CONTENTS

Guide

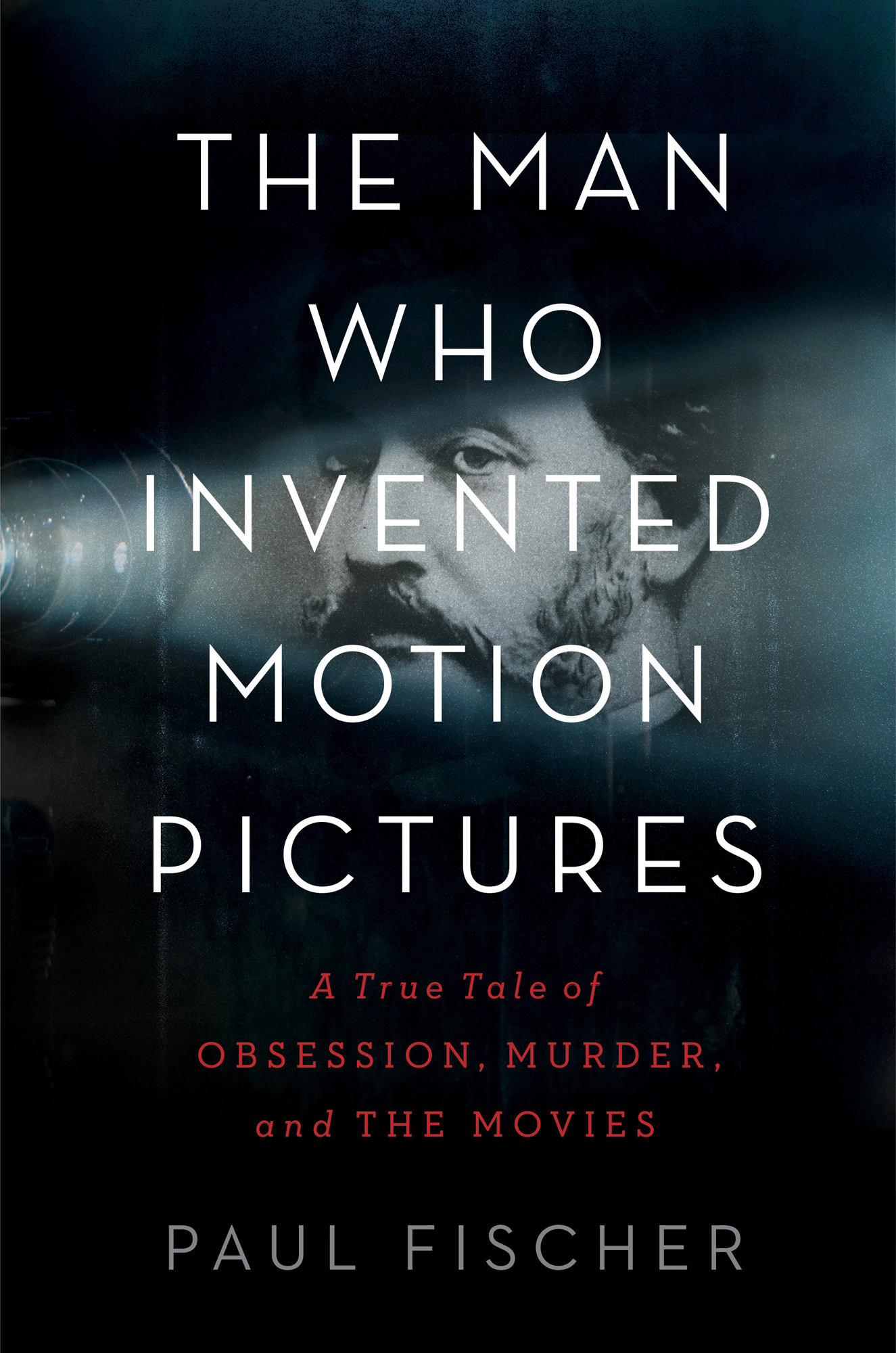

The Man Who Invented Motion Pictures

A True Tale of Obsession, Murder, and the Movies

Paul Fischer

For Crosby And for all those who continue to believe in the power of a bright screen in a dark room

&

In memory of Jacques Pfend, without whom this story could not have been told

AUTHORS NOTE

T here are two typical histories of the birth of the cinema. To the French, the brothers Auguste and Louis Lumire invented the movies one legendary night in December 1895, when they held the first-ever commercial showing of a motion picture in the basement of the Grand Caf, on Pariss Boulevard des Capucines. This was the evening, as the story goes, on which Parisiansstill lethargic from their Christmas feastswere sent shrieking out of the screening room by the Lumires Arrive dun Train en Gare de la Ciotat, in which a locomotive charges straight at the audience, and the evening on which men whose last names would become famousGaumont, Path, Mlisrealized that this would be the medium to make their fortunes. The aptly named Lumire brothers are emblems of French national pride, lionized in history books and the collective consciousness. After all, it is their invention, the Cinmatographe, that gives the entire medium its name.

