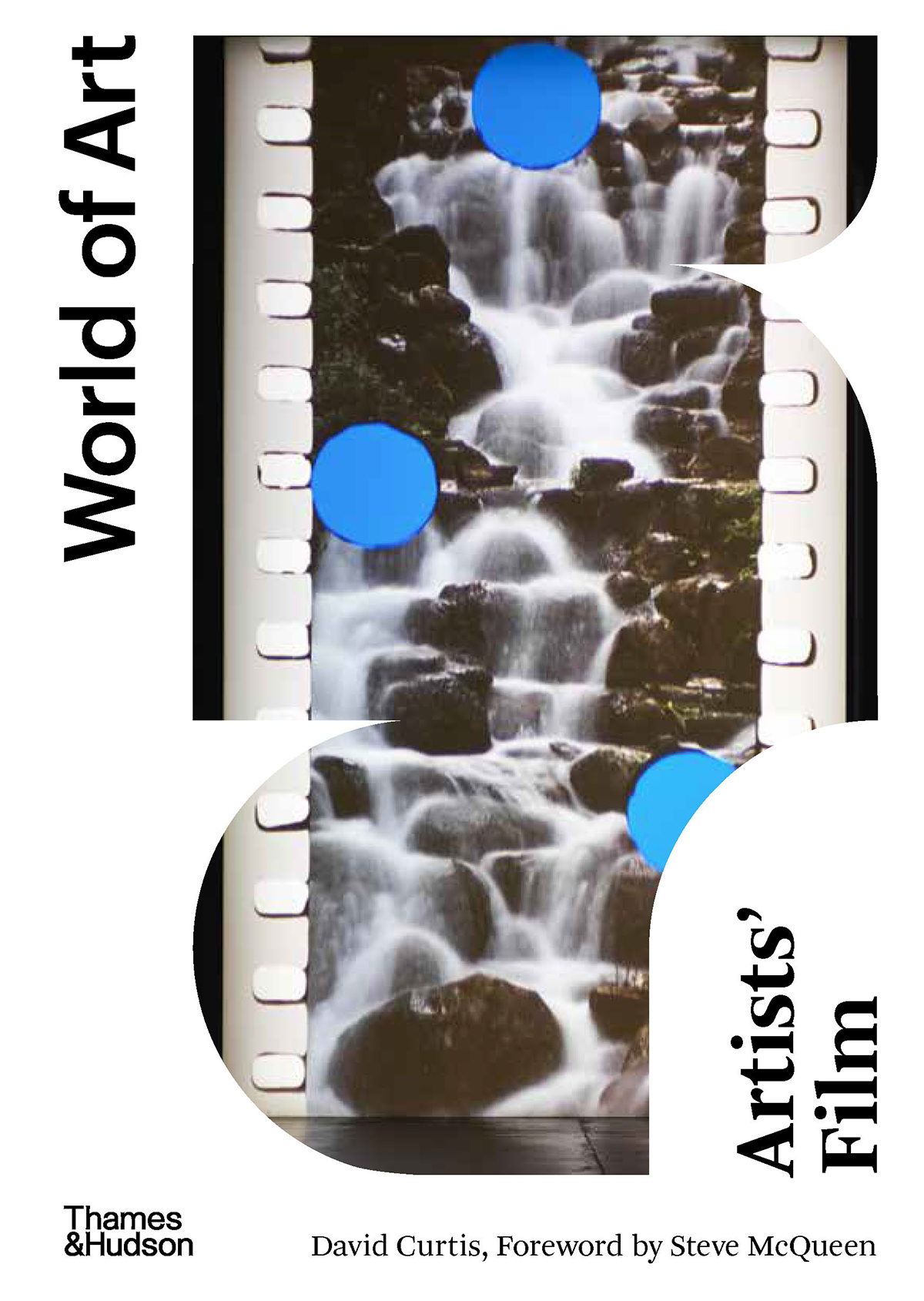

Dziga Vertov, Tchelovek s kinoapparatom (Man with a Movie Camera), 1929 (detail)

About the Author

David Curtis is a leading authority on artists films. His books include Londons Arts Labs and the 60s Avant-Garde (2020) and A History of Artists Film and Video in Britain (2006). He was responsible for artists films at the Arts Council of Great Britain from 1977 to 2000, and curated A Century of Artists Film in Britain at Tate Britain, London, in 20034.

Contents

Acknowledgments

Many hands have helped give shape to this text. Ryszard Kluszczynski gave early encouragement; Tim Cawkwell, Phillip Drummond and my partner Biddy Peppin all contributed thoughtful editing at early stages; Heather Stewart, William Fowler and Camilla Erskine at the British Film Institute usefully commented on the text while it was still homeless; Roger Thorp at Thames & Hudson saw the books potential and boldly commissioned it; Nicky Hamlyn and Roselee Goldberg offered invaluable, detailed suggestions at a vital late stage. At Thames & Hudson, Kate Edwards, Mohara Gill, Jo Walton, Adam Hay and Celia Falconer have steered the book towards the printers with quiet professionalism. Many artist friends have shared ideas with me over the years, so helping to deepen and expand my understanding of this medium; indeed, enjoying and often being challenged by their work is what sustains me. Not least among these artists is Steve McQueen, who has generously contributed a foreword to this book.

