Drawing Figures

A practical course for artists

Barrington Barber

Contents

Introduction

First Steps

Drawing the Whole Figure

Drawing Clothed Figures

Drawing from Life

Composition

Figures in Action

Figures in Detail

Styles of Figure Drawing

Step by Step to a Final Composition

Introduction

From the mid 1500s onwards, composition was considered to be the most prestigious area of art, which made it of primary interest to the greatest artists of the time. Of course they were skilled in all areas of drawing and painting, but when the great art workshops of the Renaissance period were in full swing it was the master painter who would often be the only artisan to put in the figures, leaving the rest of the composition to be completed by his pupils. So be prepared for the most interesting and most difficult stage in your drawing career but dont feel too daunted. I have found in many years of teaching that anyone can learn to draw anything competently, with the combination of a certain amount of hard work and the desire to achieve success.

The aim of this book is to explore all the practices necessary to achieve a good level of drawing of the human figure. I shall first look at how the human body is formed, from its skeleton the scaffolding that all figures are based on down to the details of the limbs, the torso, the hands and feet and the head. It is always useful to have some idea as to the body formation beneath the skin, and some knowledge of how the muscles wrap around the bone structure and each other is of great use when you look at the shapes on the surface of the body. Without any knowledge of the underlying structure it is much harder to make sense of the bumps and furrows that are visible.

I shall also look at the balance of the limbs when the body is in motion, and how the artist can produce the effect of movements that appear natural and convincing to the viewer of the picture.

