DOSTOYEVSKY

EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVES

EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVES

A SERIES IN SOCIAL THOUGHT AND

CULTURAL CRITICISM

Lawrence D. Kritzman, Editor

European Perspectives presents outstanding books by leading European thinkers. With both classic and contemporary works, the series aims to shape the major intellectual controversies of our day and to facilitate the tasks of historical understanding.

For a complete list of books in the series, see page 77.

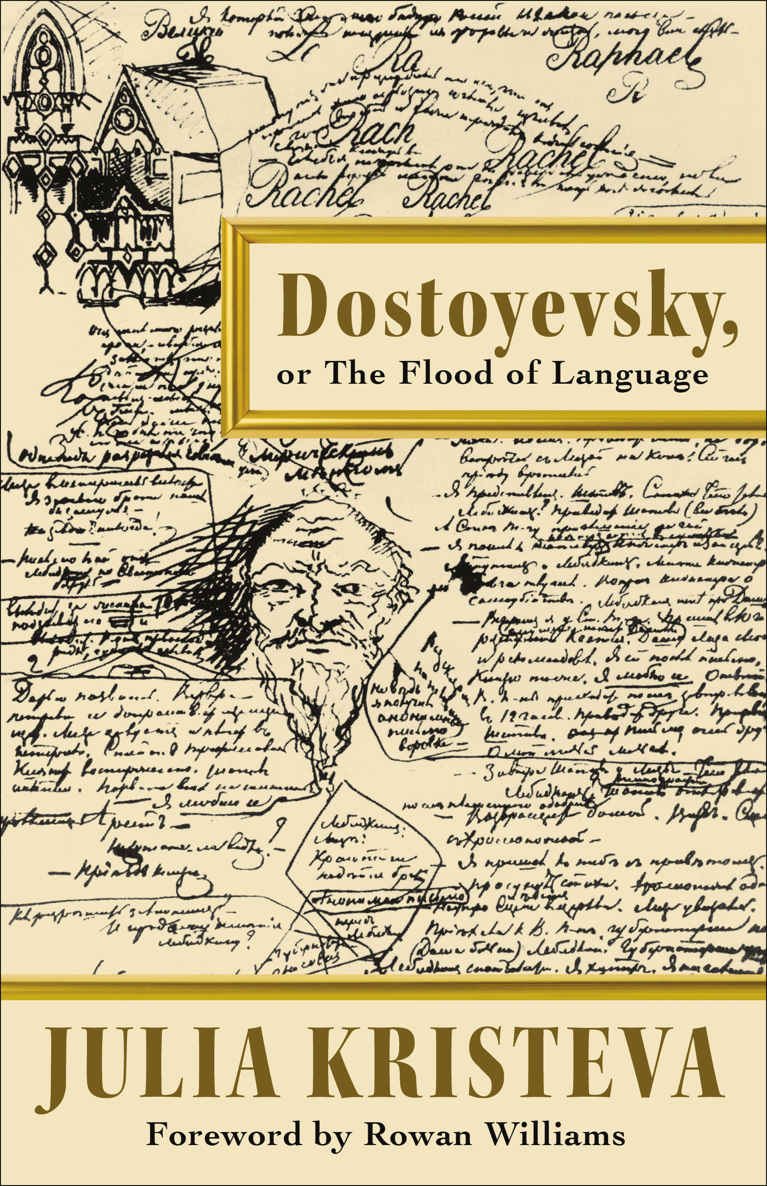

DOSTOYEVSKY,

OR THE FLOOD OF

LANGUAGE

JULIA KRISTEVA

TRANSLATED BY

JODY GLADDING

FOREWORD BY

ROWAN WILLIAMS

Columbia University Press New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup . columbia . edu

Originally published in French as Dostoievski, by Julia Kristeva,

Libella, Paris, 2020

Translation 2022 Columbia University Press All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Kristeva, Julia, 1941 author. | Gladding, Jody, 1955 translator.

Title: Dostoyevsky, or The flood of language / Julia Kristeva ; translated by Jody Gladding.

Other titles: Dostoievski. English | Dostoyevsky | European perspectives.

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, 2021. | Series: European perspectives | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021016634 (print) | LCCN 2021016635 (ebook) |

ISBN 9780231203326 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780231203333 (trade paperback) |

ISBN 9780231554985 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Dostoyevsky, Fyodor, 1821- 1881 Criticism and interpretation. | Dostoyevsky, Fyodor, 1821- 1881 Language. |

Russian literature 19th century History and criticism.

