Table of Contents

Guide

The Final Spectacle

ISBN 978-3-11-048668-1

eISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-049748-9

eISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-049509-6

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018956403

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie;

detailed bibliographic data are available on the internet at http://dnb.dnb.de.

2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Copyediting: Kristie Kachler

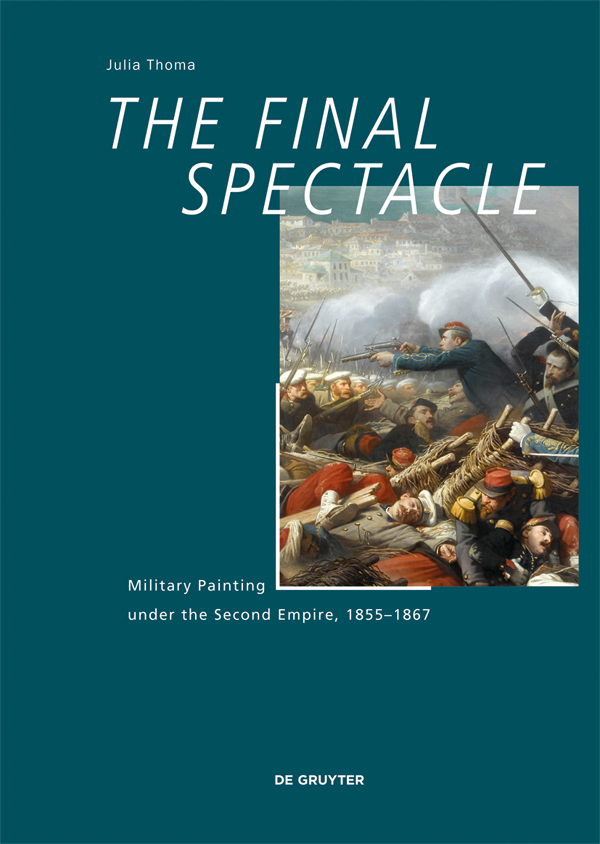

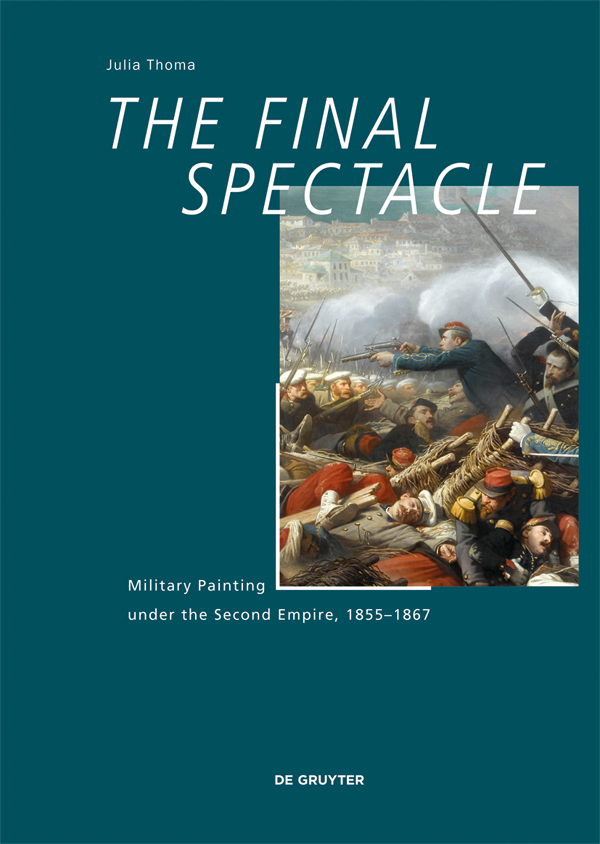

Cover illustration: Adolphe Yvon, La gorge de Malakoff (8 septembre 1855) (campagne de Crime),

1859, oil on canvas, 500 750 cm, Chteaux de Versailles et de Trianon, Versailles.

www.degruyter.com

Acknowledgements

The present book is a lightly revised version of my PhD dissertation, submitted at the Courtauld Institute of Art in 2013. Its title, Military Painting under the Second Empire , suggests the broad scope covered: the entire corpus of French military painting during the two decades of Napoleon IIIs martial regime. Given the breadth of the study as well as my attempt to bring together various discplines and methodologies to contextualise the importance of military paintings at this moment in history, publications touching on individual aspects of my study have naturally proliferated since early 2013, when my thesis was essentially completed. I have included the most relevant contributions in my bibliography and flagged them in the footnotes.

