Folktales from Africa:

THE BABOONS WHO WENT

THIS WAY AND THAT

More illustrated stories from

T HE G IRL W HO M ARRIED A L ION

For Finola O'Sullivan

CONTENTS

a cognizant original v5 release october 04 2010

These stories are rather different. They are not stories which one person has written they are stories which have been handed down from old people to young people over many, many years. Nobody knows who first told them; all we know is that they have been told for a very long time indeed.

The stories in this book are all from two countries in Africa Zimbabwe and Botswana. I collected some of them by talking to people and asking them to tell me the stories others were collected by other people who did the asking for me. Then I retold them in my own words, adding some descriptions to make the stories a little bit more vivid for those readers who do not know what Africa is like.

It is not easy to forget these stories they remain in the mind for a long time after we have come to their end. Why is this? I think that it is because they seem so strange to us when we first encounter them. They are about animals who can talk. They are about very peculiar things that happen. In the real world a hawk would not be a friend of a hen, and in the real world trees do not suddenly change into something quite different. But all this happens in these stories.

They are not just stories of magical events, though. Folktales are often meant to say something about how we should behave towards other people, and you will see that message in many of these stories. They show that selfish people will be caught out sooner or later. They show that we must help those around us. They also warn us to beware of tricksters.

When you have finished reading these stories, I hope that you may have found out something about Africa. Modern Africa, of course, is not like the Africa in these stories, but many of the traditions of the past still remain and many of the songs and stories too. The stories might help you to understand at least some of that traditional African culture.

Most of all, though, the stories are meant to be fun, and that, I hope, is what people will have when they read them.

Alexander McCall Smith

Edinburgh 2006

THE TALES

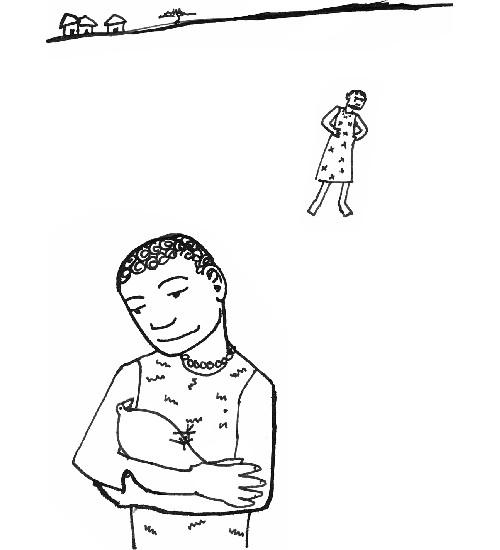

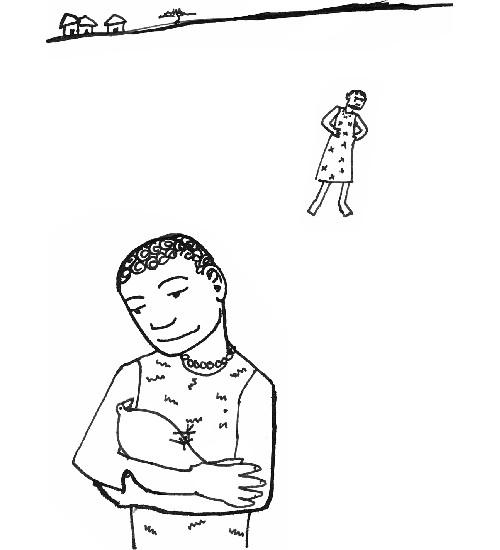

A rich man like Mzizi, who had many cattle, would normally be expected to have many children. Unhappily, his wife, Pitipiti, was unable to produce children. She consulted many people about this, but although she spent much on charms and medicines that would bring children, she remained barren.

Pitipiti loved her husband and it made her sad to see his affection for her vanishing as he waited for the birth of children. Eventually, when it was clear that she was not a woman for bearing a child, Pitipitis husband married another wife. Now he lived in the big kraal with his new young wife and Pitipiti heard much laughter coming from the new wifes hut. Soon there was a first child, and then another.

Pitipiti went to take gifts to the children, but she was rebuffed by the new wife.

For so many years Mzizi wasted his time with you, the new wife mocked. Now in just a short time I have given him children. We do not want your gifts.

She looked for signs in her husbands eyes of the love that he used to show for her, but all she saw was the pride that he felt on being the father of children. It was as if she no longer existed for him. Her heart cold within her, Pitipiti made her way back to her lonely hut and wept. What was there left for her to live for now her husband would not have her and her brothers were far away. She would have to continue living by herself and she wondered whether she would be able to bear such loneliness.

Some months later, Pitipiti was ploughing her fields when she heard a cackling noise coming from some bushes nearby. Halting the oxen, she crept over to the bushes and peered into them. There, hiding in the shade, was a guinea fowl. The guinea fowl saw her and cackled again.

I am very lonely, he said. Will you make me your child?

Pitipiti laughed. But I cannot have a guinea fowl for my child! she exclaimed. Everyone would laugh at me.

The guinea fowl seemed rather taken aback by this reply, but he did not give up.

Will you make me your child just at night? he asked. In the mornings I can leave your hut very early and nobody will know.

Pitipiti thought about this. Certainly this would be possible: if the guinea fowl was out of the hut by the time the sun rose, then nobody need know that she had adopted it. And it would be good, she thought, to have a child, even if it was really a guinea fowl.

Very well, she said, after a few moments reflection. You can be my child.

The guinea fowl was delighted and that evening, shortly after the sun had gone down, he came to Pitipitis hut. She welcomed him and made him an evening meal, just as any mother would do with her child. They were both very happy.

Still the new wife laughed at Pitipiti. Sometimes she would pass by Pitipitis fields and jeer at her, asking her why she grew crops if she had no mouths to feed. Pitipiti ignored these jibes, but inside her every one of them was like a small sharp spear that cuts and cuts.

The guinea fowl heard these taunts from a tree in which he was sitting, and he cackled with rage. For the new wife, though, these sounds were just the sound of a bird in a tree.

Mother, the guinea fowl asked that night. Why do you bear the insults of that other woman?

Pitipiti could think of no reply to this. In truth there was little that she could do. If she tried to chase away the new wife, then her husband would be angry with her and might send her away altogether. There was nothing she could do.

The bird, however, thought differently. He was not going to have his mother insulted in this way and the following day he rose early and flew to the highest tree that overlooked the fields of the new wife. There, as the sun rose, he called out a guinea fowl song:

Next page