About the Author

Veerle Poupeye is a Belgian Jamaican art historian, curator and critic. She was educated at the Universiteit Gent in Belgium and at Emory University in Atlanta. She served as the executive director of the National Gallery of Jamaica from 2009 to 2018, having previously worked there as a curator and museum educator. She has also served as coordinator of the visual arts programme of the MultiCare Foundation, a Jamaican inner-city development foundation, and as research fellow, lecturer and curator of the CAG[e] gallery at the Edna Manley College of the Visual and Performing Arts in Kingston. Her publications include Caribbean Art (first edition, 1998) and many book chapters, dictionary entries and exhibition catalogue essays on Jamaican and Caribbean art and culture. She has also contributed to journals such as Small Axe, Jamaica Journal, Caribbean Quarterly, Raw Vision and the New West Indian Guide.

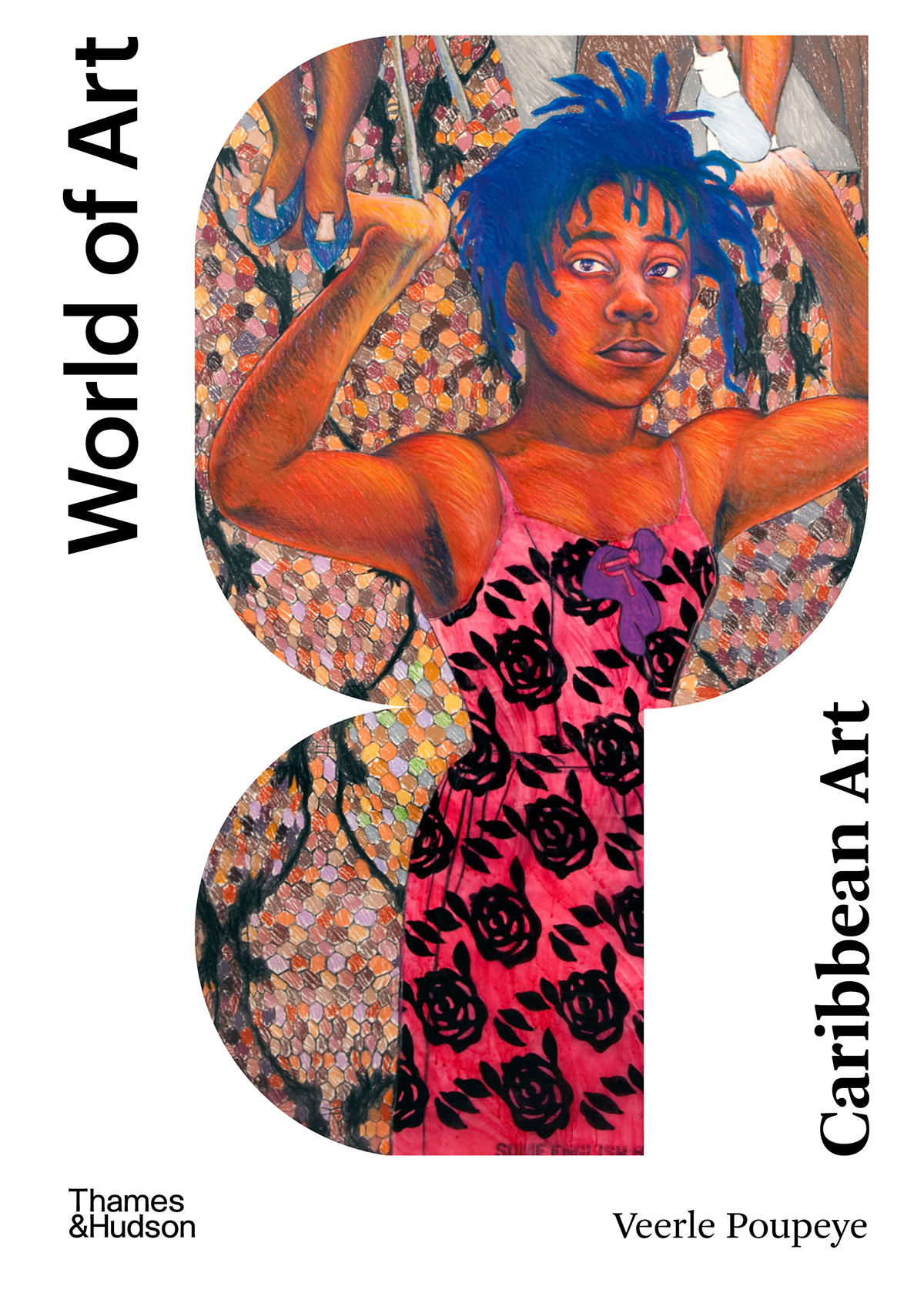

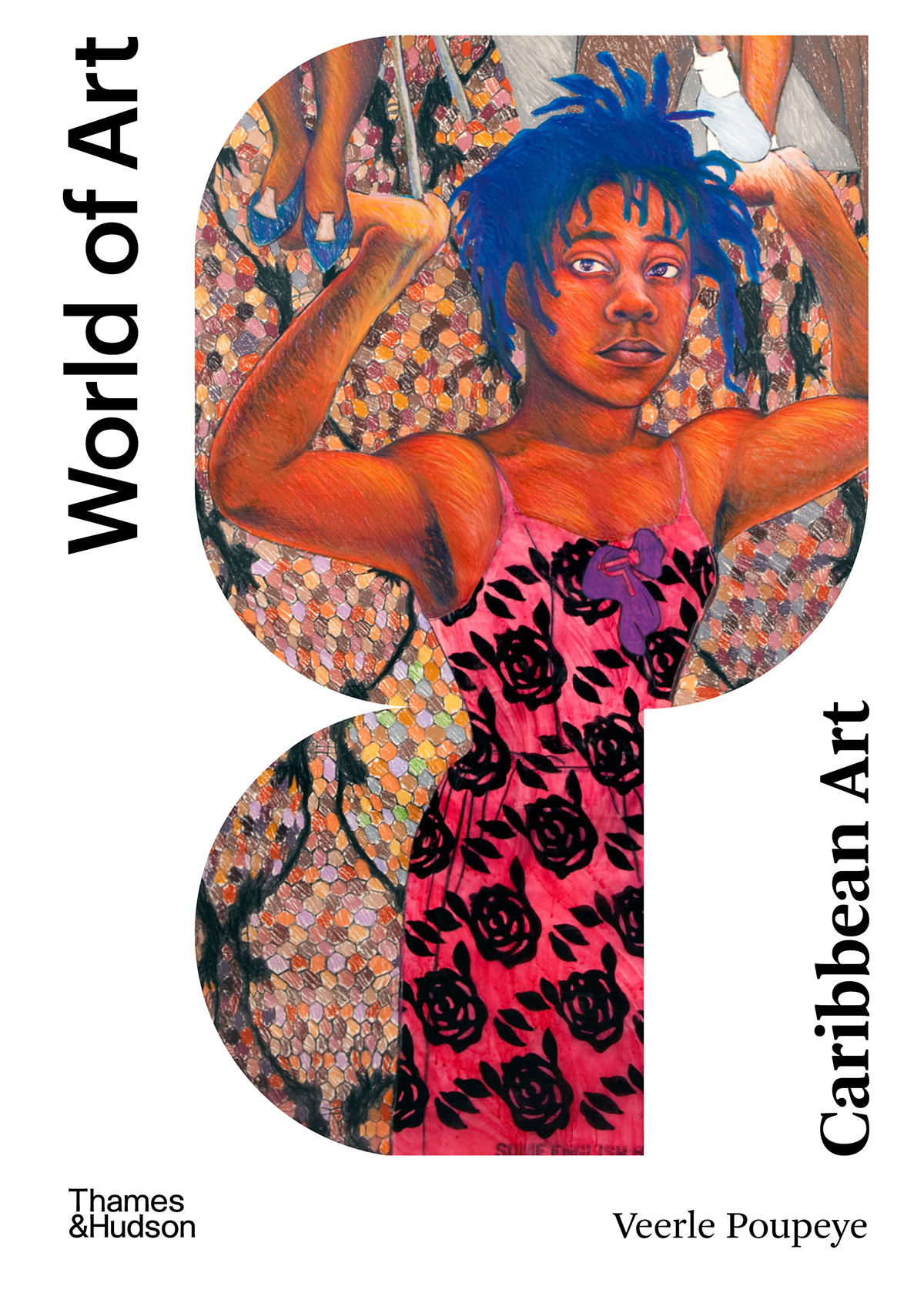

Colin Garland, In the Beautiful Caribbean, 1974 (detail)

Contents

When Caribbean Art was first published in 1998, a body of literature on the subject was already in existence, which consisted mainly of exhibition catalogues to which multiple authors had contributed most of the scholarship at that time was nationally focused. Caribbean Art was the first general survey of Caribbean art history written by a single author and it retains that distinction today, even though the literature, scholarship and criticism on the subject have grown tremendously. The book was, and still is, an ambitious undertaking and a perilous, high-stakes one at that, as presenting such a survey is inevitably couched in the highly contested and contentious politics of representation of the postcolonial Caribbean art world.

