There were a number of seminal sources for the material in this book. In terms of printed material, the works of Kevin Danaher and Dith hgin deserve special mention. Thanks are also due to Eugene Costello for sharing his thoughts on booley houses and their music. To the library workers, both in the National Library and the Public Libraries, a special thank-you for helping me with sometimes long lists of requests. The staff at the Traditional Music Archive were also very helpful. I would also like to express my thanks to those people who helped me with copyrighted material: Tara Doyle of Dublin City Libraries, Tom Gillmor of the Mary Evans Picture Library, Ailbe van der Heide of The National Folklore Collection, UCD, Jonathan Williams of The Jonathan Williams Literary Agency and Alan Brenik of Carcanet Press.

Given that much of this book was researched in 2020, the ability to freely access the JSTOR collection of periodical articles proved invaluable. It could not have been written without that access, nor indeed without access to the invaluable National Folklore Collection. The material held there, collected from the schoolchildren of almost a hundred years ago, is truly a national treasure. I would like to thank the Director of the Collection, Crostir Mac Crthaigh for permission to quote from the Collection (a full list of the quotations used appear in the text credits at the end of the book).

In addition, I would also like to thank all at the OBrien Press for their hard work in putting this book together, especially Susan Houlden and Emma Byrne. Finally, I would like to thank family and friends for their encouragement and helpful suggestions, which ranged from discussions on the uses of red flannel to information on ancient mousetraps. Fidelma Massey, Tara Huellou-Meyler and Jacques Le Goff, thank you for allowing me to use your pictures and photographs. Jacques Le Goff, who had to listen to me through many a rant when things were not going well, deserves a very special thank-you for his support.

