For Luis

Copyright

Copyright Anne Whitehead 2003, 2018

First published in 2003 by Profile Books

This edition published in 2021 by Ligature Pty Limited

34 Campbell St Balmain NSW 2041 Australia

e-book ISBN 978-1-922730-21-3

All rights reserved. Except as provided by fair dealing or any other exception to copyright, no part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher.

The moral rights of the author are asserted throughout the world without waiver.

CONTENTS

I.

II.

III.

IV.

V.

VI.

VII.

VIII.

IX.

X.

There is a curious Argentine film, Miss Mary, starring Julie Christie, about an upright English governess on an estancia or ranch on the pampas. She struggles with isolation, social dislocation, authoritarian employers and her own sexual frustration, against a background of war in Europe and impending dictatorship in Argentina. Directed and co-written by the late Maria Luisa Bemberg in 1986, the story is, I understand, fictional. Certainly it is not about my Miss Mary, whose actual experiences in South America included being a governess on an estancia. But as Andre Gide said: Fiction is history which might have taken place, and history fiction which has taken place.

I

WATERWAYS

Squealing cockatoos shredded pine cones above me, four people were practising tai chi, suspended in the graceful gestures of passing clouds, an elderly couple shared their sandwich with the pigeons, and sounds of young kids playing soccer came from the grassy field nearby. In the late afternoon I was sitting on a bench under century-old treesjacaranda, fig, camphor laurel and Norfolk pinein the grounds of Stanmore public school, unusually extensive for Sydneys inner west and now made available after hours as a common for residents of this newly gentrified area. Ahead of me was the handsome main school building of russet brick and sandstone, erected in 1883, boasting three sets of stone stairs to a colonnaded verandah. It is a monument to the New South Wales colonys pride in its programme of free, compulsory and secular education, which in the 1880s had rapidly expanded literacy among the working class.

Mary Jean Cameron, an inspirational young teacher posted to the school in May 1891, welcomed her appointment there. But because of events that had their origin in Queensland in the very month of her arrival, she stayed just four years before resigning, leaving her pupils in tears as she departed. One of them recalled that she said goodbye to us and went away to a distant land but she was the kind of personality whose memory never fades.

I had come to the school in September 2002, as a ritual starting point for my own expedition, trying to imagine it when Mary was there, when the great trees were mere seedlings, for I was about to set off for that distant land on Marys trail.

Some time before her departure, Mary had set down her dilemma in deceptively confident handwriting in her journal:

This day my feet are set on the junction of three paths. It is imperative that I should choose one (or that I should drift along one). I know that if I choose I shall very likely take the wrong one, that I shall be some distance on my way before I find that out and that it will be then impossible to return ...

It was 1895 when she embarked on her intrepid journey from Sydney to the heartland of South America to join an experimental socialist utopia in Paraguay.

After the armed suppression of a five months long strike of over 10,000 shearers in Queensland in 1891, hopes of a social revolution, a republic, or just a better way of life in Australia had faded for many bushworkers. Then they listened to William Lane, a British journalist whose vision owed more to mateship than to Marx, a fiery supporter of their cause during the strike, who in his editorials in the Queensland Worker proposed a better way of life.

He called on the disenchanted to uproot themselves and sail to a faraway place where they could build a secular heaven on earth: a communal society in the backwoods where all would be equal, regardless of class, education and gender. From there they could one day emerge, a disciplined army of thousands, to lead the workers of the world to socialism. This was not a wild dream, an impossible hope, he insisted, all it took was the daring to act on itsomewhere far from the contaminating influence of class. Somewhere in South America. They could be an inspiration for workers in all lands, for the industrial poor of England, France and Germany, even perhaps for the peasants of Russia. They could write the future history of humanity on the rocks of the Andes!

In 1893 over 500 Australians, mostly male bushworkers and trade unionists, followed Lane to Paraguay to found their New Australia. But, by the time of Marys passage two years later, the utopian dream had fragmented: it had become a nightmare of harsh words, occasional punch-ups, litigious threats and two implacably opposed rival colonies.

