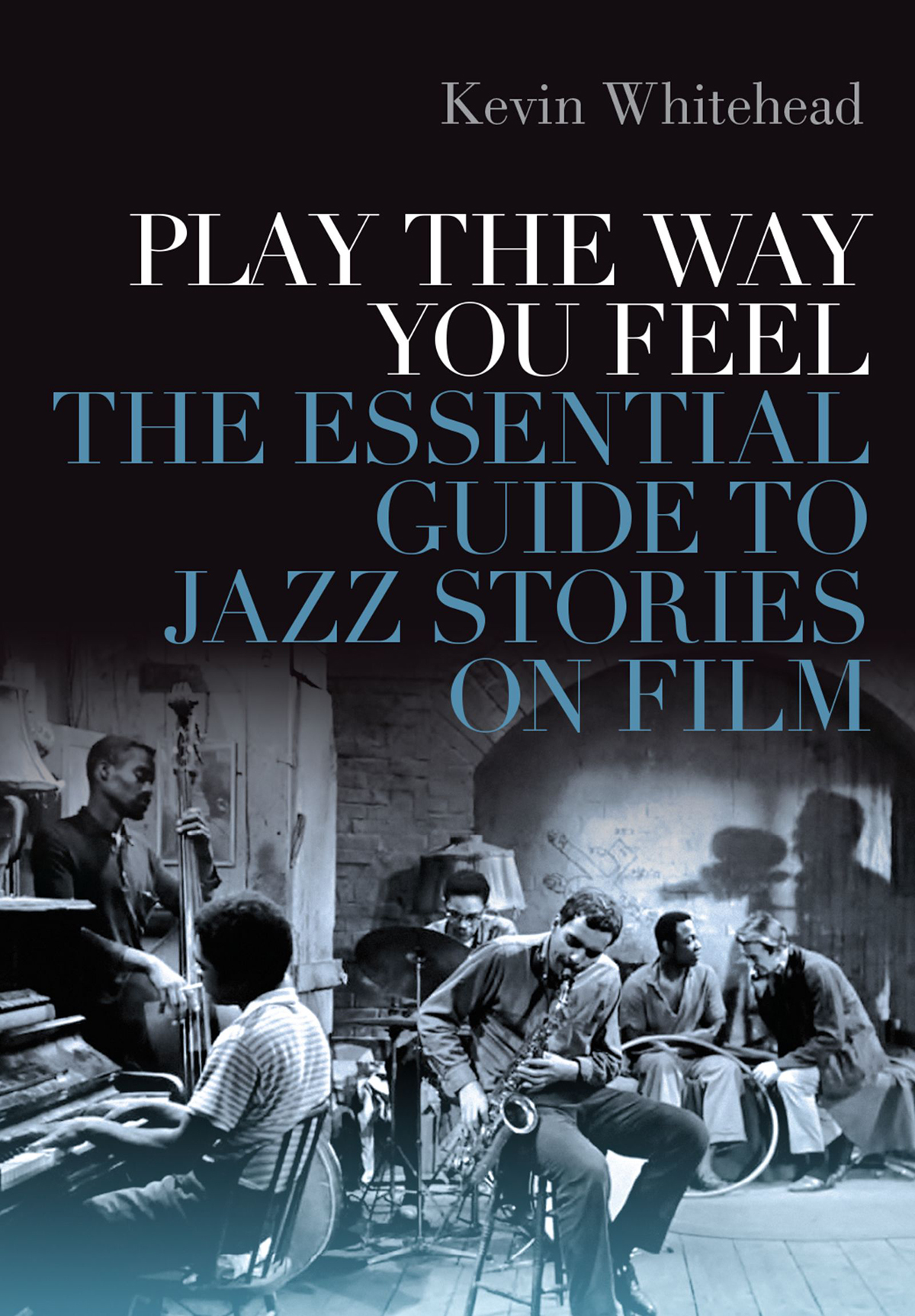

PLAY THE WAY YOU FEEL

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Whitehead, Kevin, author.

Title: Play the way you feel : the essential guide to jazz stories on film / Kevin Whitehead.

Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, [2020] |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019036474 (print) | LCCN 2019036475 (ebook) |

ISBN 9780190847579 (hardback) | ISBN 9780190847586 | ISBN 9780190847593 (epub) |

ISBN 9780190948306

Subjects: LCSH: Jazz filmsUnited StatesHistory and criticism. | Jazz musicians in motion pictures.

