Days

FROM Sixty Stories

Overnight to Many Distant Cities

FROM Forty Stories

Uncollected Stories

Charles McGrath, editor

LIBRARY OF AMERICA E-BOOK CLASSICS

DONALD BARTHELME: COLLECTED STORIES

Volume compilation, notes, and chronology copyright 2021 by Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., New York, N.Y. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without the permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Published in the United States by Library of America.

Visit our website at www.loa.org.

Come Back, Dr. Caligari 1964 by Donald Barthelme. Unspeakable Practices, Unnatural Acts 1968 by Donald Barthelme. City Life 1970 by Donald Barthelme. Sadness 1972 by Donald Barthelme. Amateurs 1974 by Donald Barthelme. Great Days 1979 by Donald Barthelme. Overnight to Many Distant Cities 1983 by Donald Barthelme. Reprinted by arrangement with Counterpoint Press and the Estate of Donald Barthelme.

Sixty Stories 1981 by Donald Barthelme. Forty Stories 1987 by Donald Barthelme. Reprinted by arrangement with the Estate of Donald Barthelme.

Edwards, Amelia, A Man, Basil from Her Garden, and Tickets 1972, 1985, 1989 by Donald Barthelme. Reprinted by arrangement with Counterpoint Press.

Distributed to the trade in the United States by Penguin Random House Inc. and in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Ltd.

ISBN 9781598536843

eISBN 9781598536966

Contents

Introduction

BY CHARLES MCGRATH

D ONALD B ARTHELME was, by his own design, a hard writer to categorize. Even at the height of his fame, in the late 70s and early 80s, there were readers who just didnt get him, or suspected his work was a hoax or a joke they werent in on. At The New Yorker , where he was a regular contributor for decades, clerks in the library were expected to type up on index cards brief summaries of every article, fact or fiction, that appeared in the magazine. Barthelmes cards sometimes contained just one word: gibberish.

By most standards, many of his stories arent stories at all. They dont have plots, or even realistic, believable characters, and they touch on human emotion only indirectly. Barthelme loved arcane vocabulary, and called such pieces slumgullionsstews, that is. In the manner of visual artists like Duchamp and Rauschenberg, they incorporated all sorts of found materials: snippets from ad copy, old travel guides, textbooks, and instruction manuals, even other writers. The range of references and allusions in his stories is vast and encyclopedic: cheesy movies, nineteenth-century philosophers, opera, country-and-western, military history, art, architecture, soft-core pornography. For a while he even took to illustrating his work with engravings and pictures clipped from old books and magazines. He once wrote, only half-joking, that the most essential tool for genius today was rubber cement.

Many of the stories feel like riffs, jazzy improvisations on the way people speak: musician-talk, military lingo, art-jargon, academic highbrow. He was like his character Hokie Mokie, in the story The King of Jazz, of whom it is said, he can just knock a fella out, just the way he pronounces a word. What intonation on that boy! God almighty! Still other stories are retellings, or reimaginings, of older stories: Captain Blood, Bluebeard, the Hunchback of Notre Dame. Barthelmes version of Balzacs Eugnie Grandet includes a reference-book summary of the novel; a woodcut of Eugnie herself, holding a ball for some reason; and the word butter repeated ninety-seven times.

Barthelme was also fascinated by the trite and clichd, and sometimes incorporated snatches of writing that were deliberately clumsy and hackneyed, or else close to incomprehensible, like this one, from Paraguay, a story that also includes lengthy cribbings from obscure books:

Relational methods govern the layout of cities. Curiously, in some of the most successful projects the design has been swung upon small collections of rare animals spaced (on the lost-horse principle) on a lack of grid. Carefully calculated mixes: mambas, the black wrasse, the giselle. Electrolytic jelly exhibiting a capture ratio far in excess of standard is used to fix the animals in place.

One of his favorite devices was the list, an occasion for tossing in all sorts of rag-picked stuff just for its own sake: two ashtrays, ceramic, one dark brown and one dark brown with an orange blur at the lip; a tin frying pan; two-litre bottles of red wine; three-quarter-litre bottles of Black & White, aquavit, cognac, vodka, gin, Fad #6 sherry; a hollow-core door in birch veneer on black wrought-iron legs; a blanket, red-orange, with faint blue stripes; a red pillow and a blue pillow; a woven straw wastebasket; two glass jars for flowers; corkscrews and can openers; two plates and two cups, ceramic, dark brown; a yellow-and-purple poster; a Yugoslavian carved flute, wood, dark brown; and other items. Many stories of this assembled sort have an almost painterly quality; they remind you of Warhol sometimes, in their fascination with found objects and cultural detritus, and of Kurt Schwitters, in their collage-like layering of seemingly random elements.

But toward the end of his career Barthelme wrote stories so minimal and pared-down they were almost abstract, just alternating lines of overheard conversation preceded by a dash. Almost from the beginning, there were also stories that were monologues, stories that took the form of a catechism or a Q&A, stories that were out-and-out parodies, stories within stories, stories in the form of numbered lists, stories disguised as essays or interviews, and one story that consists of a single unfinished sentence seven pages long. Barthelme even wrote a few stories that seemed old-school, with real people and actual beginnings, middles, and ends. Late in his life he wrote a prize-winning childrens book, and though his gifts were not really novelistic, he nevertheless wrote four novelsextended, book-length narratives that paid a certain homage to the old conventions of the novel while also undermining them from within. If theres a constant in his career, its restlessness and a dread of seeming predictable.

Barthelme hated labels, but grudgingly accepted that post-modernist might not be too far off the mark, and biologically, at least, he really was one. His father, Donald, Sr., was an architect who ardently championed the work of Walter Gropius, Mies van der Rohe, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Le Corbusier. Modernism in the Barthelme household was practically a religion. The family lived in a modern house, designed by Don, Sr., so radical in its time and place, a Houston suburb in the 50s, that people used to park outside and gawk. The furniture was modern, and so were the paintings and the books. The father was impatient and imperious, and he and his namesake, his eldest child, were frequently at odds. But Barthelme nevertheless inherited from his father an unassailable conviction that there had been a revolution in art, and that there was no going back to the old ways.