For their support in helping me to realise my dissertation and its publication, I would like to extend my gratitude to numerous institutions and individuals. John Houses consistent encouragement and enthusiasm for my research subject first led me to embark on this project. I am very grateful for having had the privilege to benefit from his vast knowledge and inspiring way of thinking about art history. I owe a special debt of thanks to Satish Padiyar for having taken over the supervision of my thesis in such a proactive and inspiring way. Working with him has been a real joy, and his generous guidance and commitment as well as incisive readings of drafts have truly enriched my work. I thank Melanie Vandenbrouck for having been my mentor and critic and for our discussions on Vernet. I also wish to thank Stephanie Buck for her support and for consistently challenging me. I benefitted enormously from the intellectual stimulation and critical feedback of other colleagues and friends, including Wolf Burchard, Mary Camp, Martina Caruso, Anna Fukuda, Ashley Robertson Givens, Harriet Griffith, Katie Hornstein, Nancy Ireson, Maud Jacquin, Alister Mill, Lois Oliver, Edward Payne, Virginia Rounding and Rachel Sloan. My thesis was financially supported by a Dr Martin Halusa Scholarship.

Outside the art history realm, a multitude of individuals have assisted with this project. I wish particularly to thank the historian Orlando Figes for engaging with my research about the Crimean War and for sharing his knowledge as I planned a travel route to the battlefields and memorials in the Crimea in 2012. General Sir Hugh Beachs expertise in military history often opened up new interpretations of the paintings treated.

In France, I would like to thank collectively the committed staff in museums, archives and libraries who have taken the time to respond to my questions, assist me in my hunt for reproductions of paintings that are rolled up or lost and granted me free image rights. I am especially indebted to Frdric Lacaille, curator for nineteenth-century paintings in Versailles, who continuously lent his insights to my research over the course of my thesis and beyond. I also owe much gratitude to Gilles Dupont, a specialist on Alexandre Protais, who shared his knowledge of the artists biography.

My thesis would not have been published without the feedback and inspiring viva discussion with my external examiners, Susan Siegfried and Tom Gretton. For realising the publication of my thesis at De Gruyter, my thanks go to Katja Richter, Anja Weisenseel and Kristie Kachler.

I owe a vast debt of gratitude to my family, who have been consistently encouraging and generously supportive. The thesis and its publication would not have been possible without the unconditional support and love from Konrad Thoma.

Abstract

Under the title The Final Spectacle: Military Painting under the Second Empire, 18551867, this book explores how newly invented formal strategies allowed the genre of military painting to remain the conduit of sociopolitical endeavours despite the evolving technologies of news coverage. Its reference point is the Universal Exhibition of 1855, where the critical reception of Horace Vernets (17891863) retrospective exhibition highlighted the political implications of his unprecedented artistic strategies for visualising war. The study traces Vernets artistic legacy and the influence of the newly emergent spectacle culture in the oeuvres of the next generation of artists among them Adolphe Yvon (18171893), Isidore Pils (18131875) and Alexandre Protais (18261890) , who were asked to commemorate the Second Empires military exploits on canvas.

The Crimean War (18531856) in particular gave rise to a new era in the genre of military painting when the arts administration asked eighteen artists to contribute forty-four paintings to a Salle de Crime in Versailles. Having to win over public opinion that was still fluctuating between resentment at the young Empires failure to keep its initial peace promises and acceptance of the semi-successful outcome of the war as having restored Frances glory, the paintings cover a range of genres and are eclectic in style, from confrontational pictorial rhetoric to landscape paintings of the wars terrain that distance the viewer from the military conflict. The room has not been given the scholarly attention that it deserves, considering that this major project formed an important part of Napoleon IIIs populist politics and was artistically innovative.

Moving on to the commemoration of the Italian Campaign (1859), examines public opinion to explain why the large propaganda piece La bataille de Solfrino (Salon of 1861) commissioned from Adolphe Yvon was a critical failure that heralded the decline of military painting as public spectacle.

The nationalist sympathy or produce a horrified recoil from the brutality of war the study spans a period that saw a diverse employment of artistic strategies in military painting conditioned by a changing political landscape, from the Universal Exposition of 1855 to the Universal Exposition of 1867.

Introduction

The Second Empire (18521870) was one of the most martial periods in the history of nineteenth-century France. This is reflected in the fact that military paintings received a new lease of life under the regime, becoming so central to it that contemporary art critics referred to them as peinture officielle . This was usually the first genre a visitor to the Salons of the Second Empire would have encountered, with large formats measuring up to six by nine metres dominating the central room. This visibility contributed to military paintings becoming the focus of the battlefield, as Thophile Gautier described the Salon in 1861, where enemy canvases competed ardently for victory in the middle of the tumult of criticism and praise.

*

During the Second Empire, when the works were still on public display at the Salons, most art critics discussed them in their Salon reviews, even if only to dismiss the genre in terms of taste or to set forth a political agenda. Discussions of the aesthetics of military paintings were inevitably politicised and used as a mode of either praising or criticising the regimes military policies.