Contents

Guide

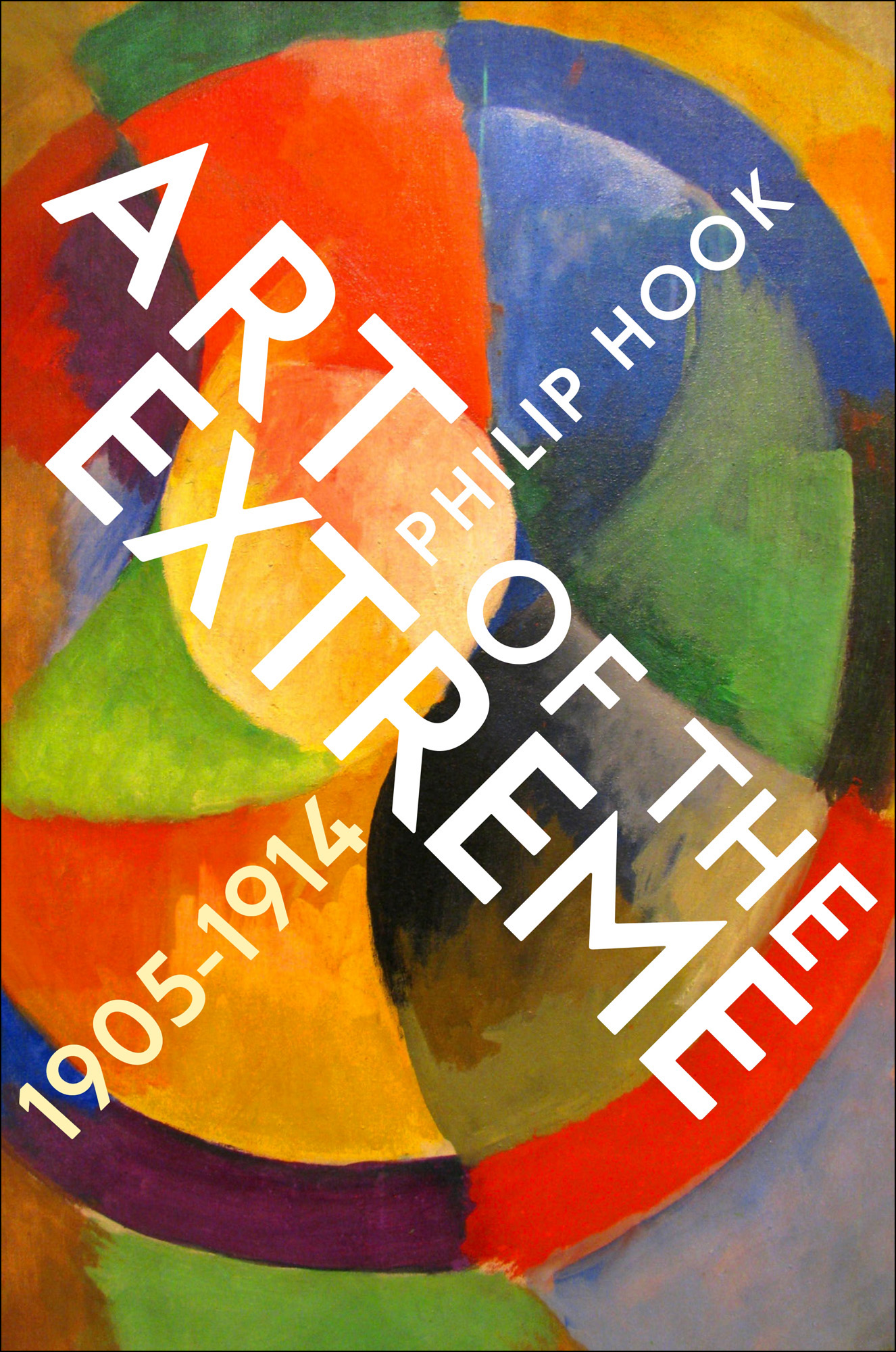

ART OF THE EXTREME

ALSO BY PHILIP HOOK

NON FICTION

Rogues Gallery

Breakfast at Sothebys

The Ultimate Trophy

Popular Nineteenth Century Painting

FICTION

An Innocent Eye

The Soldier In the Wheatfield

The Island of the Dead

The Stonebreakers

Optical Illusions

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by

Profile Books Ltd

29 Cloth Fair

London

EC1A 7JQ

www.profilebooks.com

Copyright Philip Hook, 2021

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78816 185 5

eISBN 978 1 78283 515 8

Introduction: A Tumultuous Decade

On 22 March 1905 Paula Modersohn-Becker, a twenty-nine-year-old German artist on her second trip to Paris, visited the exhibition of the famously radical Salon des Indpendants. The walls are covered in burlap and there the pictures hang, with no jury in sight, alphabetically arranged in colourful confusion, she reported. Nobody can quite put a finger on exactly where the screw is loose, but one has a strange feeling that something is wrong somewhere. To the young German imagination, torn between innate orderliness and a guilty urge to experiment, the loosening screw is both an ominous and an exciting metaphor. Modersohn-Beckers artistic antennae have picked up a warning that a defence is about to give way. What would be unleashed? No one was quite prepared for the deluge that broke over the European art world through the next ten years, a deluge of modernist invention that would shake traditionalist convention to its foundations.

