For Eden

Leaena meus

Regina fungorum meus

Cor meus

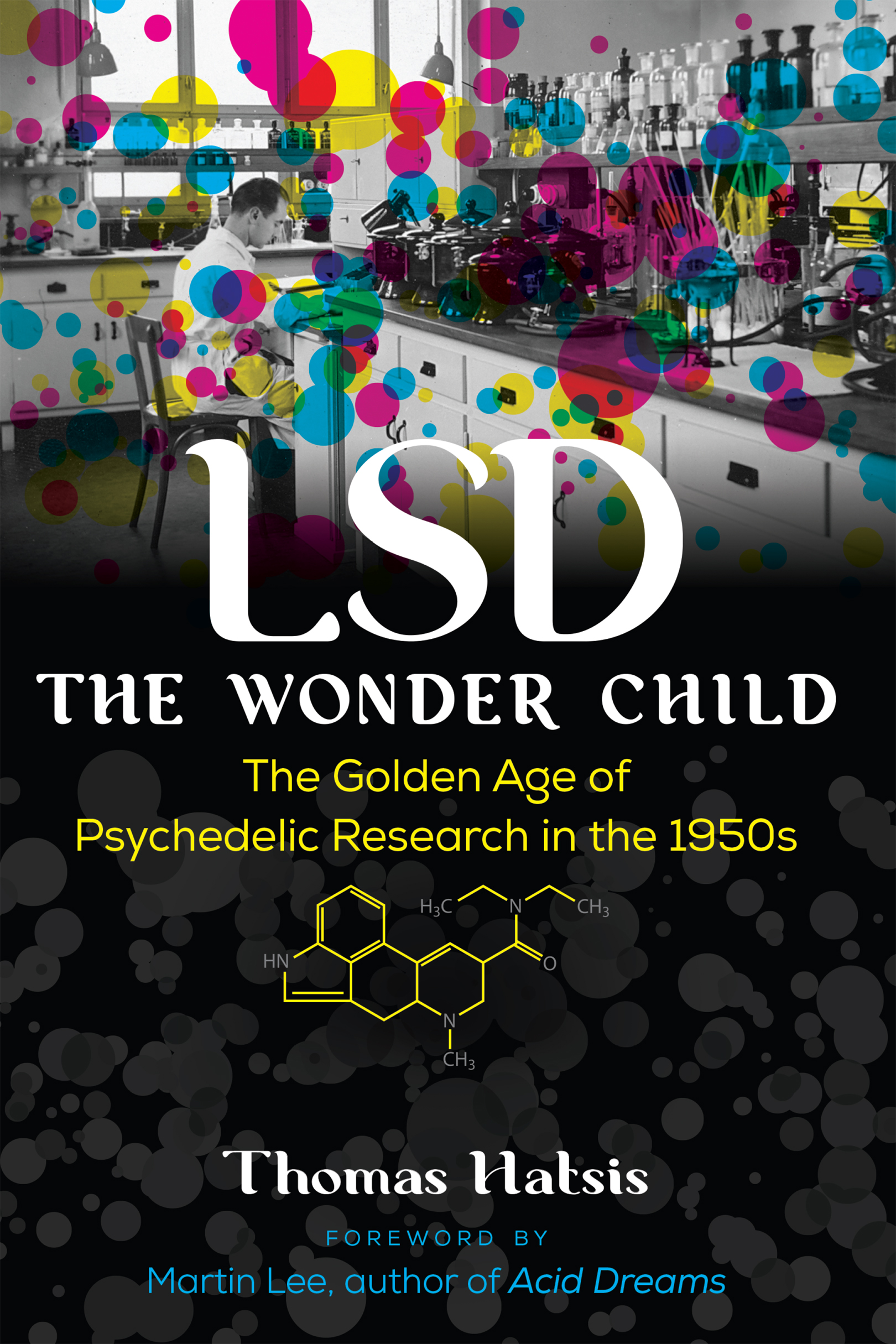

LSD

THE WONDER CHILD

An original synthesis of rare information, precious anecdotes, and scientific adventure stories. A masterful storyteller, Thomas Hatsis is our knowledgeable guide on this insightfully written history of pharmacologys most notorious chemical agent. From hopeful research into LSDs therapeutic potential and the hidden potential of the human mind to its sacramental use and the dark mind-control experiments of the CIA, Hatsis provides a page-turning historical perspective on the origins of psychedelic culture and how we got to where we are today in the psychedelic renaissance. Highly recommended!

DAVID JAY BROWN, AUTHOR OF THE NEW SCIENCE OF PSYCHEDELICS AND DREAMING WIDE AWAKE

A highly readable history of how psychedelics filtered through the wards of hospitals and prisons; the U.S. military and the MKUltra program; Huautla de Jimnez and Hollywood; university laboratories and the fields of parapsychology, mysticism, and literature; and into the clinics of psychiatrists, setting the stage for psychedelics spilling onto the streets of America in the 1960s.

MICHAEL JAMES WINKELMAN, PH.D., M.P.H., COEDITOR OF ADVANCES IN PSYCHEDELIC MEDICINE

Tom Hatsis brings this story to life with vivid characters, mystical and scientific intrigue, and exciting exploits in this colorful history of psychedelic adventures. His passion for the topic comes to life in this page-turner of a book.

