GLACIER

The Earth series traces the historical significance and cultural history of natural phenomena. Written by experts who are passionate about their subject, titles in the series bring together science, art, literature, mythology, religion and popular culture, exploring and explaining the planet we inhabit in new and exciting ways.

Series editor: Daniel Allen

In the same series

Air Peter Adey

Cave Ralph Crane and Lisa Fletcher

Clouds Richard Hamblyn

Comets P. Andrew Karam

Desert Roslynn D. Haynes

Earthquake Andrew Robinson

Fire Stephen J. Pyne

Flood John Withington

Glacier Peter G. Knight

Gold Rebecca Zorach and Michael W. Phillips Jr

Ice Klaus Dodds

Islands Stephen A. Royle

Lightning Derek M. Elsom

Meteorite Maria Golia

Moon Edgar Williams

Mountain Veronica della Dora

North Pole Michael Bravo

Rainbows Daniel MacCannell

Silver Lindsay Shen

South Pole Elizabeth Leane

Storm John Withington

Swamp Anthony Wilson

Tsunami Richard Hamblyn

Volcano James Hamilton

Water Veronica Strang

Waterfall Brian J. Hudson

Glacier

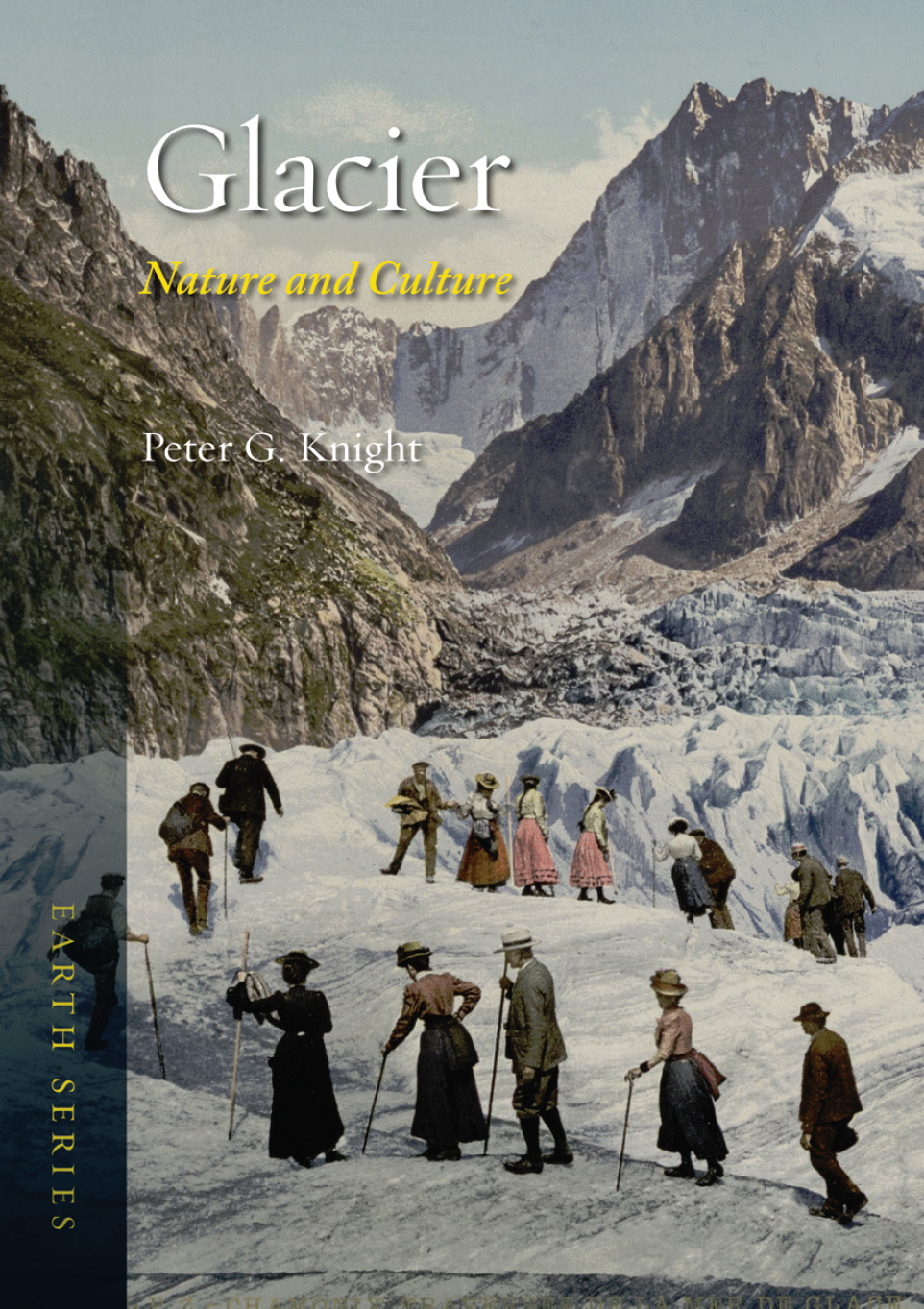

Peter G. Knight

REAKTION BOOKS

This book is for C. G. Knight,

because I think he would have particularly liked this one

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

Unit 32, Waterside

4448 Wharf Road

London N1 7UX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2019

Copyright Peter G. Knight 2019

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page References in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index Match the Printed Edition of this Book.

