Women Writing Wonder

Series in Fairy-Tale Studies

General Editor

D ONALD H AASE , Wayne State University

A complete listing of the books in this series can be found online at wsupress.wayne.edu.

Women Writing Wonder

An Anthology of Subversive Nineteenth-Century British, French, and German Fairy Tales

Edited and Translated by

Julie L. J. Koehler, Shandi Lynne Wagner, Anne E. Duggan, and Adrion Dula

Wayne State University Press

Detroit

2021 by Wayne State University Press, Detroit, Michigan 48201. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without formal permission. Manufactured in the United States of America.

ISBN 978-0-8143-4501-6 (paperback)

ISBN 978-0-8143-4500-9 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-0-8143-4502-3 (e-book)

L IBRARY OF C ONGRESS C ONTROL N UMBER : 2021933977

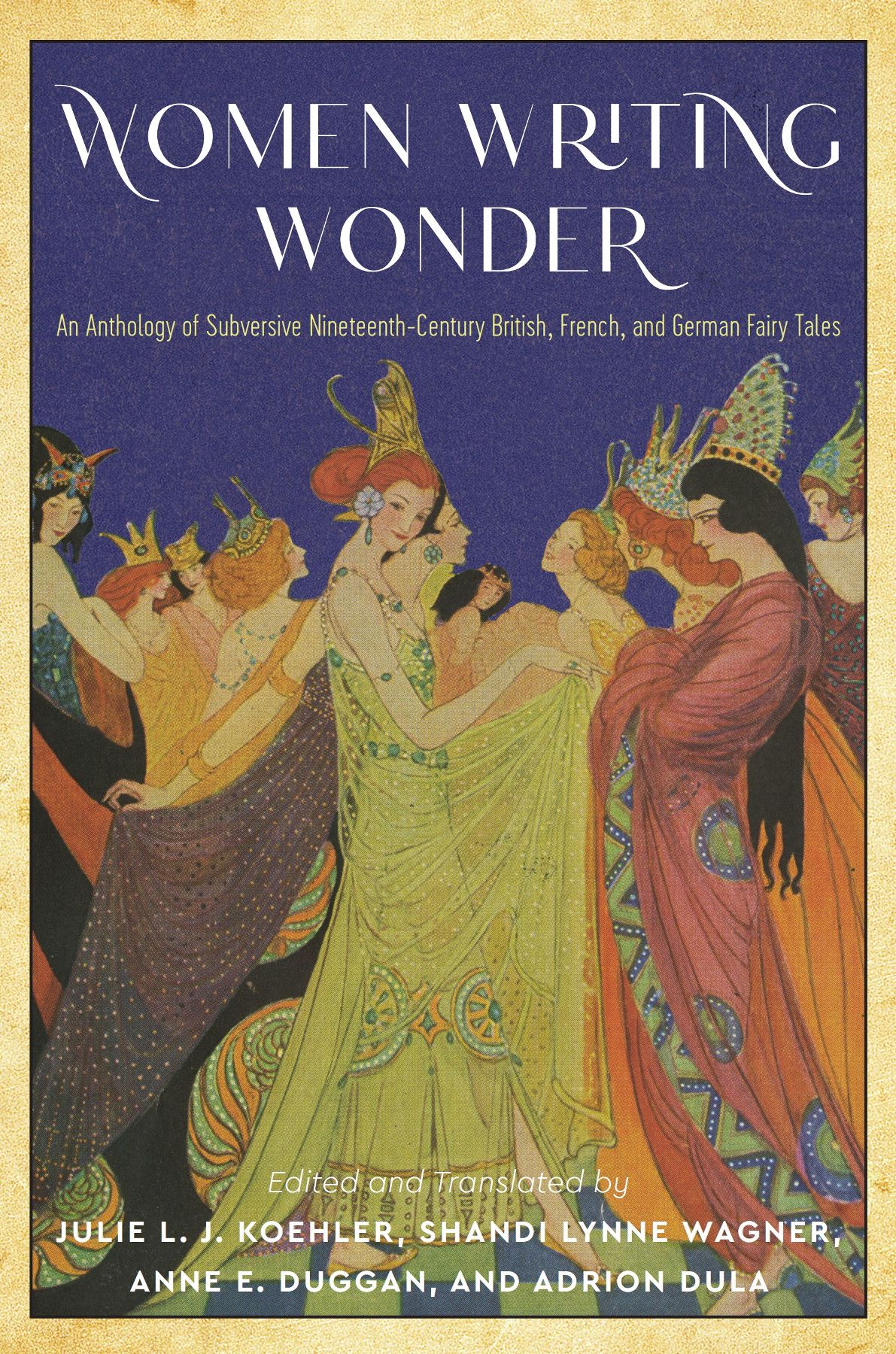

On cover: Elenore Abbott, The Shoes that Were Danced to Pieces, from Grimms Fairy Tales (New York: Charles Scribners Sons, 1920). Cover design by Laura Klynstra.

Published with the assistance of a fund established by Thelma Gray James of Wayne State University for the publication of folklore and English studies.

Wayne State University Press rests on Waawiyaataanong, also referred to as Detroit, the ancestral and contemporary homeland of the Three Fires Confederacy. These sovereign lands were granted by the Ojibwe, Odawa, Potawatomi, and Wyandot Nations, in 1807, through the Treaty of Detroit. Wayne State University Press affirms Indigenous sovereignty and honors all tribes with a connection to Detroit. With our Native neighbors, the press works to advance educational equity and promote a better future for the earth and all people.