Classification: LCC PN1995.9.J37 W55 2020 (print) | LCC PN1995.9.J37 (ebook) | DDC 791.436dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019036474

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019036475

In memory of Sally Whitehead and Paul Wernsdorfer

and

for Lesley Ann

Id like to play like a bird fliesthis way and that, up and down, winging and swinging through the air. No controlwhistling, singing, shouting. Just music.

William Washington as Johnny Williams in Broken Strings

But this other music makes you feel like the circus is comin to town. Kinda turns you loose inside. You can stretch out and play what you feel.

Ronnie Cosby as young Jeff Lambert in Birth of the Blues

You just swing on out and play the way you feel like.

Kid Ory as himself in The Benny Goodman Story

I want to be in one of them bands where you could play free. What? Yall not even up on two feet yet!

Jaron Williams as Robert and Wendell Pierce as Antoine Batiste on Treme

Suppose it happens great one time and youd like it to happen exactly the same way, what do you do then?

Danny Kaye as Red Nichols in The Five Pennies

Contents

This book is an extended answer to a short question: How do movies tell stories about jazz and jazz musicians? Not just what they get right, or wrong, but how they tell it: jazzy, or not? And if so, how is that jazziness conveyed? Play the Way You Feel is partly about jazz movies as a narrative tradition with recurring plot points and story tropes, and we will trace their spread not just through the best-known films that deal with jazzthe likes of Young Man with a Horn, Lady Sings the Blues, or La La Landbut also overlooked and low-budget features and TV movies: any pertinent commercial release in English we could identify and view. There are also shorter discussions of some nonjazz features and a few television episodes that touch on the music, plus longer looks at jazz-related TV series Staccato and Treme.

Play the Way You Feel is also a practical guide: a music-loving movie-watchers companion and reference. Within the text, principal films discussed get a heading with pertinent credits; films dealt with more briefly are identified in boldface. They are discussed chronologically, with occasional swerves for the sake of thematic clarity (and indexed in the back).

Jazz and the movies make natural allies. These signature twentieth-century art forms grew up side by side, building on extant traditions. Jazz slowly coalesced out of blues, ragtime, field hollers, spirituals, and brass band music just after 1900, around the time the spectacle of moving pictures was evolving toward storytelling. Early synchronized sound films in the late 1920s were likewise amalgamated from creative borrowings: part staged theatrical, radio play, and variety show.

Sound recording was around before silent movies geared up, but jazz wasnt caught on record until around 1917. Movies with sound would break through a decade later, with 1927s The Jazz Singer, a film famously light on jazz content. And both jazz and the sound film evolved amazingly quicklythe former in the mid-1920s, once jazz recordings become common, no less than the talkies by the early 1930s.

Jazz and film are performance arts that unfold over time. Making that time fly is all about rhythm, and patterns of tension and release. Jazz musicians liken improvising a solo to telling a story (maybe inspired by the story the songs lyric tells). These arts may employ parallel syntax, ways to make that story ebb and flow.

Both devices helped foster greater expression and a star system. Armstrong became the most famous jazz musician everin no small part because he appeared in so many films.

Jazz musicians would seem ideal movie heroes: artists whose moment of creation is a public, audible spectacle. Improvising on a bandstand is kinetic, photogenic, and romantic. And for a while anyway, jazz represented a kind of artistic and cultural sophistication. Spotlighting extraordinary individuals, jazz movies occasionally ponder where musical talent comes from. We will meet all kinds in the stories that follow: child prodigies, naturals who pick up the music the first time they hear it, hard workers with a painstaking practice regimen, talented players diverted into soul-killing commercial work, even non-improvisers taught to fake it.

The interactions among jazz musicians, on or off stage, are complex and multifaceted; how do films attempt to portray that dynamic? Jazz champions improvisation, but the old studio system, with its massive support structure and complex production schedules, was inimical to improvisation as a concept (even as a few directors found ways to harness improvisational genius and energy). How does the tension between extemporizing loners and team players work itself out?

Such movies are a key point of intersection between jazz and more broadly popular pop culture. And yet, generally speaking, these films get little respect. Cinephiles balk at the melodrama, recycled plots, and compromised roles for black actors, where they appear at all. Reputable film scholars may mangle plot details or confuse one film for another.

On the jazz side, their reputation is even worse. As a trumpeter friend put it, Why would I watch a movie about Miles Davis when I can watch the real Miles on film? Even meticulous biographers breeze past or ignore musicians screen appearances, and tartly dismiss biopics with their gross fabrications. Jazz folk rue the musical inaccuracies and absurdities, the poor miming of playing instruments, and more importantlyas well seehow the movies whitewash jazz history. In film after film, African Americans, who invented the music, get pushed to the margins when white characters dont nudge them off screen altogether.