Foreword

Steve McQueen

In the summer of 1993, David Curtis came to Goldsmiths College to assess the final year Fine Arts undergraduate students, of which I was one. At that time I had been accepted as a graduate of film at NYU and my mind was elsewhere.

My first encounter with David was in a dark room with a rattling 16mm projector cutting light through the dark, illuminating my own and anothers naked bodies. The film was called Bear (1993). David stayed for two viewings of this ten-minute, silent black-and-white film, then left, saying nothing. Shortly after I bumped into him in the corridor, where he spoke with a soft voice barely audibly and asked questions about my film. I got the impression he was enthusiastic, but I wasnt sure if he liked it. He gave me a card and invited me to his office at the Arts Council, where he worked.

I arrived one typically overcast London day and was shown in by his trusted deputy Gary Thomas. David began to say how much he admired Bear and asked what I was doing next. I told him I was off to New York and wanted to focus on feature films. He looked surprised, but said if I ever returned I should contact him if I needed assistance in making another project. I smiled and said thank you. A year later, with my tail between my legs, I sheepishly got in contact with David asking for assistance to make a new project. He (or his committee) kindly gave me 5,000 and I took it to make my second artwork, 5 Easy Pieces, which I showed at the ICA in 1995 in the exhibition Mirage. From that day I never looked back.

David is the only person I know who has an encyclopaedic knowledge of and a passion for film in all its possibilities. Long before it became popular in the 1990s to work in film or video, David was committed to the medium; I had no idea that someone like him existed in the UK until I met him. His dedication to and knowledge of film and video is incomparable.

This book is an important document that describes the development of artists film in all its forms, and should be treasured. Thankfully it will enable Davids vast experience and knowledge to reach future generations of artists, filmmakers, researchers and academics, whose lives may be changed by it as mine was.

Artist: person who practises or is skilled in an art, now esp. a fine art; a person who has the qualities of imagination and taste required in art; a painter or draughtsman; a performer esp. in music; a person good at, or given to, a particular activitya learned mansomeone who professes magic, astrology, alchemy etc.

The Chambers Dictionary

This dictionary definition from the 1990s, still gender-biased, struggles as we all do to concisely define the role of the artist in society. In this book, artist is employed as it is most commonly understood: to describe individuals who practise and are skilled at a particular activity, in this case, working with the moving image.

It should hardly need stating that the giants of mainstream cinemas past Renoir, Antonioni, Varda, Ray, Tarkovsky et al. have as much right to be called an artist as any of the around 400 moving-image makers included in these chapters. They too managed to establish a distinctive vision, despite working in the context of an often hostile entertainment industry. But their work is of a different scale and intention to that described here, contributing instead to a long-established history of the narrative arts the novel, the play or the history painting. The relationship of cinema director to film-making artist has been compared by some to that of prose writer to poet. The artists described here tend to work alone (as do painters and poets), often wholly outside or at best on the fringes of mainstream cinema and the commercial art market. And many, at least early in their careers, exhibit a willingness to shock to rock the boat. Often, they have struggled to make their voices heard, yet they have still had an impact on the evolution of the art form. This book is dedicated to these individuals (moving image alchemists, in the eyes of some).

When describing this field, historians have sometimes focused on the lineage of one particular branch of moving-image art for example, the experimental film, video art, expanded cinema or multimedia art. These medium-specific histories are important, but taken alone they can obscure the bigger picture of the artists contribution to film over the last 100 years. This introductory book brings these histories back together, discussing works thematically, whether film, video or installation, while respecting chronology and acknowledging an artists particular engagement with a chosen technology where important. The primary purpose here is to give a sense of the richness and diversity of this field, and the pleasures to be discovered within. These thematic groupings allow connections to be made across decades, continents and media. The social and political environments in which these artists worked is also outlined here, albeit sometimes briefly. Artists may work in isolation from their times or revisit ideas first explored decades earlier; what they bring new to their work is what matters.

This, then, is a single history: the story of creative individuals scattered across the world who have been attracted by the flickering screen and felt compelled to contribute their own images to it, film their shared language. This inclusive approach also recognizes that today, in the age of digital distribution, there are multiple ways in which artists films will be encountered in cinemas, on gallery walls and, probably most frequently, on the internet. Many of these forms are now far removed from the artists original expectations, a phenomenon discussed in . Hopefully this book will encourage readers to seek out and enjoy these encounters.

Next page