THE GARDENS OF MARS

MADAGASCAR, AN ISLAND STORY

THE GARDENS OF MARS

MADAGASCAR, AN ISLAND STORY

JOHN GIMLETTE

AN APOLLO BOOK

www.headofzeus.com

This is an Apollo book, first published in the UK in 2021 by Head of Zeus Ltd

Copyright John Gimlette, 2021

The moral right of John Gimlette to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN (HB): 9781788544726

ISBN (E): 9781788544719

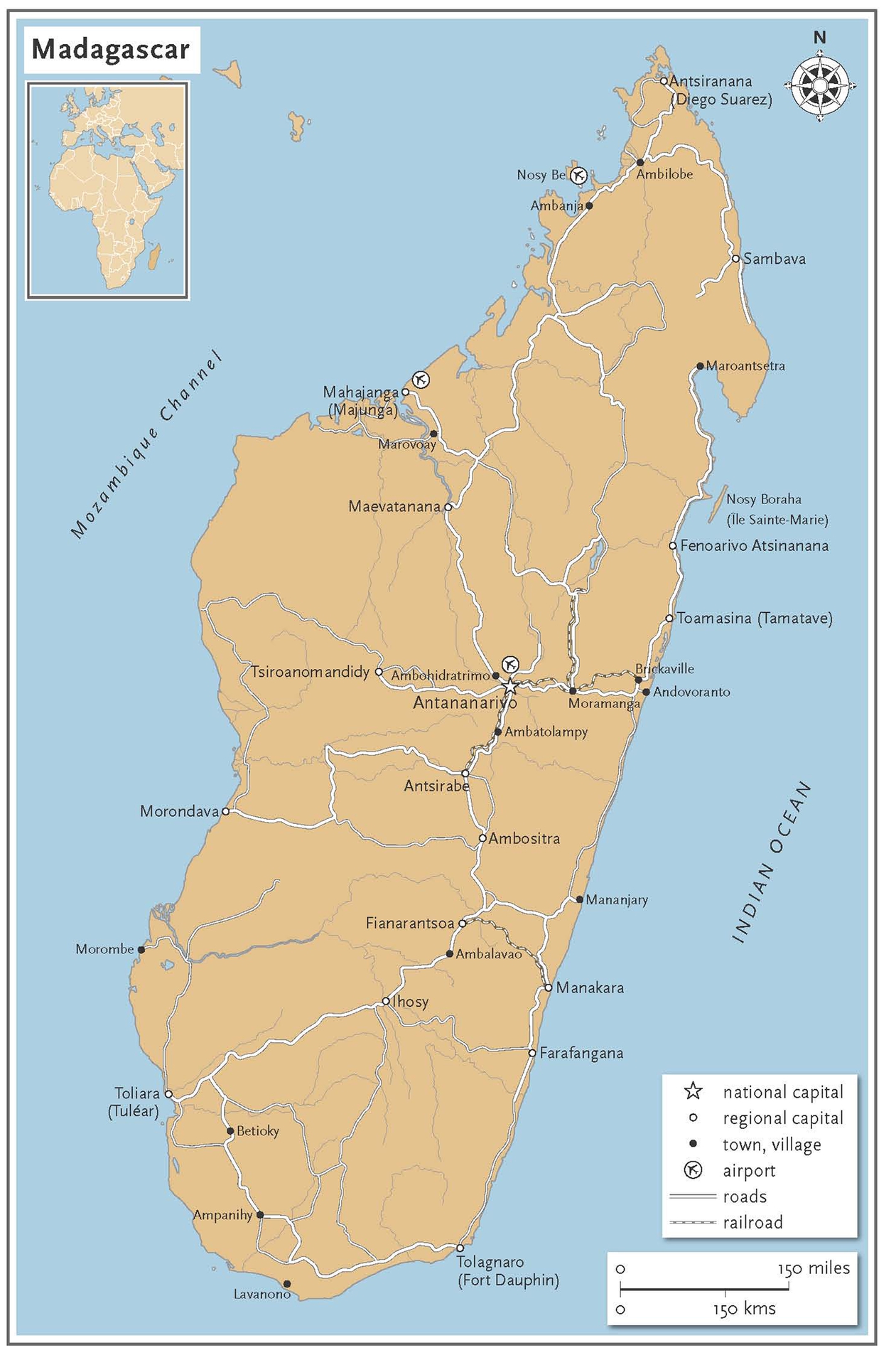

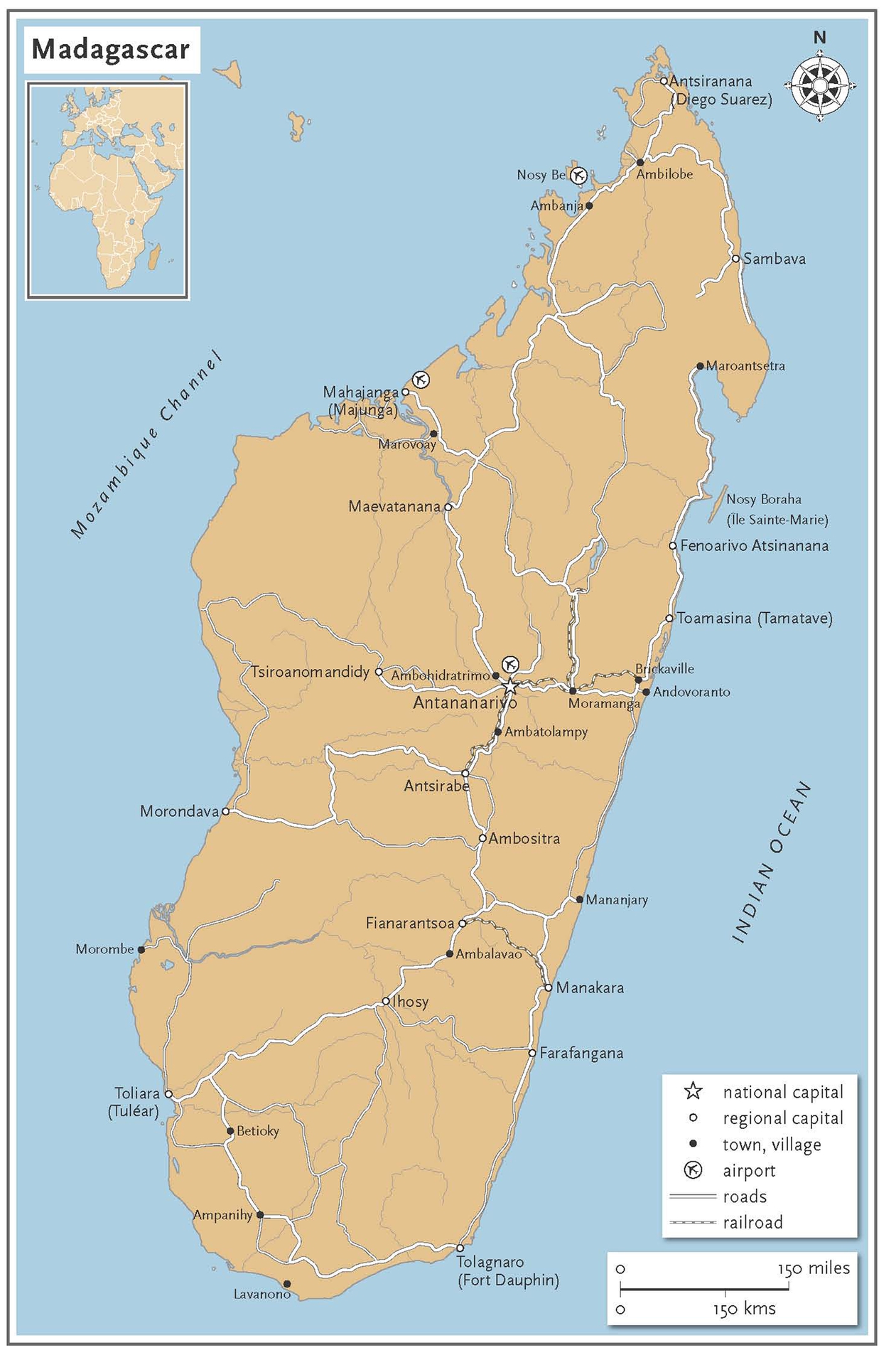

Maps by Jeff Edwards

Author Photo by Nick Moore

Head of Zeus Ltd

First Floor East

58 Hardwick Street

London EC1R 4RG

WWW . HEADOFZEUS . COM

To Mireille Rabenoro of the Malagasy human rights commission, la Commission Nationale Indpendante des Droits de lHomme (CNIDH), with thanks for her wise advice, and in recognition of her remarkable courage.

Contents

A LTHOUGH M ALAGASY IS A FINE and complex language, its devoid of plurals. This may look odd in the text, and takes some getting used to. Thus, for example, it doesnt matter whether you have one dahalo (bandit) or several hundred dahalo , it or they still look singular.

The language has, however, recently been shorn of accents. These sprouted in profusion during the French colonial period (18951960) but have since been lost. Except where I am quoting directly, Ive therefore used the modern spelling. Place names, however, are more complicated, because colonial names and new names often exist in tandem. Where the context is historical, Ive tended to use the older, colonial name simply to make things less confusing. The prime examples are Fort Dauphin (now Tolagnaro), le Sainte-Marie (Nosy Boraha), Tular (Toliara), Tamatave (Toamasina), Diego Suarez (Antsiranana), and Majunga (Mahajanga).

