I am immensely grateful to WN Herbert and Tina Gharavi who played an important role in shaping the study which was later transformed into the present book. Thanks are also due to the following faculty at Newcastle University who read part of my material in different stages: Jackie Kay, Peter Reynolds, Margaret Wilkinson, Laura Fish, Andrew Shail, and Cynthia Fuller. Their feedback was always encouraging and extremely helpful.

I would also like to thank Sean OBrien and Ahmad Karimi Hakkak for their support and in-depth criticism of the manuscript in its early stage.

It was a pleasure and a privilege working with editors at I. B. Tauris; Sarvat Hasin, Sophie Rudland, and Rory Gormley to whom I would like to extend my heartfelt thanks and gratitude. The three anonymous reviewers offered extremely helpful suggestions. I would like to extend my appreciation for helping me improve the quality of this book.

My lovely wife, Vida, and my children Behafarid, Mehrafarid and Bardia have been a source of extraordinary joy and strength during the years I worked on this project. I know I should have spent much more time with them. They are my guiding light and my endless treasure of happiness and I thank them for their understanding and love.

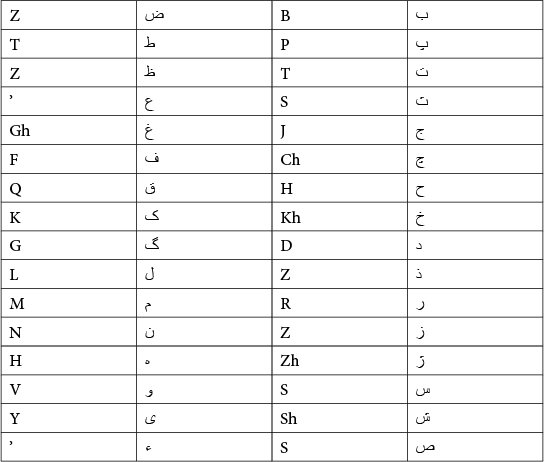

I have used the transliteration scheme of the International Society for Iranian Studies as described below:

Consonants

Vowels

| Short | Long | Diphthongs |

| a (as in ashk) | or (as in ensn or b) |

| e (as in fekr) | i (as in melli) | ey (as in Teymur) |

| o (as in pol) | u (as in Tus) | ow (as in rowshan) |

Other rules:

The ezafeh is written as -e after consonants, e.g. ketb-e and as -ye after vowels (and silent final h), e.g. dary-ye and khneh-ye

The silent final h is written, e.g. Dowleh

The tashdid is represented by a doubling of the letter, e.g. takhassos

The plural h should be added to the singular as in dast-h

Proper names of persons and places have been recorded based on the most common spelling which may or may not comply with the above transliteration scheme.

All translations are mine unless noted otherwise.

Sara and I were the top students in year three in Manuchehri Primary School. We enjoyed constant rivalry and each claimed to be brighter than the other. We had a small library at school one shelf of childrens books and Sara was in charge of it. I wanted to borrow a book and chose Babrh-ye Gharibeh (The Foreign Tigers). She asked me the name of the book to fill in the borrowing card. I read it wrongly as Babarh-ye Gharibeh, which is a meaningless phrase. She ridiculed me and I was really embarrassed. The following year, I wanted to borrow the same book for my cousin, however, it was no longer available. So I asked my teacher, Mr Afshang, about it. He said: We removed that book because it was published by the Farah Foundation and encouraged the spirit of surrender to the strangers. Such books are not good for the Revolution kids. Revolution was in its stormy days and even our remote village was burning with the fever. Mr Afshang was a lovely man with a beautiful thin moustache and eyeglasses. I admired him and accepted what he had said wholeheartedly. After all, he was a close friend of my brother, too.

