Copyright 2017 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

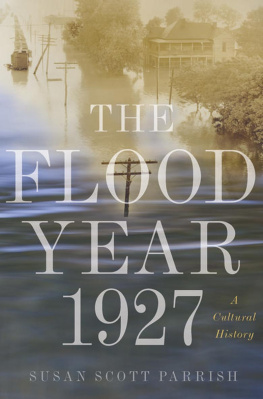

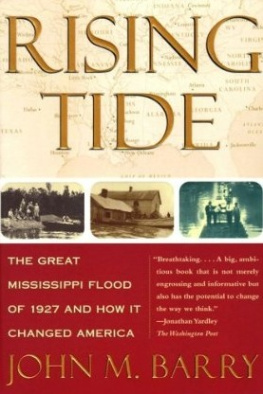

Jacket photograph: Rolling Fork, Miss. 5-2-27, flood water covers streets and railroad tracks, railroad cars sit on tracks. Rolling Fork, MS, 1927 Flood Photograph Collection, courtesy of Mississippi Department of Archives and History. Image of ripples courtesy of Shutterstock.

All Rights Reserved

Owing to limitations of space, all acknowledgments for permission to reprint previously published and unpublished material can be found on , which is an extension of this copyright page.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Parrish, Susan Scott, author.

Title: The flood year 1927 : a cultural history / Susan Scott Parrish.

Description: Princeton : Princeton University Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016009841 | ISBN 9780691168838 (cloth)

Subjects: LCSH: FloodsMississippi River ValleyHistory20th century. | Disaster reliefMississippi River ValleyHistory20th century. | Mississippi River ValleySocial conditions20th century. | Mississippi River ValleyHistory1865-

Classification: LCC F354 .P27 2017 | DDC 977/.043dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016009841

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Minion Pro, Monotype Modern Std and John Sans White Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Introduction

One morning during the first week of May 1927, a publicist working for the American Red Cross boarded a small navy sea plane in Memphis and, as the sun rose, flew south along the Mississippi River to the city of Greenville. En route, from a vantage of three thousand feet, Taylor, the publicist, took in what he called one of the most overwhelming tragedies nature has ever enacted. A story in which nature had been the protagonist, and the antagonist, was turning ineluctably into a story about humans.

Since the break at Mounds Landing, Taylor had been holed up in Red Cross relief headquarters in Memphis, doing his part in what he saw as a tremendous

But Taylor had yet to see the flood itself. That is what he intended to do on this early May morning. Flying south from Memphis, looking down from the sky, he began to notice little crowded islands of refugees, one full of animals marooned and doomed and surrounded by the carcasses of those that had already drowned. On a different islandlikely a mound constructed for flood seasons by ancient inhabitants of the valley long before the arrival of Europeanshe made out human families but couldnt tell whether their arm gestures were signals of distress. All around these islands, he saw nothing but opaque brown water. The whole scene, it seems, was still a bit abstract.

Soon enough, the pilot landed the plane in the water just off of Greenvilles levee, a sliver of artificial land eight miles long with a crown only eight feet wide that had, in the past few days, become a precarious city of thirteen thousand.

and while they wanted to understand better the geography and the human toll of the disaster, this marooned population wanted nonetheless to participate in the nations, and the worlds, virtual witnessing of a signal technological achievement. Taylor had seen this crowd as a mass of bodies and bodily needs. He had not imagined them as consumers of globally significant information or as part of a contemporary public. Less still did he imagine this crowdand crowds like them throughout the Deltaas poised to produce and disseminate meaning out of their experience. But that was exactly what happened in the days, months, and years to come.

If Lindberghs solo flight, mediated at a distance for a global audience, was one scenario of the modern, this haphazardly amassed population at a Red Cross camp was another. When we think about early twentieth-century catastrophes, we typically consider World War I, the financial collapse of 1929 along with the Great Depression, and the rise of fascism and genocide in Europe and the Near East. These have represented, and continue in our historical memory to represent, key problems of the modern age: mechanized combat and slaughter, unrestrained speculative capitalism, totalitarian governments, and the unstoppable global extension of crises. My conviction is that we are now prepared to see in this 1927 environmental disaster another signal, and abiding, problem of modern life. The Flood Year 1927 brings eco-catastrophe into our discussions of modernity, its experiences, and its cultures. Rather than a blow-by-blow narrative of the event itselfa typical feature of disaster historiographymy book explores how this disaster took on form and meaning as it was nationally and internationally represented across multiple media platforms, both while the flood moved inexorably southward and, subsequently, over the next two decades. I begin by looking at the social and environmental causes of the disaster, and by briefly describing the sociological certitudes of the 1920s into which it broke. I then investigate how this disaster went public, and made publics, as it was mediated through newspapers, radio, blues songs, and theater benefits. Finally, I look at how the flood comprises an importantbut until now underappreciatedchapter in the history of literary modernism.

My immediate goal is for readers to understand what a major cultural phenomenon this was. Historians have so far uncovered the details of what happened, especially out of sight in the upper echelons of local and federal government, to cause the flood to unfold the way it did. They show not what is abnormal or accidental but rather what has