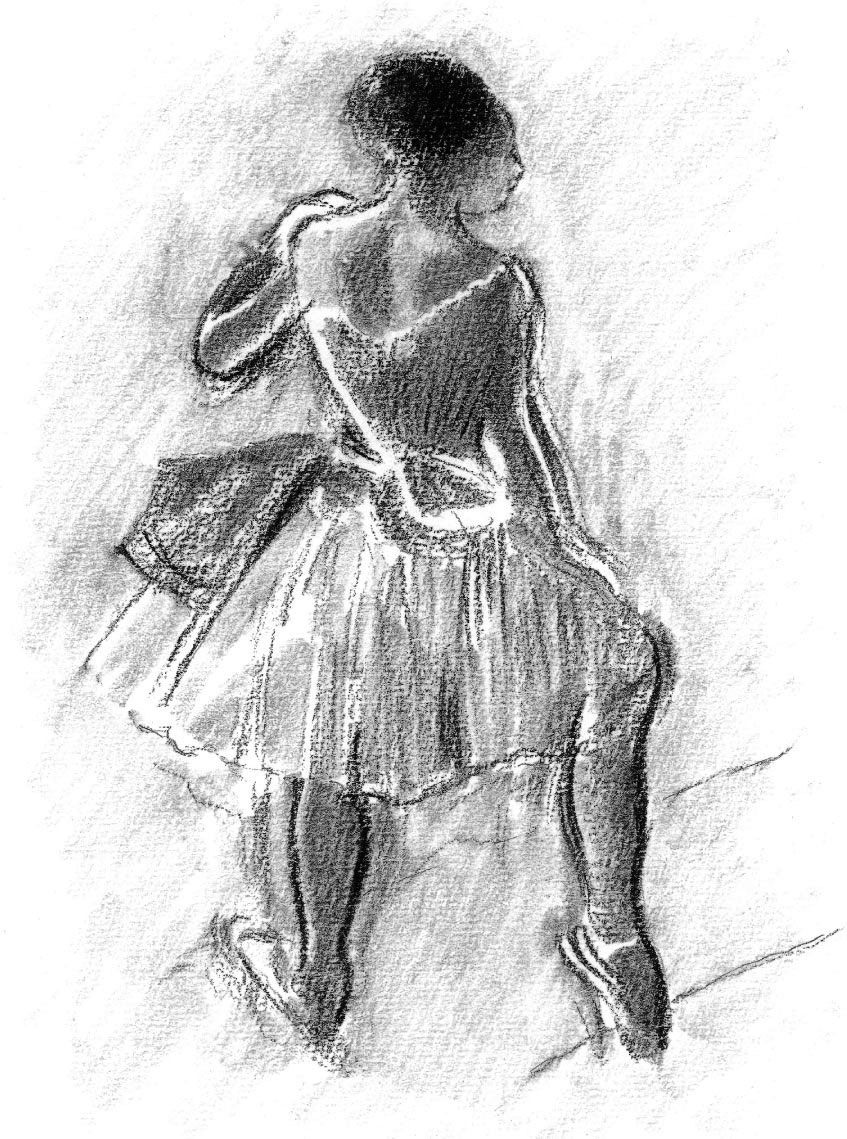

The techniques of drawing will also be examined, and the different ways in which artists have made efforts to show us how the human figure can be portrayed, from the most detailed to the most expressive. The book also includes a look at the ways that clothing helps to convince the viewer that there is a solid form under the surface material. Of course this book does not pretend to be exhaustive, as figure drawing has been developed and explored over centuries as artists sought new ways of portraying the human form. Nevertheless, enjoy this foray into the challenging but fulfilling task of portraying the human figure, and revel in the development of your own ability as an artist.

First Steps

The first section of this book explores the basic physiology of the human body, looking at the proportions, the structure and the obvious variations between male and female, child and adult. To draw the human figure successfully it is essential to have some acquaintance with what lies beneath the skin, for if you lack that your drawing will at best have a superficial slickness and at worse will not be at all convincing.