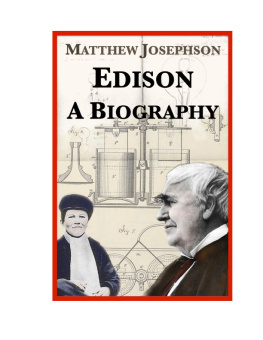

In the United States, it is another mythical figure of the nineteenth century who is credited with originating the next centurys defining medium. Thomas Edisoncelebrated by his countrymen in his own day as the Wizard of Menlo Parkfirst sold tickets to view moving pictures in a peep-show device, the Kinetoscope, in 1894. Edison, the self-made working-class genius from the Midwest, is as foundational to the modern American self-identity as the Lumires are to the French. Edison, he of the telegraph, the phonograph, and the light bulb. Edison, whose thousand patents and partial deafness and pithy quotes (I have not failedIve just found ten thousand ways that wont work; Genius is one percent inspiration and ninety-nine percent perspiration; Opportunity is missed by most people because it is dressed in overalls and looks like work) have become the stuff of legend. This is the person, American schoolchildren learn, who came up with the movies. His Kinetoscope was the first machine on which motion picturesa series of still photographs captured by a single lens, then shown at sufficient speed to create the illusion of motioncould be experienced by the public. So what if the Lumire brothers were the first to throw those moving pictures onto a screen? That, Edison contended, was not a matter of innovation but presentation.

Neither of these versions of history is the truth.

The following pages tell the true story of what happened before. Before Edisons Kinetoscope, and before the Cinmatographe. It is the story of Louis Le Prince, who, in 1888, made the worlds first motion pictureand then vanished.

Its a ghost story, a family saga, and an unsolved mystery. Its the story of an invention that, in the words of one of the first people to witness it in action, made death seem not so final, at the end of a century when humankind had already domesticated space, light, and time. Most of all, it is the story of one family, of a man who foresaw the world to come but did not live to see it materialize, and of the power of obsession and vision; of the previously impossible achievements they can make possibleand of the wreckage they leave behind when they betray you.

Key primary sources used in the writing of this book include the correspondence, manuscripts, and other documents in the Louis Le Prince Collection, held in the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society Collection at the University of Leeds Library; firsthand recollections in the possession of the descendants of Louis Le Prince, including unpublished memoirs by Lizzie and Adolphe Le Prince as well as sworn affidavits given by third-party witnesses and collaborators; objects, documentations, and artifacts, including Le Princes cameras and surviving pieces of film, held at the UK National Science and Media Museum in Bradford; historical records held at the West Yorkshire Archives; and materials in the Merritt Crawford Papers, collected between 1888 and 1942 and preserved at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Writing on Thomas Edison was supported by primary documents in the Thomas A. Edison Papers, curated and collected by Rutgers University; and original case files for the lawsuit in which the Le Princes participated were found at the National Archives at New York City. I am further indebted to over twenty-five years of research into Louis Le Princes life conducted in France by the historian Jacques Pfend, who generously opened his work to me. The usual sourcesincluding but not limited to census reports, immigration records, passenger and crew lists, city directories, patent records, newspapers of the period, and other official documentationwere used to corroborate timelines and events. Notes and a bibliography can be found at the back of this book. Any passage in quotation marks is a direct quote from a written account, diary, letter, memoir, court transcript, or contemporary document.

All remaining errors are mine alone.

Still from Roundhay Garden Scene. (Courtesy of Laurie Snyder / UK National Science and Media Museum, Bradford)

The image is a scratchy, faded monochrome, thick with thousands of microscopic silver crystals. As it movesbecause it is, in fact, a succession of images, transmuting stillness into movementthe picture skips and stutters. The edges of the image tear and fray, parallel ribbons of black rolling upward on either side, made uneven by wear and time.

Here is what the moving images show: On a flat, cold lawn, four human beings stroll in a loose circle. The young man in the foreground, dressed all in black, swings his arms wide in gleeful exaggeration, and the old man in the far corner imitates him, his coattails flapping behind him as he turns. There are two women between them, one young and one old, too, the first in a formal, tall hat and hooped dress, the second in a white bonnet and sober black frock.

All four of these people, as we watch them now, are long dead. They are ghosts. We are watching them because a man preserved them, by the alchemy of forces even he could not yet nameatoms, electromagnetic waves, and quantum energyin silver and light.

PROLOGUE

O n October 14, 1888in the fifty-first year of Queen Victorias reigna Frenchman by the name of Louis Le Prince, resident in Leeds, England, gathered his family on the front lawn of his in-laws country mansion for an experiment. The day was Sunday. The weather was bright and cold.

Le Prince was a tall, soft-spoken gentleman, six foot three in his stockings, at a time when the average man was nine inches shorter. The most striking aspect of Le Princes appearance at this timehe was by then forty-seven years oldwas his beard, white as snow and cut in the flamboyant style known as the Hulihee: long, fat muttonchops on the cheeks, combed outward and wavy, connected by a thick moustache, the chin shaved smooth. Though his appearance alone made him hard to forget, it was his character people found most memorable. He was a calm man, according to those who knew him. Frederic Mason, a mechanic who worked by Le Princes side for nearly three years, thought him in many ways a very extraordinary man, [even] apart from his inventive genius, which was undoubtedly great. Le Princes treatment of his men seemed a reflection of his feelings on the entire species: he was trusting, but exacting; passionate, but guided by reason; patient, though he held fast. He believed in progress. He had fought in uniform as a young manhad seen, up close, his own share of suffering and deathbut he hadnt lost his faith in the goodness of people. And he believed, firmly, that the new machine he had invented, which he would now demonstrate for his familya heavy box of Honduras mahogany balanced on a sturdy, four-legged standwould do more for human advancement and fellowship than any other invention before it.