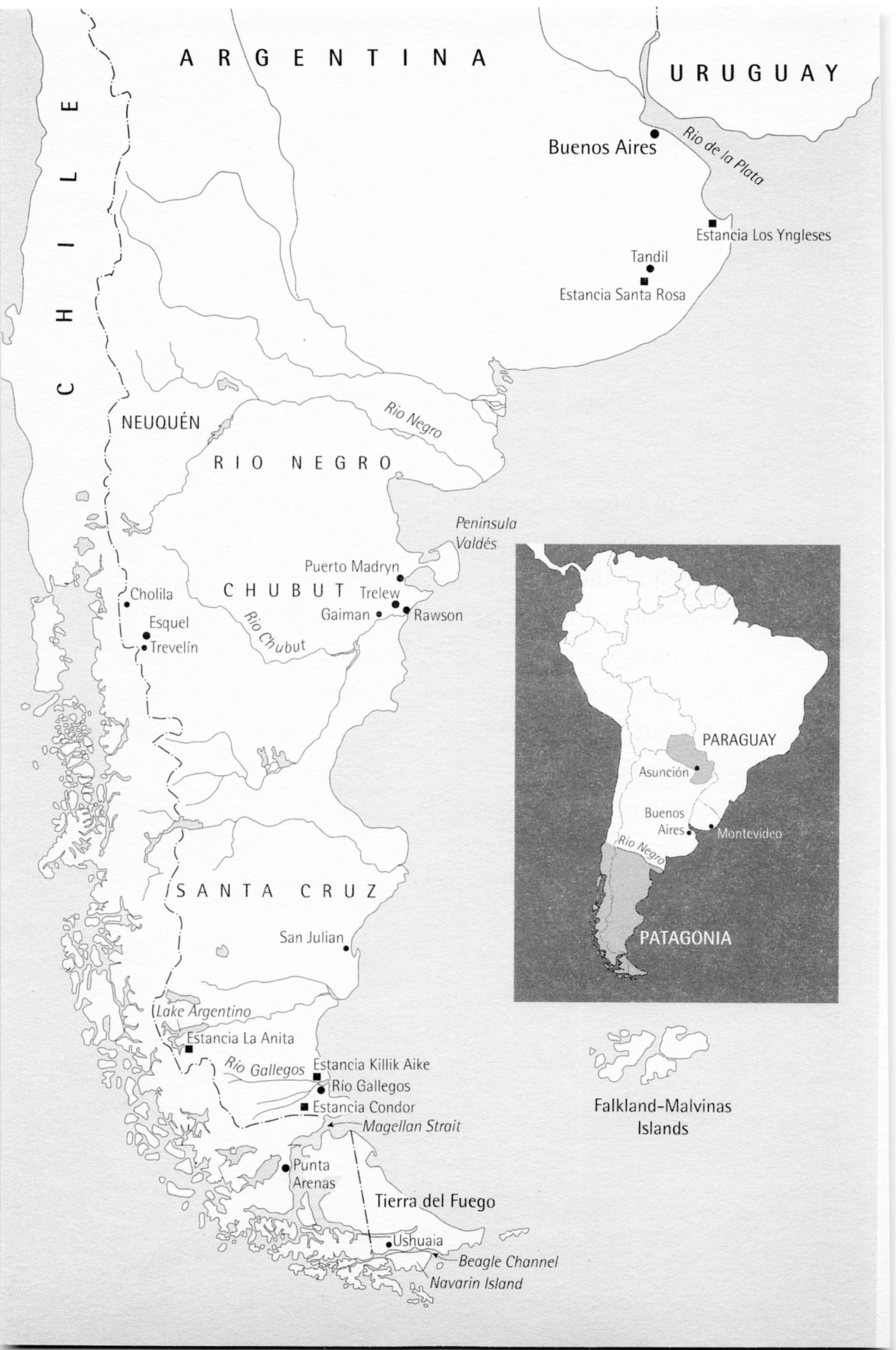

Despite this alarming development, Mary made her way to the breakaway settlement, Colonia Cosme, deep in the interior of Paraguayby mailboat to Montevideo, by paddlesteamer 1,600 kilometres up the great rivers, Ro de la Plata, Paran and Paraguay, then by steam train and at last by horseback, hearing the oranges go squish, squash under our horses feet, to reach a ragged collection of thatched huts in a jungle clearing. It was an extraordinary journey in the mid-1890s for a lone female with no language other than English, but Mary Cameron was an extraordinary young woman.

She was twenty-seven years old in 1892 when she met William Lanewho was to change the course of her lifeat one of the radical discussion evenings held above McNamaras bookshop in Sydney. She still had something of the country girl about hertall and lissom, with wide, brown eyes and auburn hair hacked unfashionably short by her own hand. One of her Stanmore pupils later recalled that Miss Camerons short crop of hair was a never-ending source of interest, and her jaunty appearance was accentuated by a sailor hat, a small hard straight-brimmed straw hat. Often too she wore a red sash at her waist, which she said was a declaration of her socialist beliefs.

Lane, the notorious newspaper editor, four years her senior, had been described by a cabinet minister as the most dangerous man in Australia, but he was physically unprepossessing. Prematurely balding, short-sighted behind gold-rimmed spectacles, he walked with a limp caused by a crippled left foot. But when he spoke he was compelling: he could focus on one person and inspire with his passion and sincerity or electrify hundreds with his eloquence.

Mary was ready to listen. Her very first teaching posting, in 1887, had been in Silverton, a silver-lead mining town near Broken Hill on the parched red plains of outback New South Wales. There her political beliefs had been shaped by observing the brutal working conditions of the miner fathers of her pupils, and the way concessions were only forced from the employer, the monolithic Broken Hill Proprietary Company, by the mens newly formed trade union. Her first political poem, Unrest, was published in July 1888 in the local newspaper, the

Next page