Proportions of the human figure

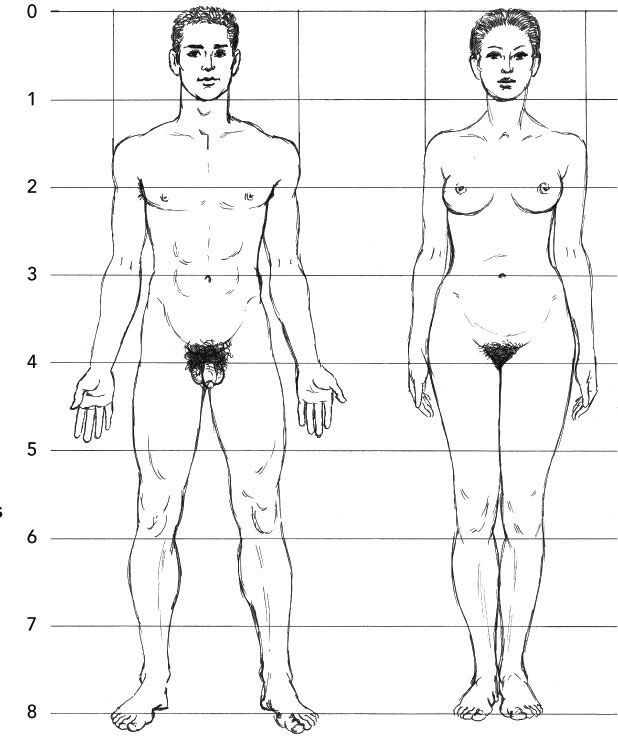

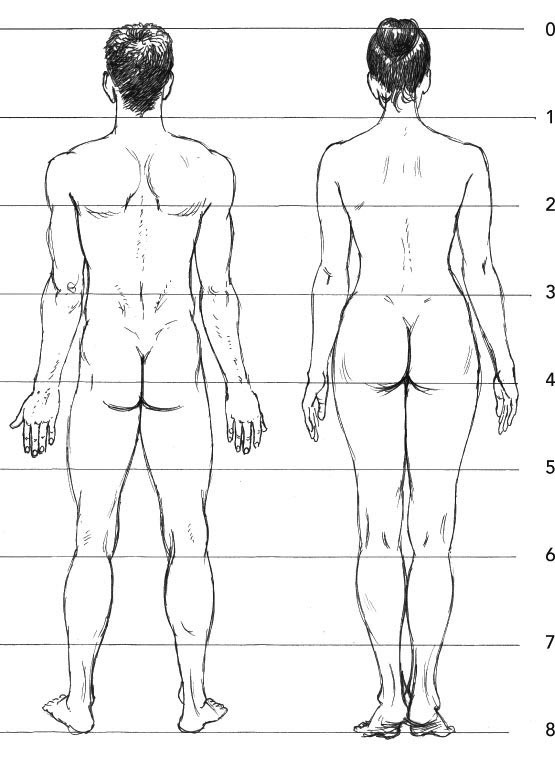

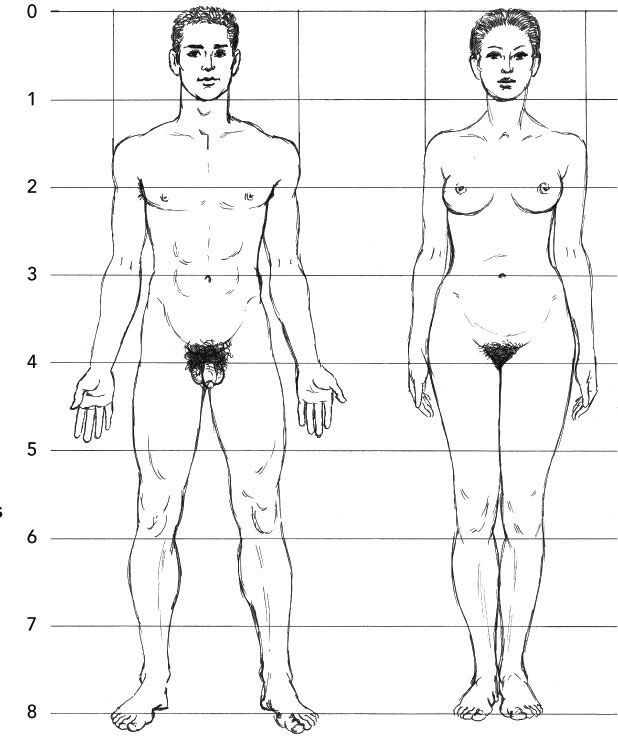

Here I have drawn a front view and a back view of the male and female body. The two sexes are drawn to the same scale because I wanted to show how their proportions are very similar in relation to the head measurement. Generally, the female body is slightly smaller and finer in structure than that of a male, but of course sizes differ so much that you will have to use your powers of observation when drawing any individual.

These drawings assume the male and female are both exactly the same height, with both sexes having a height of eight times the length of their head. This means that the centre of the total height comes at the base of the pubis, so that the torso and head are the upper half of this measure, and the legs account for the lower half. Note where the other units of head length are placed, for example the second unit is at the armpits. This is a useful scale to help you get started.

This is perhaps the most academic part of the book, but dont be tempted to skip the diagrams to get on quickly to drawing the whole figure. Putting in the groundwork at this stage will make your figures look more solid and more real, and will make viewers see exactly the human quality you wish to portray. You probably will not remember all the scientific names any more than I do, but the effort to learn something about them is never wasted and, in my experience, often comes back to help you when you least expect it. When you come to draw the figure from life you may also wish to refer back to these diagrams to clarify in your own mind what you have actually seen and drawn.

These two examples are of the back view of the two people opposite, with healthy, athletic builds. The mans shoulders are wider than the womans and the womans hips are wider than the mans. This is, however, a classic proportion, and in real life people are often less perfectly formed. This is a good basic guide to the shape and proportion of the human body.

The mans neck is thicker in relation to his head while the female neck is more slender. Notice also that the female waist is narrower than the mans and the general effect of the female figure is smoother and softer than the mans more hard-looking frame. This is partly due to the extra layer of subcutaneous fat that exists in the female body: mostly the differences are connected with childbirth and child rearing; womens hips are broader than mens for this reason too.