I had myself participated in demonstrations against the Shah and considered myself a young revolutionary. A revolutionary kid was expected to read revolutionary literature and that was exactly what I was doing on an unforgettable sunny afternoon in May 1980. At breaktime, children were playing in the yard of Khayyam Junior High School, which had newly changed its name to Vali-ye Asr. A first-grade student, I was reading the last pages of the Persian translation of Nous Retournerons Cueillir les Jonquilles (We Will Return to Pick Daffodils) by Jean Laffitte, the French writer. It was a great story about a group of French resistance partisans during the Nazi invasion of France. Mr Nowruzi, the school bookkeeper, came towards me, grabbed the book from my hand and tore it apart in many pieces! I cried and said that I had not finished the book. It was such a lovely story. He smiled a bitter smile it was and left, limping away.

This was a very sad experience. The fact that I was unable to finish the story I loved was terrible but what made it worse was the fact that I didnt understand the reason behind this and Mr Nowruzi didnt give any explanation. However, I consoled myself with the fact that there were other books available to read. My brother and his friends had collected their books and opened a library in our village. They named it Ketbkadeh-ye Shariati (Shariati Library), after Dr Ali Shariati who they considered the martyred Teacher of the Revolution. The library was a room near the gendarmerie on our way to school. It had a black signboard, metal bookshelves, and two folding metal chairs. Sadat and I were the librarians. We were very enthusiastic about our jobs. We felt incredibly special and important. My brother and his friends used to come to the library every afternoon and talk passionately about revolution. After a short while, whispers of worries and concerns were heard about this library. Some older people warned that the library contained communist books which should not be offered to children. The library was closed down and the books moved to our house. Now I had a large quantity of books from which to choose. That summer was one of the best summers in my life. In autumn of the same year, our neighbour informed us that the books had been reported to the Islamic Revolutionary Committee and that one of these nights they would come and search our house. He suggested that we get rid of the books. Late that night, my brother, my father, and I took the books to the basement. A disused water canal had been flowing under our house and there was a dried well in our basement. My father opened the mouth of this well and the two of them threw sacks of books into it while I was holding the lantern. Balzac, Stendhal, Maxim Gorki, Chekhov, Ahmad Mahmoud, Mahmoud Dowlatabadi all went into the well. In an atmosphere of fear and frenzy, I only managed to save one book Mohammad, Prophet to Know Anew (La Vie de Mahomet) by Constantin Virgil Gheorghiu. I told my father that this book was about the Prophet. It is an Islamic book; let me take this. My brother also took a very thick book with tiny fonts entitled Collected Works of Lenin. He said that it was a particularly important book and that we needed to keep it. So we went to the garden attached to the house, dug a deep hole, wrapped the book in plastic, put it in an old leather bag and buried Lenin in our garden under a sour cherry tree.

The above experiences are not unique. Many people in my generation have had similar experiences being denied free access to books. As I grew up, I discovered that there was a censored part to nearly any debate, be it literature, art, politics, history, religion, philosophy, and so on. There was a part that the state didnt want us to see and there was another part that the state magnified before our eyes. There were books that were removed from school libraries and there were books for which we could win prizes if we read them. In my adult life as a poet and writer, I was reminded every day of the restrictions on free expression in various forms. I was asked not to read some particular poems in university poetry readings on numerous occasions. My first collection of poetry was rejected a publication licence and no one cared to explain why. When I finally managed to publish, I was forced to cut out nearly one fourth of each collection. I learnt to use different pseudonyms and adopt various personas to avoid censorship and its consequences. Gradually, censorship became a major preoccupation. I couldnt help but spend much time thinking about it and I found out I was not alone. In almost every gathering of Iranian poets and writers that I have attended during the past two decades, one major topic of discussion has been censorship. People had different perceptions of censorship and different evaluations of its effects. In some cases, immediate consequences of censorship were relatively easy to observe. When a newspaper was banned, I could see that a group of journalists lost their jobs and I lost one source of my information. But to understand how censoring a novel or a poetry collection affects me or anyone else was not that easy. How will censorship affect the corpus of literature produced in the country? Will this effect be lasting? What are the effects of censorship on my creativity? Would I have written differently if I didnt fear censorship? What is the purpose of censorship? Can the government achieve their goals through censorship? Is there any good coming out of censorship? Who supports censorship and why? There were lots of questions and I didnt have a definitive answer to any of them.