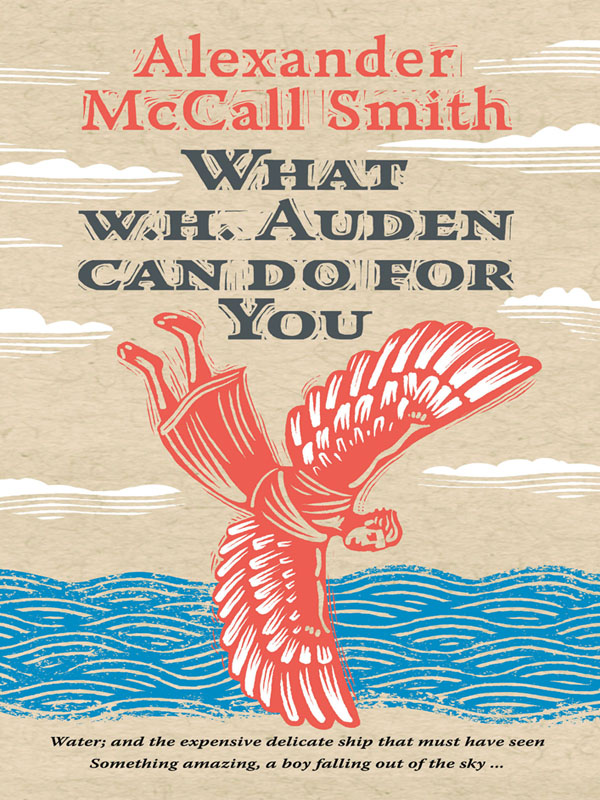

What W. H. Auden Can Do for You

Writers on Writers

Philip Lopate

Notes on Sontag

C. K. Williams

On Whitman

Michael Dirda

On Conan Doyle

Alexander McCall Smith

What W. H. Auden Can Do for You

Copyright 2013 by Alexander McCall Smith

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should

be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

Jacket illustration and design Iain McIntosh.

Lullaby (1937), copyright 1940 and renewed 1968 by W. H. Auden;

Funeral Blues, copyright 1940 and renewed 1968 by W. H. Auden;

excerpt from Muse des Beaux Arts (on jacket), copyright 1940 and

renewed 1968 by W. H. Auden, from Collected Poems of W. H. Auden

by W. H. Auden. Reprinted by permission of Random House, Inc. and

Curtis Brown, Ltd. Any third party use of this material, outside of this

publication, is prohibited. Interested parties must apply directly to

Random House, Inc. and Curtis Brown, Ltd. for permission.

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-14473-3

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013938077

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Calvert MT Std and Minion Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Authors Note

This book may be about a personal reaction to the work of W. H. Auden, but it nonetheless owes a great deal to the efforts of those scholars who have, over the years, created a significant body of critical literature dealing with Audens poetry and other writing. I have benefited greatly from the insights of those critics. Anyone writing about Auden, though, must owe a particular debt of gratitude to Professor Edward Mendelson, Audens literary executor and the author of two magnificent accounts of his work, Early Auden and Later Auden. Professor Mendelson generously read the manuscript of this book and noted several points that needed correction; responsibility for any remaining errors is, of course, entirely mine. I also enjoyed many conversations with Professor Mendelson over the years, including a number of such conversations in Scotland during the much-appreciated visits that he and his wife, Cheryl, made to us. I am most grateful to him for the light he sheds on even the most obscure of Audens lines; no poet, I think, could ever wish for a better guardian and exponent of his work than Professor Mendelson. I am also grateful to Professor Alan Jacobs for writing his wonderful book, What Became of Wystan? That book helped me greatly in understanding a number of aspects of the poets development.

What W. H. Auden Can Do for You

Love Illuminates Again

In the early months of 1940, with Europe embarking on what was to prove the greatest conflict of the twentieth century, W. H. Auden, a celebratedand controversialEnglish poet who had recently moved to the United States wrote a gravely beautiful poem. It took him some time, as this was no brief ode dashed off in a moment of inspirationthis was over one thousand lines, carefully and studiously constructed. Its title was New Year Letter, and it was addressed to Elizabeth Mayer, a refugee from the depredations of Nazi Germany, a translator, and a close friend. Like many of his works, this poem is conversational in tone but contains within it a complex skein of ideas about humanity and history, about art, civilization, and violence. At the end of the letter, though, there occur lines that are among the most beautiful he wrote. Addressing his friend, he draws attention to what she brings to the world through her therapeutic calling:

We fall down in the dance, we make

The old ridiculous mistake,

But always there are such as you

Forgiving, helping what we do.

O every day in sleep and labour

Our life and death are with our neighbour,

And love illuminates again

The city and the lions den,

The worlds great rage, the travel of young men.

These lines are about the person to whom the poem is addressed but when we read them today could be about Auden himself. He would never compliment himself, of course, but I believe that he is clearly one who is forgiving, who helps what we do, and if there is anything to be learned from his own work, it is precisely this message: that every day in sleep and labor, our life and death are indeed with our neighbor. And yes, in reading his poetry we see love illuminating our world. It is this view of Audens work that has prompted me to write an entirely personal book about the poet, about the influence he has had on my life, and about what this poet can mean for somebody who comes fresh to his work. I believe that if you read this poet, and think about what he has to say to you, then in a subtle but significant way you will be changed. This happened to me, and it can happen to you.

This small book does not purport to be a work of criticism. It does not claim to shed new light on a body of work that has already been extensively examined. It is simply an attempt to share an enthusiasm with others who may not have yet discovered, or may not have given much thought to the work of, Wystan Hugh Auden, generally known as W. H. Auden, the man whom many consider to be one of the greatest poets of the twentieth century. It is not a hagiographyit recognizes that Auden has been taken to task for trying to be too clever, for using words for effect and without real regard to their meaning, and for being juvenile. There are other charges against him: in particular, he was famously criticized by the poet Philip Larkin for turning his back on political and social engagement in favor of the self-indulgent and the frivolousa criticism that has lingered and is still occasionally encountered.

Some of these chargesparticularly the ones that accuse him of using language for effecthave some basis, but those of frivolity are certainly not justified. It is true that he deliberately turned his back on the leadership role to which English intellectuals had elected him in the years before the Second World Warthe Auden age, as some called itbut he by no means sought refuge in private reflection. His later poetry, although not overtly political, was very much concerned with the question of how we are to live and by no means evades profound issues. Of course some of the poems are better than others, and we can all agree that there are some that should never have seen the light of day, but what poet or novelist has not done at least something that is best forgotten? We fall down in the dance. Some writers have written whole books over which they, and sometimes their readers, would prefer to draw a veil. None of us is perfect, and Auden was a self-critical man who was in many cases his own severest judge, describing some of his poems as meretricious and worthless. Interestingly enough, even poems he rejected have, in the minds of his readers, survived this disowning. He wrote a poem called Spain that he considered dishonest, and yet it is still readand appreciatedin spite of its exclusion from the official canon. Similarly, September 1, 1939, has survived its authors judgment that it was a poem that he was ashamed to have written. This raises complex questions about aesthetics and the genuine. If a work of art gives pleasure in spite of the insincerityat the timeof its maker, then does that detract from its value?

Next page