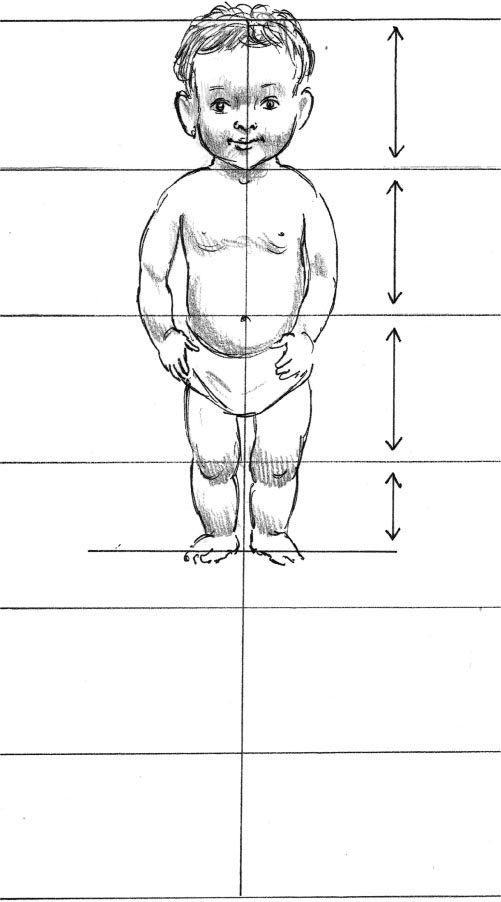

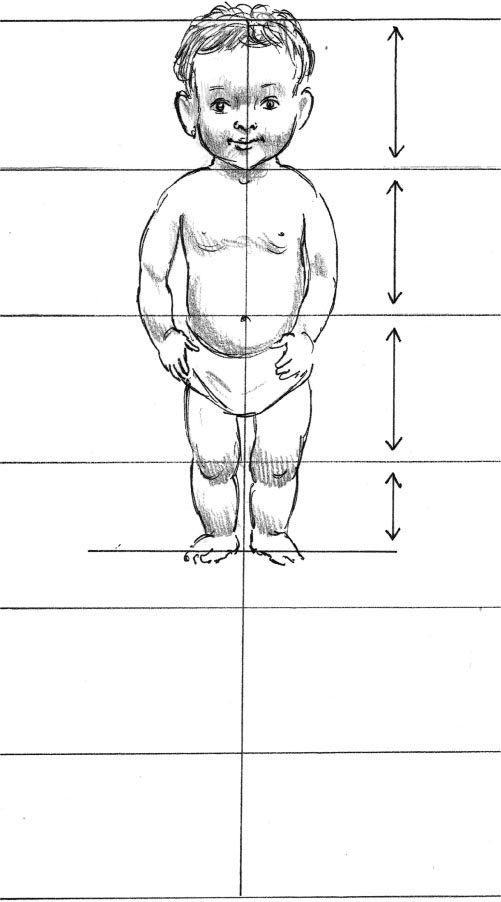

The proportions of childrens bodies change very rapidly and because children grow at very different speeds what is true of one child at a certain age may not always be so true of another. Consequently, the drawings here can only give a fairly average guide to childrens changes in proportion as they get older. The first thing of course is that the childs head is much smaller than an adults and only achieves adult size at around years old.

The thickness of childrens limbs varies enormously but often the most obvious difference between a child, an adolescent and an adult is that the limbs and body become more slender as part of the growing process. In some types of figure there is a tendency towards puppy fat which makes a youngster look softer and rounder. The differences between shoulder, hip and wrist width that you see between male and female adults are not so obvious in a young child, and boys and girls often look similar until they reach puberty.

At the beginning of life the head is much larger in proportion to the rest of the body than it will be later on. Here I have drawn a child of about months old, giving the sort of proportion you might find in a child of average growth. The height is only three and a half times the length of the head, which means that the proportions of the arms and legs are much smaller in comparison to those of an adult.