Printed and bound in China

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN 978 1 78914 169 6

CONTENTS

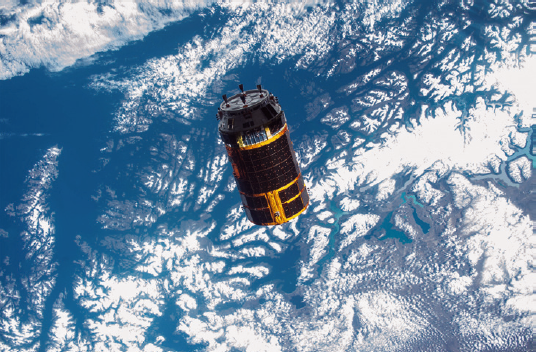

A mountain glacier descending into Glacier Bay, Alaska.

Preface

There are many ways of looking at the world, and what we see depends on how we choose to look. The artist, the scientist, the politician, the engineer: we each have different points of view, and so we each see different things. There are many books about glaciers that focus on glacier dynamics, climate change, geomorphology, physics, hydrology and so on. At first glance the physical sciences seem to have a virtual monopoly. This book does address some of that basic glacier science, including the history of the ice ages, ways in which glaciers create landscapes, and the role of glaciers in the big global system of climate change and sea-level rise, but this is not enough. Marcel Proust, in his novel In Search of Lost Time, wrote that the only true voyage of discovery consists not in exploring new places but in seeing through new eyes. This book looks at glaciers through the eyes of explorers, politicians, artists, poets and storytellers as well as scientists. We learn by seeing things in different contexts, and we see more when we see from different perspectives.

Human life has developed in an unusual period of Earths history: part of the 15 per cent or so of geological time during which glaciers have existed. But it is less than two hundred years since it was widely understood that glaciers come and go, that they were once more extensive than they are now, and that many of them are disappearing in response to human impact on the environment. This realization was a paradigm shift both in science and in our cultural relationship with nature. We can call it the glacial turn: we live not only in a physical ice age, in which glaciers affect the landscape, but in a cultural ice age, in which our understanding of how glaciers fit into the planets life affects our whole view of the world and our place within it.

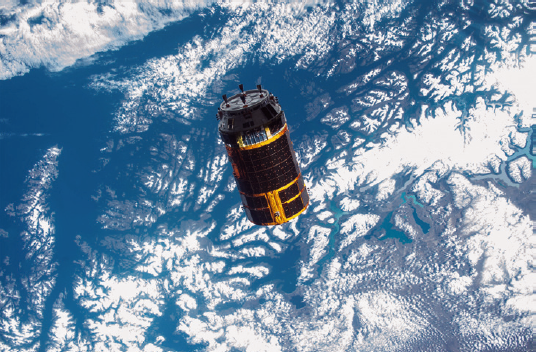

How we see glaciers depends on how we look at them, and our points of view have changed over time. This photo, taken from the International Space Station in September 2015, shows the glaciers of the Torres del Paine National Park in southern Chile, and a space cargo vehicle on its return journey to Earth.

Increasingly, over the last two hundred years, glaciers have affected culture, spirituality and our view of ourselves. Those physical and cultural ice ages are reflected not only in our science, our environmental future and our economics, but in our art and our adventures. For readers who know little or nothing about glaciers this book provides a broad introduction ranging from the science of how glaciers work to the way that glaciers have featured in art and in the human imagination. For people who already know something about glaciers, I hope the book will offer some new points of view.

Ways of Thinking about Glaciers

A perennial mass of ice, and possibly firn and snow, originating on the land surface by the recrystallization of snow or other forms of solid precipitation and showing evidence of past or present flow.

Today, from a distance, I saw you

walking away, and without a sound

the glittering face of a glacier

slid into the sea.

Precisely defined for the scientist, a metaphor and an icon for the poet, glaciers for each of us have their own place in our view of the world.

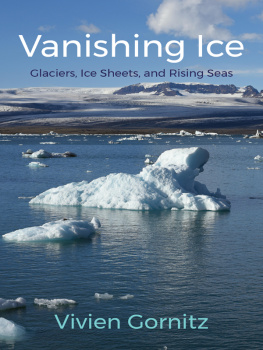

Human life has developed in an unusual period of Earths history: a period in which there are glaciers. Of the history of the planet, glaciers have been here, on and off, for only about 15 per cent of the time, but they have been here throughout the 2 million years of human history and prehistory. However, only for the last century have we lived in an age in which the importance of glaciers has been acknowledged. It is less than two hundred years since the idea was first widely accepted that ice ages come and go, and that glaciers used to cover much more of the Earths surface than they do now. We have only just noticed that we are living in a glacial period. We live now, for the first time, in a cultural ice age as well as a physical one. Few of us consciously place glacier at the heart of our view of the world but we do now appreciate the key role of glaciers both in the planets past creating the landscapes that surround us and in its future, as major players in the unfolding drama of climate change. But at the same time that we noticed glaciers we also realized that the physical ice age may be coming to an end, that we are losing the glaciers, and that it may be our fault that we are losing them so fast.

Because we recognize the importance of glaciers in the global system we now have a particular view of the world, different from that of the generations before us. In glaciers we recognize natures fragility, complexity, majesty, ephemerality, vastness, beauty, terror: in glaciers we see the sublime. Each of us is also touched by them very directly on a practical day to day level, wherever on the planet we live. Glaciers created my local English landscape, determining the nature of the soil and of the crops that grow here, but they also control the atmospheric and ocean circulations that drive weather systems across the globe. They influence sea level in every ocean, and they supply drinking and irrigation water to millions of people. Glaciers are not remote: they reach out to touch everything, everywhere. On the other hand, especially to lowland, mid-latitude city dwellers, the glacier is an alien creature whose name conjures images of wilderness, frozen wasteland and polar desert.