To the memory of my dear parents, Jack and May Laverty; and for the three men in my life, Richard, Stephen and Peter

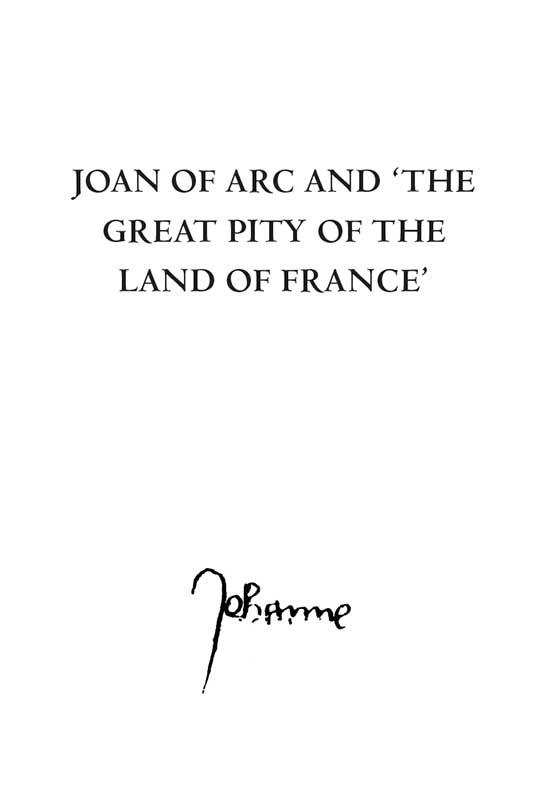

Page 1: Joan of Arcs signature.

Page 3: Statue of Joan of Arc outside the glise Saint-Augustin de Paris, 1919. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

First published 2017

Amberley Publishing

The Hill, Stroud

Gloucestershire, GL5 4EP

www.amberley-books.com

Copyright Moya Longstaffe, 2017

The right of Moya Longstaffe to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 9781445673042 (HARDBACK)

ISBN 9781445673059 (eBOOK)

Map design by Thomas Bohm, User design.

Typesetting and Origination by Amberley Publishing.

Printed in the UK.

Contents

Prologue

Joan: A Burning Question Still

Jeanne, toi qui as donn au monde la seule figure de victoire qui soit une figure de piti!

Andr Malraux, Rouen, 30 May 1964

On Wednesday, 21 February 1431, at 8 oclock in the morning, a girl of nineteen years of age was led into the chapel of the castle of Rouen, before a tribunal presided over by the portly Bishop of Beauvais and comprising no less that forty-two eminent theologians and canon lawyers of all ages, sitting in solemn array, leaning forward and gazing at her with intense curiosity, mingled in many cases with stern disapproval, dark suspicion, and occasionally perhaps even pity. She was dressed in plain and sombre male clothing, a belted knee-length tunic over the hose of a page, but she was of average height and build for a girl of her time, not at all the strapping hoyden they might have expected.

Who was this notorious and enigmatic prisoner, on trial for her life? What had brought her to this pass? We have no portrait of her, although we know that at least one did exist, and probably more. During her trial, on 3 March 1431, she mentions having once seen a portrait of herself, in the possession of a Scotsman. There were of course large numbers of Scots troops fighting as allies of the French. It showed me fully armed, she said. I was on my bended knee before the king, presenting him with letters. I have never seen nor had any other portraits made. However, she is certainly one of the best-documented figures in history. In the weighty volumes of the minutes of her trial in 1431 and the careful enquiry which was the Nullity hearings of 1452-6, every detail of her life, from childhood onwards, is recorded either in her own words or in the eyewitness accounts of her friends and her companions-in-arms. These documents and related ones were first collected together and published, in five hefty volumes, in the 1840s by the eminent historian Jules Quicherat, thus making possible for the first time a serious and informed study of her life and personality, four hundred years after her death. There are abundant other, less immediate, accounts of her drama to be found in the writings of the chroniclers and letter-writers of her time, much of which needs sifting and weighing. Yet despite this wealth of evidence, controversies have raged, historians have argued, painting conflicting portraits of her and the role she played on the international stage, ever since her brief and brilliant intervention in 1429 in the war between France, on the one hand, and England and its Burgundian allies on the other. Her time was short and she knew it, a little more than a year of warfare, then a year of captivity, finishing in her trial and terrible death at the stake on 31 May 1431.

Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini (later Pope Pius II), who was present at the negotiations for the Treaty of Arras in 1435, which effectively closed the bitter conflict with Burgundy and signalled the end of the English enterprise in France, wrote in his Memoirs that they were many conflicting opinions about Joan at the time. It is a great shame, wrote tienne Pasquier already in the late sixteenth century, for no-one ever came to the help of France so opportunely and with such success as that girl, and never was the memory of a woman so torn to shreds. Biographers have crossed swords furiously about her inspiration, each according to the personal conviction of the writer. Among the most celebrated of earlier historians we find Simon Luce, ascribing her visions to an imagination heightened by the episodes of war and the tribulations of her village, Henri Wallon dismissing such an argument and painting a much more peaceful picture of Joans youth, Anatole France classifying her among the numerous petty prophets and visionaries of the time with their crazy illusions, a thesis indignantly refuted by the Scottish writer Andrew Lang, and the learned Jesuit, Father Ayroles, championing the saint.

So it has continued to this day, each biographer striving for objectivity or grinding his or her own axe, perhaps subconsciously. She has been claimed as an icon by zealous combatants of every shade of opinion, clericals, anticlericals, nationalists, republicans, socialists, conspiracy theorists, feminists, far-rightists, loony-leftists, yesterdays communists, todays Front National (which, by claiming her as one of their own, has managed to damage her image more than any of the rest), old Uncle Tom Cobley and all. As Bernard Shaw said, in the prologue to his famous play, the question raised by Joans burning is a burning question still. And so it always will be, for she is for all of them a sign, but a sign of contradiction. A sign perhaps, but not a legend. There is no legend of Joan of Arc. For my part, I do not intend to study her as a sign, nor to use her as a cosh with which to batter anyone about the head, but as a person, a very human, vulnerable person, against the background of her own time.

No fantastic miracles were ascribed to her, such as were plentifully heaped by the excitable popular imagination of the day upon so many genuine or fraudulent or self-deceived visionaries. She was never said to have made corpses get up and walk to confession or to have made the sun rise three hours early, folk tales such as were told about Saint Colette of Corbie, her contemporary. Her achievements crowned human effort and courage on her own part and on the part of those with her: The soldiers will fight and God will give the victory, was her motto. The walls of Jericho (or any other town) did not obligingly fall down before her. The nineteenth-century historian Vallet de Viriville, sums it well up when he writes, The Maid appears as a profoundly religious young woman of outstanding piety, but in no way a mystic or miracle-worker. Her history is recorded in sober factual detail both by contemporary chroniclers and above all in the legal documents of the two trials of 1431 and 1456, where we can read it and make up our own minds. In this book, I intend to put before the reader the essential material from those documents and from contemporary records and chronicles.