SIMPSON

IMPRINT IN HUMANITIES

The humanities endowment

by Sharon Hanley Simpson and

Barclay Simpson honors

MURIEL CARTER HANLEY

whose intellect and sensitivity

have enriched the many lives

that she has touched.

The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous support of

the Simpson Humanities Endowment Fund of the University of

California Press Foundation, which was established by a major

gift from Barclay and Sharon Simpson.

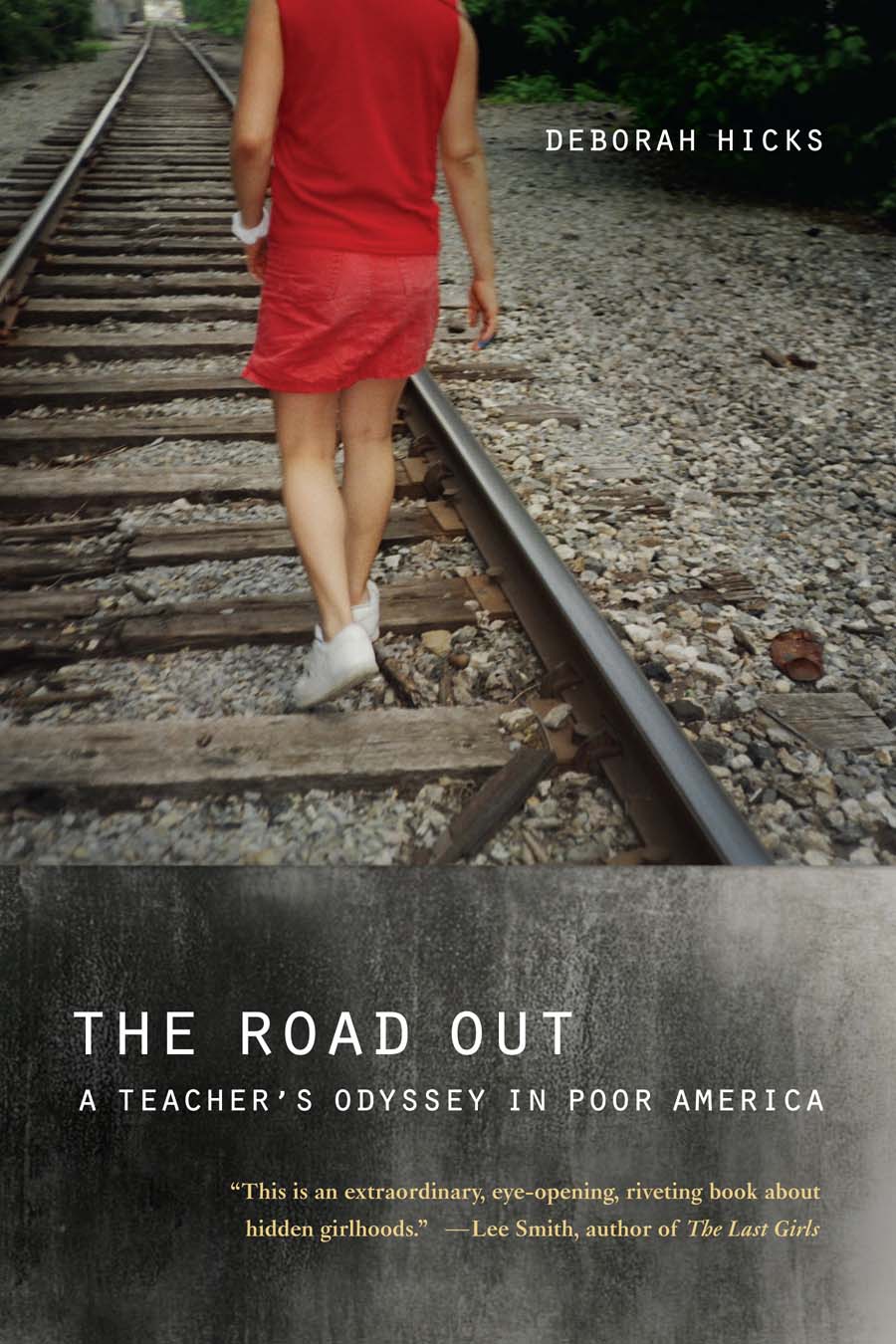

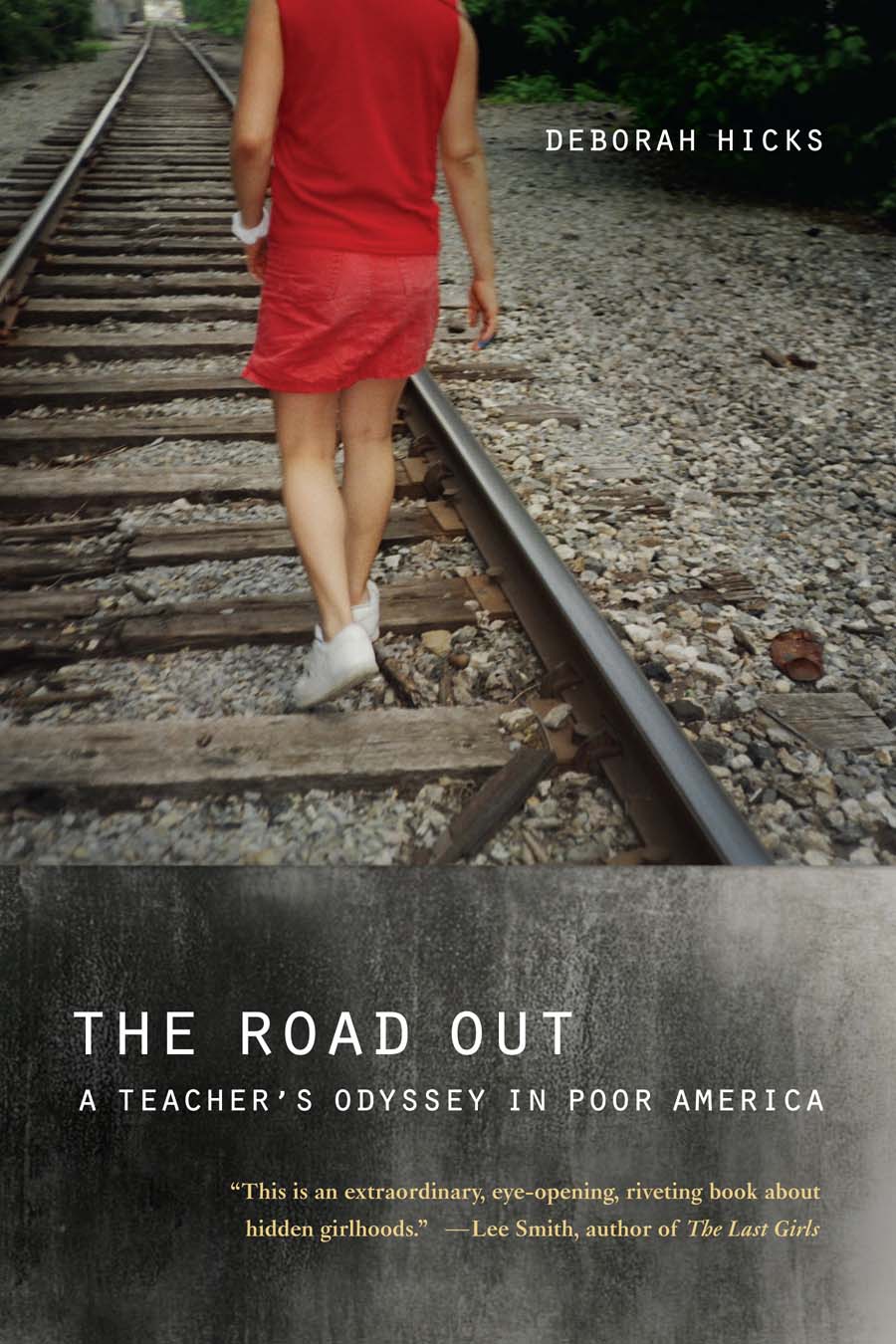

The Road Out

The Road Out

A Teachers Odyssey in

Poor America

Deborah Hicks

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS

BerkeleyLos AngelesLondon

University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu.

University of California Press

Berkeley and Los Angeles, California

University of California Press, Ltd.

London, England

2013 by Deborah Hicks

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hicks, Deborah.

The road out : a teachers odyssey in poor America / Deborah Hicks.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-520-26649-0 (cloth : alk. paper)

eISBN 978-0-520-95371-0

1. Poor [low income?] girlsEducationOhioCincinnati. 2. Poor whitesEducationOhioCincinnati. 3. Poor girlsBooks and readingOhioCincinnati. 4. Poor girlsOhioCincinnatiAnecdotes. Hicks, DeborahAnecdotes. I. Title.