A few characters that appear in these pages have been renamed and their personalities disguised. Sometimes this was necessary for their safety or because they requested anonymity. But, at other times, I felt it was needed in order to protect their privacy (perhaps they had family problems or addiction issues). Ive tried to keep these changes to a minimum. However, it was necessary in the case of Rahanta Rakoto; Camille the Lebanese; my driver-guides, Faustin, Gaspar, Justin and Achille; Alix the Peace Corps volunteer, and Big Johnny. All are based on real characters, and I hope Ive done enough to give them the anonymity they want or need.

Finally, the journeys described in these pages didnt necessarily take place in the order in which theyre set out here. In some instances, Ive had to reorder them in order to convey Madagascars history in a chronological and therefore hopefully more coherent way.

Cherries refuse to grow on Madagascar.

A RTHUR S TRATTON

The Great Red Island , 1965

Madagascar is an island lying about 1,000 miles south of Socotra [its] gryphon birds are so huge and bulky that one of them can pounce on an elephant and carry it up to a great height in the air.

M ARCO P OLO

c. 1298

I shall not go back to Madagascar with its blood-red earth and its creeping shadows. The whole experience will remain isolated, an island as it were in my life as its scene was an island in the Indian Ocean. I shall not catch spies again or watch a firing squad, shoot crocodiles or be a Chef de Poste

R UPERT C ROFT -C OOKE

The Blood-Red Island , 1953

T HESE DAYS , NOT MUCH NEWS SEEPS OUT of the RepoblikanI Madagasikara (motto: Amour , Patrie , Progrs ). There are occasional articles about its ecology, usually cast in apocalyptic terms. Otherwise, the stories that filter through are often curiously picaresque: Captain Kidds treasure found, or Welsh adventurer to traverse Madagascar on foot for lemurs. During a lull in 2018, some papers even ran with the improbable tale of Hourcine Arfa, a French-Algerian boxer. Hed arrived on the island the previous year, to train the Presidential Guard. Finding himself in jail on unspecific charges, he managed to break out, and fled through the wilds before sailing away on a small open boat, a kwassa-kwassa . As a yarn, it was just too good to be true, and rapidly petered out.

Even the government news is tinged with oddity. There are around 200 political parties, and Malagasy elections are among the most expensive in the world, fought with elaborate cunning and millions of T-shirts. Recent presidents have included a disc jockey and a yoghurt magnate, and every now and then the hotels close and theres a military coup. Only a few years ago, Madagascar sprouted a rival capital city, which for seven months traded insults with Antananarivo. Standstills, it seems, have become a way of life.

The outside world hardly notices any of this. The truth is, few outsiders have any real idea where Madagascar is. Although its the fourth biggest island in the world (after Greenland, New Guinea and Borneo), its also strangely invisible. Search for it on the internet, and youre just as likely to find a cartoon. Malagasies may resent the caricatures and the talking lemurs, but thats often all Westerners see. What happens in Madagascar has little impact elsewhere, and with the Suez Canal its no longer on the way to anywhere else. An old diplomat once tried to explain to me how strategically inert the island is. If Madagascar were to disappear, he said, no one would notice.

Its always intrigued me, this unnoticed country. As a child I was brought up on Durrell and Attenborough, and was fascinated by the outlandish animals they caught. But the Malagasy people were harder to gauge. Did they tell jokes, and have an army? Was it too hot for clothes? And what were the spears for? As the years passed, Madagascar became ever more obscure, and yet I remained curious. What happens when 20 million people are left entirely to their own devices? Would it be like the Middle Ages? In 1992, shortly after university, I tried to get out there. However, by then, only Aeroflot were offering flights. Oddly, they could promise an outward leg but not the return. This was too curious even for me, and so another twelve years went by.

By that stage, I was writing travel pieces for the Daily Telegraph , and Madagascar came up. I was now married and so Jayne came with me. Its a mark of how little we knew that she travelled out four months pregnant. Even today, Madagascars medical services are skinny (with no neurosurgeons, for example, and few CT scanners), but, back then, they were skeletal. Happily, however, there were no antenatal adventures, and we were wafted around from lodge to lodge. Delightful creatures would come gambolling through the gardens, and I remember the fluffiest of towels and the whitest of beaches. Only occasionally were we aware of people, living under mud brick and reeds. Their jollity confused me, and I assumed their smiles said it all. We flew everywhere, and I returned home realising how little Id understood.