Classification: LCC PG3328.Z6 K776 2021 (print) | LCC PG3328.Z6 (ebook) |

DDC 891.73/3 dc23

LC record available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2021016634

LC ebook record available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2021016635

Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid- free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

Cover design: Julia Kushnirsky

Cover image: Manuscript page: Dostoyevsky, The Devils.

Gold frame: istockphoto.

CONTENTS

Kristevas Dostoyevsky: The Arrival of the Human vii Rowa n W illi a ms

Preface xxvii

Can You Like Dostoyevsky? 1

Crimes and Pardons 14

The God- Man, the Man- God 23

The Second Sex Outside of Sex 33

Children, Rapes, and Sensual Pleasures 44

Everything Is Permitted 52

Notes 67

Index 69

KRISTEVAS DOSTOYEVSKY:

THE ARRIVAL OF THE HUMAN

Rowan Williams

For the speaking subject, the parltre, that is a human being, nothing simply happens. However minimally, it is told, and so represented. For us, this is what happening means, and it is a seductive error to think of telling or representation as a kind of secondary refinement to some basic and unproblematic register-ing of stimuli. But the act of telling itself posits an area of obscurity, a hiatus between pure stimulus and its narration, in the sense that the act of telling opens up diverse possibilities, the unspoken potential for something to be said otherwise.

Division and duality are inscribed in speech: whenever something is said, we acknowledge its connection with what is said elsewhere and otherwise because if we didnt, what we said would not be communication at all.

So: we are touched; our material subsistence encounters the presence of what it is not. And to be a body in any intelligible sense to be something other than a bundle of organic stuff is to be animated into some pattern of coherent response to what it is not, to establish a continuity of reaction whose most complex expression is the speech we shape together as intelligent

viii Y Kristevas Dostoyevsk y bodies: the practice of activating and receiving material behaviors, especially but not exclusively noises, as signs, as invitations to examine and reexamine a what is not us that is more than an individual object of encounter, to map an environment. A crucial implication of this is that speech complicates and diverts desire or, to use the somewhat more technical term, it mediates desire. What we want is something we as speaking beings are bound to represent, and so our desire is inflected by the already represented desire of others and problematized by the obscurity identified in the act of representing, the awareness of the elsewhere and otherwise that representation entails. In this sense, representation accompanies the deferral of gratification; narrative puts off the moment of climax or fulfillment because that moment has to be an end to the joyous and alarming multiplic-ity of potential that language involves. All intelligent speech is to some degree an enactment of this foundational displacement; the sophistication of storytelling is a particularly focused and developed version of it. The narrator can be seen as someone familiarizing themselves with the void in language, digging for what lies within the dividedness at the heart, the ground zero or degree zero of thought, to borrow one of Kristevas summary phrases. The narratives that endure and impress themselves on widely diverse readers and hearers across time and space are those that allow us not exactly to inhabit this space, since it is not a place to live in, but to be constantly aware of its imminence. What Walter Davis calls the crypt of imagination, what Wilfred Bion calls the O in the psyche and the speaking subject, this is what a durable narrative needs to hold us to, offering the paradoxical gratification of deferral, the complex human delight of staying with the undetermined.

Julia Kristevas reading of Dostoyevsky is, in effect, a tour de force of linking this particular novelists practice with the

Rowan Williams Z i x

fundamentals of the psyche as a linguistic reality. It is a reading that pulls together the impact of the familiar Bakhtinian theme of Dostoyevskys polyphonic method, the centrality of dialogical exchange, and the less fully explored idea of the narrative writer as consciously holding themselves and the reader on the verge of the empty center of speech. They are in fact perspectives that belong together: if the essence of Bakhtinian dialogue is that everything and everyone is at the frontier of its opposite, this means that any determinate identity in the speech- world will be shaped by its refusal of what it is not; it is haunted by the unrealized potential of what has not been chosen and spoken. A dialogical and polyphonic form of telling

allows a to- and- fro between what is said and not- said, what is chosen and what is denied, by voicing different speakers. And Dostoyevsky is famously in love with creating pairings, twinnings between characters most dramatically perhaps with Myshkin/

Rogozhin and Nastasya/Aglaya in The Idiot and with the images of abusive and nurturing fatherhood in Fyodor and Zosima in Karamazov.

But there is a key distinction to be drawn between this dialogical embodiment of the diverse potentialities of language and the language that purports to come from the void itself

that is, from a place of pure arbitrariness and antidetermination.

This is the voice of the narrator in Notes from Underground, the naked statement of what lies in the clivage between voices: staying here or speaking from here is in fact ultimately to refuse language itself. The Underground Man cannot speak

Next page