The Byzantine Neighbourhood

The Byzantine Neighbourhood contributes to a new narrative regarding Byzantine cities through the adoption of a neighbourhood perspective. It offers a multidisciplinary investigation of the spatial and social practices that produced Byzantine concepts of neighbourhood and afforded dynamic interactions between different actors, elite and non-elite. Authors further consider neighbourhoods as political entities, examining how collectivities formed in Byzantine neighbourhoods translated into political action. By both acknowledging the unique position of Constantinople and giving serious attention to the varieties of provincial experience, the contributors consider regional factors (social, economic, and political) that formed the ties of local communities to the state and illuminate the mechanisms of empire. Beyond its Byzantine focus, this volume contributes to broader discussions of premodern urbanism by drawing attention to the spatial dimension of social life and highlighting the involvement of multiple agents in city-making.

Fotini Kondyli is Associate Professor of Byzantine Art and Archaeology at the University of Virginia.

Benjamin Anderson is Associate Professor of the History of Art and Classics at Cornell University.

Birmingham Byzantine and Ottoman Studies

General Editors

Leslie Brubaker

Rhoads Murphey

Rhoads Murphey

John Haldon

Birmingham Byzantine and Ottoman Studies is devoted to the history, culture and archaeology of the Byzantine and Ottoman worlds of the East Mediterranean region from the fifth to the twentieth century. It provides a forum for the publication of research completed by scholars from the Centre for Byzantine, Ottoman and Modern Greek Studies at the University of Birmingham, and those with similar research interests.

The Byzantine Neighbourhood

Urban Space and Political Action

Edited by Fotini Kondyli and Benjamin Anderson

After the Text

Byzantine Enquiries in Honour of Margaret Mullett

Edited by Liz James, Oliver Nicholson and Roger Scott

Centre for Byzantine, Ottoman and Modern Greek Studies

University of Birmingham

For a full list of titles in this series, please visit https://www.routledge.com/series/BBOS

First published 2022

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

605 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10158

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2022 selection and editorial matter, Fotini Kondyli and Benjamin Anderson; individual chapters, the contributors

The right of Fotini Kondyli and Benjamin Anderson to be identified as the authors of the editorial material, and of the authors for their individual chapters, has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record has been requested for this book

ISBN: 978-1-138-37106-4 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-032-07595-2 (pbk)

ISBN: 978-0-429-42777-0 (ebk)

DOI: 10.4324/9780429427770

Typeset in Times New Roman

by codeMantra

Birmingham Byzantine and Ottoman Studies Volume 31

Albrecht Berger

DOI: 10.4324/9780429427770-3

Research on neighbourhoods in Byzantium on the basis of literary texts suffers mainly from two problems: the scarcity of information on the one hand, and the lack of a consistent terminology on the other hand. If we have any information at all, it comes almost exclusively from Constantinople, which will therefore stand at the centre of my investigation.

Constantinople was, from its foundation to the end of the twelfth century, the capital of a great empire and the centre of imperial administration. A part of its population was of course formed by officials and military persons who were sent to the provinces and recalled, and by merchants who regularly left the city and travelled. Most inhabitants, however, lived there permanently and spent their life not just within the walls of Constantinople but within a spatially limited neighbourhood, where they worked, did their everyday shopping, and went to church.

Constantinople was founded by Constantine the Great in 324 and inaugurated in 330.1 Ancient Byzantium now formed its eastern-most part, and a big area, which was four or five times larger than the old Greek town, was added to the west. In the new part of the city, streets were laid out and terraces were built. New Constantinople was a planned city with straight streets and avenues,2 with public buildings and churches constructed at prominent places, probably following some more or less uniform urbanistic concept and it was also a city which was quickly filled by a very heterogenous population, even when it was still not much more than a monstrous construction site. It must have been a while before people felt comfortable there, that is, until the social and economic ties that develop with face-to-face interactions were established, and neighbourhoods formed where one could live in a more familiar, village-like environment.

My following remarks could not have been made without extensive reference to Paul Magdalinos recent article entitled Neighbourhoods in Byzantine Constantinople.3 I will try, however, to set other accents in my interpretation of the evidence, and will sometimes arrive at different conclusions.

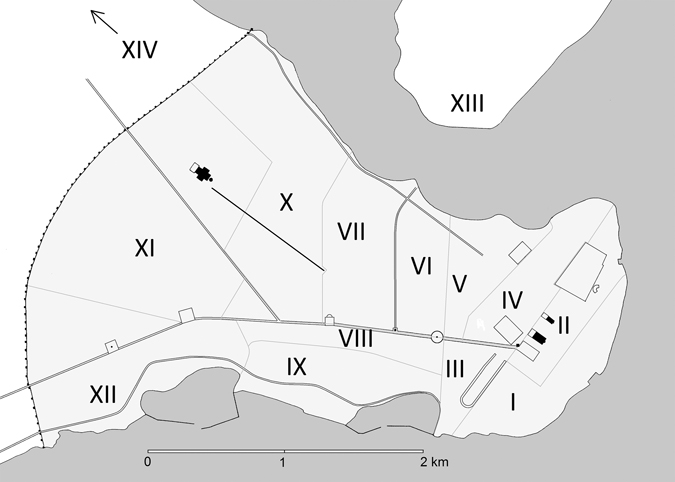

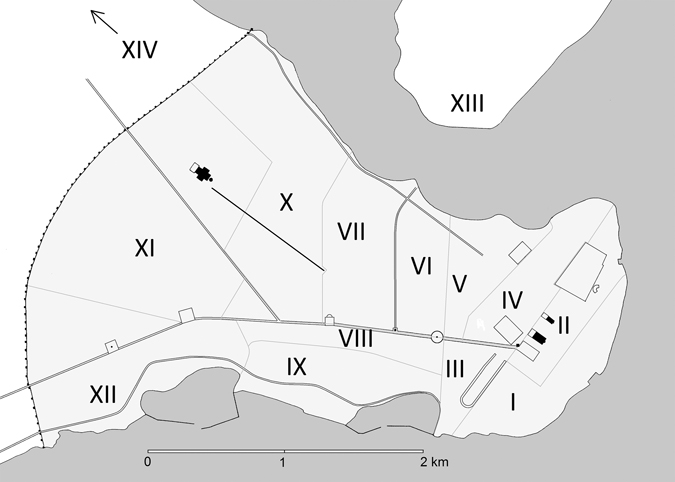

The basic text from which all our considerations must start is the so-called Notitia Urbis Constantinopolitanae, which was composed in Latin around 425 AD.4 It divides Constantinople into 14 regions (Figure 1.1) by analogy to Rome, lists its important buildings and monuments, and its 52 porticoed streets, 4,388 houses, and 322 vici (Table 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The regions of Constantinople. Image produced by the author.

The regions of the

Notitia Urbis Constantinopolitanae| Regions | Houses | vici |

|---|

| I | 118 | 29 |

| II | 98 | 34 |

| III | 94 | 7 |

| IV | 375 | 35 |

| V | 183 | 23 |

| VI | 484 | 22 |

| VII | 711 | 85 |

| VIII | 108 | 21 |

| IX | 117 | 16 |

| X | 636 | 20 |

| XI | 503 | 8 |