Hicks - The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution

Here you can read online Hicks - The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Pluto Press, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution

Dan Hicks

First published 2020 by Pluto Press

345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA

www.plutobooks.com

Copyright Dan Hicks 2020

The text of The Brutish Museums is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0).

The right of Dan Hicks to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 0 7453 4176 7 Hardback

ISBN 978 1 7868 0683 3 PDF eBook

ISBN 978 1 7868 0685 7 Kindle eBook

ISBN 978 1 7868 0684 0 EPUB eBook

This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin.

Typeset by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England

Simultaneously printed in the United Kingdom and United States of America

For Judy and Jack

The methods by which this Continent has been stolen have been contemptible and dishonest beyond expression. Lying treaties, rivers of rum, murder, assassination, mutilation, rape, and torture have marked the progress of Englishman, German, Frenchman, and Belgian on the dark continent. The only way in which the world has been able to endure the horrible tale is by deliberately stopping its ears and changing the subject of conversation while the deviltry went on.

W.E.B. Du Bois, The African Roots of War, 1915

And what of the museums, of which Europe is so proud? It would have been better, all things considered, if it had never been necessary to open them. Better if the Europeans had allowed the civilisations beyond the Continent of Europe to live alongside them, dynamic and prosperous, whole and unmutilated. Better if they had let those civilisations develop and flourish rather than offering up scattered limbs, these dead limbs, duly labelled, for us to admire. After all, by itself the museum is nothing. It means nothing. It can say nothing. Here in the museum, the rapture of self-gratification rots our eyes. Here, a secret contempt of others dries up our hearts. Here racism, no matter if it is declared or undeclared, drains all empathy away. No, in the scales of knowledge the mass of all the museums in the world could never outweigh a lone spark of human empathy.

Aim Csaire, Discours sur le colonialisme , 1955 (my translation)

In his manifesto for the Dig Where You Stand movement, Sven Lindqvist wrote, typed out in all-caps:

FACTORY HISTORY COULD AND SHOULD BE WRITTEN FROM A FRESH POINT OF VIEW.

BY WORKERS INVESTIGATING THEIR OWN WORKPLACES.

In their workplaces, Lindqvist explained, people have competence and know their jobs; their working experience is a platform from which they can see what is being done, and what is not being done. The example that Lindqvist gave was the Swedish concrete industry, and this book too is about the building and anchoring of foundations, about composite and liquid forms, and about how such forms are reinforced and harden over time but also about the degradation and fatigue of institutional constructions, their structural weaknesses and collapse, the dismantling and demolition of brutal faades and how among the rubble a prone edifice might be repurposed as some kind of bridge.

My own workplace, which is the subject of this book, is the University of Oxfords Museum of Anthropology and World Archaeology, where I am curator of world archaeology. In what follows, I have sought to follow Lindqvists invocations: to do research on the job, to dig into what we know, to use our specialist and sometimes esoteric technical knowledge to excavate new pasts and presents, perhaps even to seek to carve out better futures too. In the case of the Pitt Rivers Museum, this knowledge begins with what might be reasonably called a form of Euro-pessimism, by which I mean that the knowledge that Europeans can make with African objects in the anthropology museum will be coterminous with knowledge of European colonialism, wholly dependent upon anti-black violence and dispossession, until such a time as these enduring processes are adequately revealed, studied, understood, and until the work of restitution by which I mean the physical dismantling of the white infrastructure of every anthropology and world culture museum is begun.

It is thus a book written from Oxford, a self-consciously anglocentric account, with the conviction that European voices have a service to fulfil in the process of restitution: one of sharing knowledge of the process of cultural dispossession, and of facing up to the colonial ultraviolence, democide, and cultural destructions that characterised the British Empire in Africa during the three decades between the Berlin Conference of 1884 and the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, an episode that I reframe here as World War Zero. One of my main aims in addressing this past is to help to catalyse a new acknowledgement of the scale and horror of British corporate-militarist colonialism, as has begun to happen in the sense of the colonial past in some other European nations, including Germany and Belgium. Anthropology museums represent crucial public spaces in which to undertake this social and political process, which is a necessary first step towards any prospect of the decolonisation of knowledge in these collections. But this cannot be short-circuited by the mere re-writing of labels or shuffling around of stolen objects in new displays that re-tell the history of empire, no matter how critically or self-consciously.

In light of the sheer brutishness of their continued displays of violently-taken loot, British museums need urgently to move beyond the dominant mode of reflexivity and self-awareness in museum thinking, which often amounts to little more than a kind of self-regard, turning the focus back upon the anthropologist, curator, or museum as both object and subject of enquiry, performing dialogue with certain source communities. We need to open up and excavate our institutions, dig up our ongoing pasts, with all the archaeological tools that can be brought to hand, sometimes a teaspoon and tooth-brush, other times a pick-axe or a jack-hammer. Any museum object has a double historicity, of course its existence before and after the act of accession. But in the case of what loot became under the intellectual regime of race science in the late 19th century and early 20th century, in the museum, the second, most recent of these two layers is dominant. Far from any normal history of collecting or provenance, which could co-exist alongside studies of the lives of these objects before that act of taking, under the ultraviolent conditions of military looting through the sheer intensity of the violence witnessed under corporate colonialism, which took the form of an incendiary shattering of the bombs scattering loot from the event of 18 February 1897 to hundreds of museums across the western world the damage is renewed every day that the museum doors are unlocked and these trophies are displayed to the public. The ongoing British/brutish histories of acquisition must be reconciled before African pasts, presents and futures can be meaningfully understood from the standpoint of any Euro-American museum collection. The primary task for anthropology museums must therefore be, I suggest here, to invert the familiar model of the life-history of an object as it moves between social contexts, new layers of meaning and significance added with each new phase of its biography, sovereignty, of the attempted destruction of cultural significance, to write action-oriented necrographies death-histories, histories of loss of the primitive accumulation of museums, in order to inform the ongoing, urgent task of African cultural restitution, intervening through new kinds of co-operation and partnership between Europe and Africa, in which the museum will variously dismantle, repurpose, disperse, return, re-imagine, and rebuild itself. Excavating the knowledge of where Benin loot is located today, and urging each of the hundreds of institutions, individuals, and families that hold it today universities, museums, charitable trusts, local government, nation states, descendants of the soldiers who did the looting, private collectors to take meaningful action towards cultural restitution, informed by the understanding that the violence is not some past act, to be judged by the supposed standards of the past, but an ongoing event, is a big task. At the end of this book is a first provisional attempt to list where the Benin loot taken in 1897 is today please help to correct and expand this knowledge, so that in a revised edition of this book we can update the list, and can start to count up the returns.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

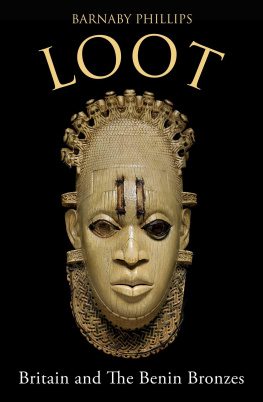

Similar books «The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution»

Look at similar books to The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.