LC4093.C56H532013

Manufactured in the United States of America

21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

In keeping with a commitment to support environmentally responsible and sustainable printing practices, UC Press has printed this book on Natures Book, a fiber that contains 30% postconsumer waste and meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z 39.481992 ( R 1997) (Permanence of Paper).

I want to be lifted up

By some great white bird unknown to the police,

And soar for a thousand miles and be carefully hidden

Modest and golden as one last corn grain,

Stored with the secrets of the wheat and the mysterious lives

Of the unnamed poor.

James Wright, The Minneapolis Poem,

Shall We Gather at the River

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

AUTHORS NOTE

The stories recounted in this memoir are drawn from my work as a teacher between 2001 and 2004, and my subsequent visits and interviews with my former students between 2005 and 2008. Scenes from my childhood in a small mountain town fill in the layers of a narrative that begins with my experiences as a working-class girl and follows my journey as a teacher for other girls who lacked opportunity or access. Though I grew up in small-town Appalachia and my students were coming of age in an urban ghetto, we were connected through a twist of history. Their elders were largely migrants from Appalachia who, in the postwar decades, had left family farms and coal mines in eastern Kentucky and West Virginia to seek a better future for their children in the city.

The basic facts of this chronicle are this: I grew up in Appalachian North Carolina, the daughter of working-class parents. My childhood was tainted not just by economic distress but by the things that often go with such distress. My parents could never escape the traumas of their dirt-poor childhoods, and I left through the only escape hatch available to a working-class girl: education. Later in life, I found myself in Cincinnati for a university job and decided to teach part time in an elementary school in one of the poorest neighborhoods in the city. I first worked as a volunteer in a second- and then third-grade classroom, teaching reading and writing. It was in these classrooms that I met the girls who would later become my students. I decided to form a unique class, just for girls, and we met each week during the school year and daily over the summer. Our curriculum was simple: literature and story, including these young girls own life stories.

I have chosen to recount my journey in a way that portrays my students and my teaching work from the inside. In so doing, I have adapted the tools of a novelist to the task of reporting on my experiences as an educator. Readers are drawn into the inner worlds of my students, not only in my classes, but also in their homes and on the streets. Discerning readers might wonder how I could garner such intimate material, how I could know what a girl might be thinking or feeling at a given moment. The length of time I taught the same girls in our small class, four years, was one resource that allowed me to go deep, and most importantly, to garner the trust that allowed these girls to reveal their inner thoughts, feelings, dreams, and anxieties. Coupled with time were other tools. I pored over thousands of pages of detailed written notes, transcriptions from recordings of all our classes, and interview materials in order to recreate the scenes depicted in this memoir. Each moment of this narrative in which a reader is able to peer into the inward thoughts of my students is tied to an outward exchange during our classes, to my interviews, or to a girls written journal.

This does not of course mean that the experiences recounted are without the overlay of my own way of seeing and understanding things. Though this book portrays eight lives, including my own, there is just one narrator. I hope that one day the girls portrayed in this book will write their own memoirs, and in so doing fill in the spaces where I could not see or hear with enough clarity to tell the complete story of anothers life. And yet, I have not pulled back from the challenge of recounting my students inner childhood worlds. I have portrayed their worlds more seamlessly than a purely sociological study would, with the intent of helping to bring readers inside the hidden lives of poor whites. This is not done merely for literary effect. I believe that more just actions and social policies, including our response to the crisis of education for the poor, can only come from deeper understandings of these still mysterious lives. It is my dream that readers of this chronicle will be moved to a different kind of thought and action, not by means of a new assortment of facts and statistics but through the intimacy of a story.

Chapel Hill, North Carolina

February 2012

INTRODUCTION

A Teacher on a Mission

When I was a young girl growing up in a sleepy Appalachian paper mill town, I had a lot of dreams for a girl with limited opportunity. Probably the biggest of all my dreams was just to get away from where I was. I spent most of my girlhood in a perpetual state of roaming. The road in front of the wood-frame house we rented in my early years was paved but it soon turned to dirt, as it wound out of town and toward the hills and hollers nearby. At home were my parents and one brother, only ten years old but already trouble. He was a gangly, miserable kid who was as disturbed as he was smart; possibly he suffered some neurological damage from his difficult entry into the world, a city doctor would later surmise. My father donned his workmans clothes and packed his lunch pail, happy to get out of the house. My mother took Valium and Darvon and slept off her anxiety and depression. Off I would go, a plucky five-year-old in search of a little girls dreams in the unlikely landscape of working-class Appalachia.

Next page