When the first edition of Caribbean Art appeared, its reception was mixed. Most published reviews welcomed what was deemed a valuable and indeed necessary addition to the literature, and the book has certainly made its contribution to the scholarship on its subject by serving as a reference and generating further research queries; but there were also negative responses, almost all of them from within the Caribbean. The book was scrutinized over national quota, over actual and perceived underlying assumptions and biases and, most of all, over which artists, and art works, were and were not included. The cautionary note in the introduction which asserted, perhaps naively, that the book was not meant to provide an encyclopaedic overview was clearly not sufficient to allay those concerns. Questions about who spoke, whose stories were being told and to whom the book was addressed, as well as whose interests were served by the narrative presented, were also raised. None of this was, with hindsight, surprising, nor was it undesirable, as such considerations have shaped the very course of art in the postcolonial Caribbean and similar questions have, in fact, been asked about all major publications and exhibitions on the subject.

There have also been significant, and related, changes in the politics and practice of the discipline of art history itself. The first edition of Caribbean Art was admittedly still torn between the genealogical thrust, evaluative vocabularies and canonical hierarchies of the old art history and the critical, sociological and self-reflexive focus of the new art history, which is rooted in cultural theory and criticism frameworks to which Caribbean intellectuals have, not coincidentally, contributed. Since then, there have been even more fundamental challenges to the ideological premises and institutions of conventional art-historical practice and their foundational connections to histories of colonialism, Eurocentricity and white supremacy. Simultaneously, the development of online resources and social media has created a new, democratized economy of knowledge and opinion about art and its representation which has added significantly to this line of questioning. Some have declared that the discipline of art history is now in terminal crisis and there is no clarity or consensus about the most productive alternatives or way forward.

How the stories about art in the colonial and postcolonial Caribbean are told is of particular importance in this context, but this offers no comfortable or correct answers to the question of how to write or revise a book such as Caribbean Art. An introductory survey for general readership, which is what Caribbean Art is, must provide a big picture overview that is painted in broad strokes. It must identify parallel developments and moments of convergence and exchange, shared ideas, concerns and contexts, as well as crucial departures, and it must illustrate these issues with instructive examples. It must have sufficient didactic clarity to be readable and useful, but it cannot provide the analytical or theoretical depth and nuance that is offered in more narrowly focused specialist monographs. It is difficult to avoid the mechanisms of canonical art history altogether in such a general publication.

Part of the problem is that it is easier to challenge and deconstruct dominant narratives and canons when these were already securely articulated and established. While there are well-established, and hotly contested, national narratives and canons in the many Caribbean territories, and artists from the Caribbean (such as Wifredo Lam and Jean-Michel Basquiat) who now hold a secure place in the global hierarchies of contemporary art, there are no established master narratives about Caribbean art in general against which one can argue and offer alternatives. What can and needs to be done, however, is to acknowledge and engage the politics and dynamics involved in producing art-historical narratives about Caribbean art in a critical, self-reflexive manner, and to make these considerations an active part of the discussion.

It was therefore decided to retain the general approach of the first edition, which had a hybrid chronological and thematic structure, and to revise and update the original chapters thoroughly, with the earlier-mentioned issues in mind. Two new chapters have furthermore been added that help to provide a more comprehensive picture. The first of these is on the public statues and monuments of the Caribbean, many of which date from the colonial era or represent colonial figures and values and have been contested accordingly a subject that has significant currency in the present, iconoclastic cultural moment. The second new chapter explores the role of tourism in Caribbean art. The Caribbean is one of the most tourism-dependent regions in the world and the intersections between art and tourism in the colonial and postcolonial period have been problematic and controversial, raising important and troubling questions about cultural representation.

This second edition of Caribbean Art is thus offered as one of many possible perspectives on its subject, a perspective that is wide-ranging, as a survey needs to be, but makes no claims to being definitive or complete. It is hoped that in its new, revised and expanded form the book will make a further contribution to the understanding of Caribbean and postcolonial art and its context, and that it will be as useful, engaging and indeed provocative to those who are not familiar with the subject as to those who are well-versed in it, in ways that invite productive conversation and encourage other readings on the subject.

Next page