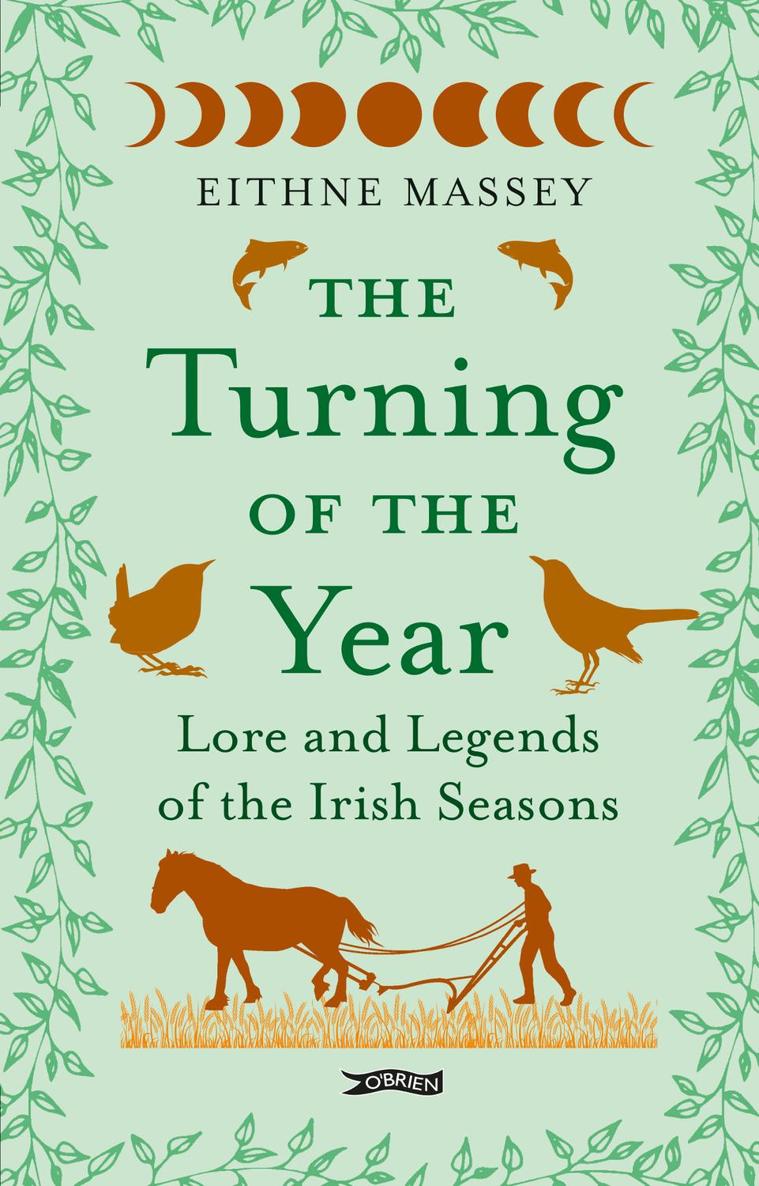

I n Ireland, the year begins in music. The Dagda, the great god of the ancient Celts, had a harp that was a living creature. We are told that when the Dagda played it, the year came forth from the music. Like a tune circling into itself, the seasons, marked by the changing weather and the changing face of the landscape, whirled along in a rhythmic progression. First the gold and red of dying leaves, then the dun of barren fields, then onwards to the whiteness of snowy hillsides and to the green of spring and summer forests. Forward to the gold of the harvest and then back again, to the deeper gold of autumn. The music the harp played was what the hero Fionn called the sweetest music in the world: the music of what happens. What is the music of what happens? Wolves howling, blackbirds singing, the small bleat of a newborn lamb sheltering on a February hillside or a girl calling her cows in from the pasture? It is all of this and more. It is the music that is played in time, as the seasons turn.

THE YEAR IN IRELAND

T he dying leaves of Samhain heralded the New Year in the Ireland of our ancestors, in celebrations beginning on the eve of the first of November. The Celts celebrated sacred days from twilight on the day before the festival, and similarly, the year began in the quiet of winter, where life can root and grow, waking to spring on the first of February, Imbolg. Summer was welcomed on the first of May, L Bealtaine, and autumn and harvest at Lughnasa, at the beginning of August. Samhain, Imbolg, Bealtaine and Lughnasa each of our seasons arrives several weeks earlier than is the norm in the rest of the world, for worldwide, the seasons are based on the movement of the sun, on its solstices and equinoxes in December, March, June and September.

In Ireland the division of the year is more closely based on agricultural activity, on the life cycles of the beasts that graze the land and the crops that grow on it. This division is seen in the earliest myths, such as in the story of the Second Battle of Moytura, which was fought between the Tuatha D Danaan and the Fomorians. The Fomorians had enslaved gods such as the D Danaan god Dagda, forcing him to dig ditches. When the Tuatha D Danaan defeated the Fomorians and captured their leader Bres, in return for his life he tells them the secrets of crop growing:

Spring for ploughing and sowing and the beginning of summer for maturing the strength of the grain, and the beginning of autumn for the full ripeness of the grain, and the reaping it. Winter for consuming it.

In this book, each section will include legends based on the lore, festivals or activities associated with the season. Like each place, each season in Ireland also has a story.

Each of the seasons has a different energy, and different tasks, pastimes, animals and plants associated with it. Each one has a different way of being, a different relationship with the earth. We mark these differences in every aspect of our lives, from the clothes we wear to the food we eat, in our celebrations and holidays and in the dark times when we trudge through each day, hoping that we are heading in the direction of the light. Seasons are also closely related to human cycles of growth, as singer/songwriter Yoko Ono put it succinctly in her album Season of Glass spring with innocence, summer with exuberance, autumn with reverence and winter with perseverance.

The Cycles of Nature and Their Rituals

In the past in Ireland, each turning point in the year was marked by a celebration which, over hundreds if not thousands of years, had become entrenched in the folk traditions of its people. The arrival of each season was marked by distinct customs and rituals.

It is these traditions that we will be looking at in this book. These folk rituals are more than just quaint observances and beliefs. For hundreds of years they brought the community together and acted as a form of social control. They also reflect the special relationship that both the individual and the community held with the natural world. Paying attention to the turning of the year and the natural cycles of the Earth can still be a way of experiencing a direct and powerful relationship with the world of nature.