Wayne State University Press

Leonard N. Simons Building

4809 Woodward Avenue

Detroit, Michigan 48201-1309

Visit us online at wsupress.wayne.edu

References to internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Wayne State University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Contents

This project grew out of a Wayne State University Humanities Center Working Group on the fairy tale, which included Anne Duggan, Adrion Dula, Abigail Heiniger, Julie L. J. Koehler, Janet Langlois, Lacey Skorepa, Shandi Lynne Wagner, and Adam Yerima. And we cant leave out Oakley (we miss you, Oakley!). Writing dissertations on nineteenth-century German and British authors, respectively, Julie and Shandi began to conceive of this project, and they deserve special recognition here. Then Anne and Adrion joined the project, which was supported in part by Wayne State Universitys Research Enhancement program from the Office of the Vice President for Research, which allowed the team to carry out archival research in the United States, France, and Germany. All the British texts have been transcribed and edited by Shandi, and translations bear the name of the translator; we thank Corrina Peet, who was our research assistant, for her work on some of the German translations. We also thank Walter Edwards, the director of the Humanities Center, who has given generous support to fairy-tale studies over the years. And finally, we would like to thank our families for all their support for this project.

Anne E. Duggan, Adrion Dula, Julie L. J. Koehler, and Shandi Lynne Wagner

There are many misconceptions about the fairy-tale genre today. Many people think of passive princesses la Disney, Charles Perrault, and select tales by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen, which have come to form the classical fairy-tale canon of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. This canon includes such tales as Beauty and the Beast, Cinderella, Hansel and Gretel, The Little Mermaid, Little Red Riding Hood, Puss-in-Boots, Sleeping Beauty, Rapunzel, and Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. With the exception of Beauty and the Beast, the canonical version of which was penned by Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont, the canon contains tales predominantly shaped by men, whether they are male-authored tales or tales that have a female source but were edited by men. These classical tales are taken to be representative of the fairy tale in general throughout the history of the genre in western Europe and the United States and Canada. Indeed, twentieth- and twenty-first-century authors and directors like Angela Carter, Margaret Atwood, Emma Donoghue, Amlie Nothomb, and Catherine Breillatto name a fewbase their revisionist fairy tales on this classical canon, often subverting the representations of gender and sexuality in a genre deemed inherently patriarchal and supposedly filled with passive heroines.

This conception of the genre lacks historical grounding and does not take into account the important role women writers have always played in the establishment of the fairy tale as a literary genre in western Europe. Since the 1980s, scholars such as Anne E. Duggan, Patricia Hannon, Elizabeth Wanning Harries, Lewis Seifert, and Jack Zipes have foregrounded the importance of the women fairy-tale writers of the 1690s in France, known as the conteuses, in the development of the genre. Marie-Catherine dAulnoy, Marie-Jeanne Lhritier, Henriette-Julie de Murat, and Catherine Bernardamong other women writerspenned tales that enjoyed as much popularity as those by Perrault, and they influenced eighteenth-century fairy-tale writers like Gabrielle-Suzanne de Villeneuve and Leprince de Beaumont. Indeed, dAulnoys tales remained part of the European fairy-tale canon well into the nineteenth century, influencing British, French, and German-language writers of tales. For instance, dAulnoys tales were widely adapted to the nineteenth-century British stage, as the work of Jennifer Schacker has aptly demonstrated.

While increasing attention has been paid to the 1690s French conteuses and the revisionist writers, such as Carter, Atwood, and Donoghue, women writing fairy tales in nineteenth-century Britain, France, and German states have not received the attention they deserve. Being attentive to writers like Flicit de Genlis, Bettina von Arnim, or Letitia Elizabeth Landon foregrounds a certain continuity and even a genealogy of women writing wonder, making us question conceptions of the fairy-tale canon as something stable or universal and leading us to rethink the ways in which gender and sexuality have been represented through the genre. Scholars have recognized the various models of female agency available in tales by the conteuses, the ways in which these women writers oftenbut not alwayschallenged patriarchal and unjust social and political structures. However, such questioning didnt simply end in the eighteenth century. Many women writers in France, the German states, and Britain took up the magic wand and continued producing tales that gave women a voice, and female characters agency, and that were also widely read by the general public.

Subverting Tradition

Fairy-tale scholars too often take as their point of departure, as noted above, what has become our twentieth- and twenty-first century notion of the genre, heavily influenced by the hegemony of Disney Studios, which significantly impacted the American and more generally Western canon of fairy tales. Subverting tales about passive heroines that have unfortunately become emblematic of the genre is not necessarily the subversion we are primarily concerned with here, but at times it can be. In fact, the tales we selected often subvert our twentieth- and twenty-first century expectations of the genre and its supposed preponderance of female passivity. Together, these tales do so by pointing out the complexity of the literary field in the nineteenth century, a field that can only be incomplete when so many women authors of fairy tales are ignored despite their popularity in the period. Subverting tradition can furthermore mean finding legacies that go beyond or undermine the unquestioned tradition or legacy of Perrault-Grimms-Andersen. Our corpus points, significantly, to the extensive legacy of dAulnoy found in the works of nineteenth-century women writers of fairy tales. Our writers thus draw from earlier tales by women authors that question everything from womens rights to the norms of the genre. They also often challenge fairy tales penned or edited by male writers in ways that undermine the gender norms propagated through them. Finally, the tradition these writers subvert can also refer to a more general questioning of gender norms that restrict female agency prevalent in nineteenth-century British, French, and German society, as well as the problematizing of class and even race issues in postrevolutionary Europe.

Next page