The year 1905 marks the beginning of a decade widely regarded as the most momentous in the history of modern art, quite possibly the most important in post-Renaissance art history. In quick succession, works of art were created that defined the direction of modernism. New movements poured out after each other with a chaotic volatility, like water gurgling in a bottleneck: Fauvism, Expressionism, Cubism, Futurism, Orphism, Rayonism, Vorticism, plus the breaching of the final frontier of Abstraction in 1913. But only in retrospect does their significance become clear. And it is easy to forget that these avant-garde movements, central to all the art history of the period written later, occupied only a small minority of painters operating at the time. There was a conventional majority, oblivious to modernism, who continued to paint pictures in the traditional manner to please rather than challenge the public.

The pace of life was perceived to have quickened in the new century. Trains, automobiles, telephones and the cinema all contributed to that acceleration. Advanced artists were responding to it, not least in the tempestuous way that they were applying paint to canvas. But there was an intensification of activity in other parts of the art world too. The ten years leading up to the First World War saw a huge boom in the market for old master pictures, as American moguls became rich to an unprecedented degree and found that what they wanted more than anything else was to surround themselves with trophies of the great European art of the past. This early form of money laundering, putting your new wealth into old art and thereby transforming it into old money, was a seductive and inflationary process. The highest price ever paid for an old master stood at 100,000 in 1905. In 1914 the world record had risen to 310,000. [Approximate Exchange Rates 190514: 1 = 5 US Dollars = 25 French Francs = 20 German Marks = 10.5 Austrian Crowns = 9 Russian Roubles] But as more and more impoverished European aristocrats waved goodbye to their treasures in exchange for comforting quantities of dollars, a threat was perceived to the cultural heritage of Europe. Pertinent new questions began to be asked about the role of museums and the importance of national collections.

What was the artistic temperature across Europe in the first days of 1905? At the latter end of the nineteenth century, there had been widespread reaction against the entrenched conservativism of the official academies and the traditional art that they encouraged. In France, Belgium, Germany, Austria and Scandinavia artists had set up their own breakaway organisations in order to provide outlets for exhibiting to the public (and selling) the more advanced art that they were producing. In the German-speaking world, these were known as Secessions. In France the Salon des Indpendants, in opposition to the official Salon, had been established by the artists Georges Seurat and Odilon Redon in 1884. Membership was open to all, and a degree of anarchy prevailed. Funds were mercilessly raided by members wanting fishing rods for use on the nearby Seine. At one point the cashier had to defend himself with a revolver. More recently, in 1903, the radical Salon dAutomne had also come into existence as an alternative to the alternative. There was a selection jury, but that jury comprised artists of strong modernist persuasion. Thus at the Salon dAutomne there was a sharper and more intelligible focus on modernism.

Indeed one of the features of the new century in Europe was the increasing frequency and reach of art exhibitions. In the mid nineteenth century the only shows of contemporary art that people took seriously were the official ones, such as the Salon des Beaux Arts in Paris, the Royal Academy in London and the Academy in Berlin. The emergence of the alternative Paris salons and the German Secessions at the turn of the century was followed by a proliferation of exhibitions of modern art. They were facilitated by the increasing efficiency of communication and transportation, and they came thick and fast, large, small, conventional, subversive, international, progressive, held not just in museums and official institutions, but in dealers galleries and even in private houses. It should not be forgotten, however, that even in 1905 far more art lovers attended the official, conventional shows at the Salon and the Royal Academy than patronised the avant-garde. And of those who did venture, experimentally, into galleries showing advanced work, the reaction of the majority was still either derision or outrage.

So what, in 1905, did artists think a painting should be; what should it do? The majority, the traditionalists, still felt that its primary objective remained the creation of beauty, and that as far as possible it should tell an uplifting or at least amusing story. But the much smaller number of largely younger artists who comprised the European avant-garde were in rebellion against these ideas. They knew their priorities were different, that in the words of Kandinsky it couldnt go on like this. At the beginning of the year 1905, however, they were having difficulty in formulating a coherent definition of the purpose of painting. Recent ideas that had driven artistic experiment were running out of steam. The Impressionist credo that a painting should be a perfect replication of the optical impression made on the eye had been pushed as far as it could go. It was now entering its final cul-de-sac in the shape of neo-Impressionism, which imposed on the picture surface a quasi-scientific divisionism of dots or dashes of unmixed colour. Plenty of artists were asserting their modernity by painting in a pointillist style, in Paris and across Europe: from Prague to Brussels, from Munich to Milan. But for the innovators on the most cutting edge of experiment, the search for a new direction was on. The Secessions were looking a little tired. In June 1905, a Whistler retrospective opened in Paris. It was attacked by critics as old-fashioned: Maurice Denis declared, Impressionism is finished; one has even come to doubt that it ever existed. On his first visit to Paris that summer Paul Klee offered the following considered assessment of Renoir: Facile, he called him in his diary, so close to trash and yet so significant.