ERIKA DYCK, PH.D., AUTHOR OF PSYCHEDELIC PSYCHIATRY: LSD FROM CLINIC TO CAMPUS

This wonderful book by Thomas Hastis is the most beautifully written, detailed, candid, personal, and informative text on the subject of Albert Hofmanns serendipitous stumbling. Get on the bus. Take that bike ride. Whatever. But make sure Toms book is in your backpack. Youll be hard pressed to find a better guide for your trip.

BEN SESSA, MBBS (M.D.), MRCPSYCH, PSYCHEDELIC THERAPIST AND CHIEF MEDICAL OFFICER AT AWAKN LIFE SCIENCES

Foreword

Martin A. Lee

If you think the psychedelic sixties were something special, check out the phantastic fifties. Theres no better place to start than this book by Tom Hatsis. It is the definitive romp through the hidden paisley underbelly of the Eisenhower years, an era otherwise known for its pre-dayglo blandness.

A full decade before counterculture figure and novelist Ken Kesey and psychologist Timothy Leary turned on, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and mescaline emerged as hot topics that catalyzed the nascent field of neuroscience. In the early 1950s, researchers drew attention to the similar molecular structures of LSD and serotonin, on the one hand, and mescaline and adrenaline, on the other, giving rise to novel theories about the biochemical basis of mental illness and the (supposed) madness-mimicking properties of these mind-altering compounds.

While brain scientists sleuthed for clues to unravel the riddle of schizophrenia, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the U.S. military secretly embraced hallucinogens as weapons that could revolutionize the cloak-and-dagger game to give America a strategic edge over its Cold War enemies. Odorless, colorless, tasteless, and super powerful, yet nonlethal, LSD, in particular, stoked the lurid imagination of U.S. spymasters, who employed the drug to disorient unwitting individuals and extract information from tightlipped targets. Army brass, for their part, were high on the possibility of disseminating a huge cloud of aerosol LSD (madness gas) as a battlefield tactic to incapacitate a large population without killing anyone.

Curiously, around the same time, a growing number of psychiatrists began touting LSD as a wonder drug for psychotherapy, an expeditious healing aid with an uncanny ability to quickly surface long-held sources of stress by dredging up whatever might have gotten stuck in the mental depths; thus, the word psychedelic, which literally translates as mind manifesting.

The psychedelic saga took an unexpected turn when the therapeutic potential of LSD was projected onto a broad social landscape. Leary and others trumpeted LSD as a cure-all for a sick society, a species-booster capable of propelling humankind to the next evolutionary level. The phrase stranger than fiction doesnt do justice to the real-world trajectory of LSD as it shapeshifted into a potent counterculture catalyst that dazzled the minds of artists, inventors, health professionals, and many more.

But how is it possible that the same compound could be used as both a mind-control weapon and a mind-expanding entheogen? How could it be both a psychochemical warfare agent and a profound healing modality?

With the benefit of hindsight, we can look back and see that every group that got involved with LSD during the phantastic fifties became very enthusiastic about the grandiose possibilities conjured by the drug. The brain scientists, the doctors, the spooks, and the generalseach had their own ideas about LSD and how it could be used to advance their specific agendas. But they also shared something in common: they all viewed it as the key to the big breakthrough. In each case, their encounter with psychedelics triggered an envisioning of new possibilities. Whether or not these different possibilities would ever be actualized is another matter, but the opening, the awakened sense of potential, was real and exciting.

In essence, LSD and other psychedelic drugs are best understood as potentiators of possibilityfor good or ill. Much depends on the context in which these compounds are consumed. The CIA ended up defining LSD as an anxiety-producing agentas if anxiety were embedded in the molecular structure of LSDbecause thats what Cold War espionage stiffs often experienced when they tripped on acid. The CIA projected its own paranoia and obsessions onto LSD and mistook those attributes as if they were inherent properties of the drug itself. Thats an example of what British philosopher Alfred North Whitehead referred to as the fallacy of misplaced concreteness. Many LSD enthusiasts succumbed to this fallacy when they assumed that the same beatific vision would be shared by all if everyone took the sacrament (dose the president and the war will end!). For those with messianic dreams, LSD was tantamount to the Second Coming, a pill with world-changing implications.

But taking LSD does not guarantee that a persons consciousness will automatically be expanded or that one will necessarily have a religious epiphany or live a spiritual life thereafter. Under the right circumstances, however, the astonishing immediacy and experiential density of LSD can be conducive to deep insight and healing. Albert Hofmann, the Swiss chemist who discovered LSD, described it as medicine for the soul.

Today we are in the midst of a psychedelic revival. Psilocybin, the magic mushroom extract, has supplanted LSD as the go-to psychedelic among researchers. Fast-tracked by health authorities as a cure for treatment-resistant depression, psilocybin is not burdened by associations with sixties excess and social strife, which continue to stigmatize LSD. Hopefully, as efforts to decriminalize psychedelics gain momentum, we can move forward unencumbered by the misplaced fallacies of the past.