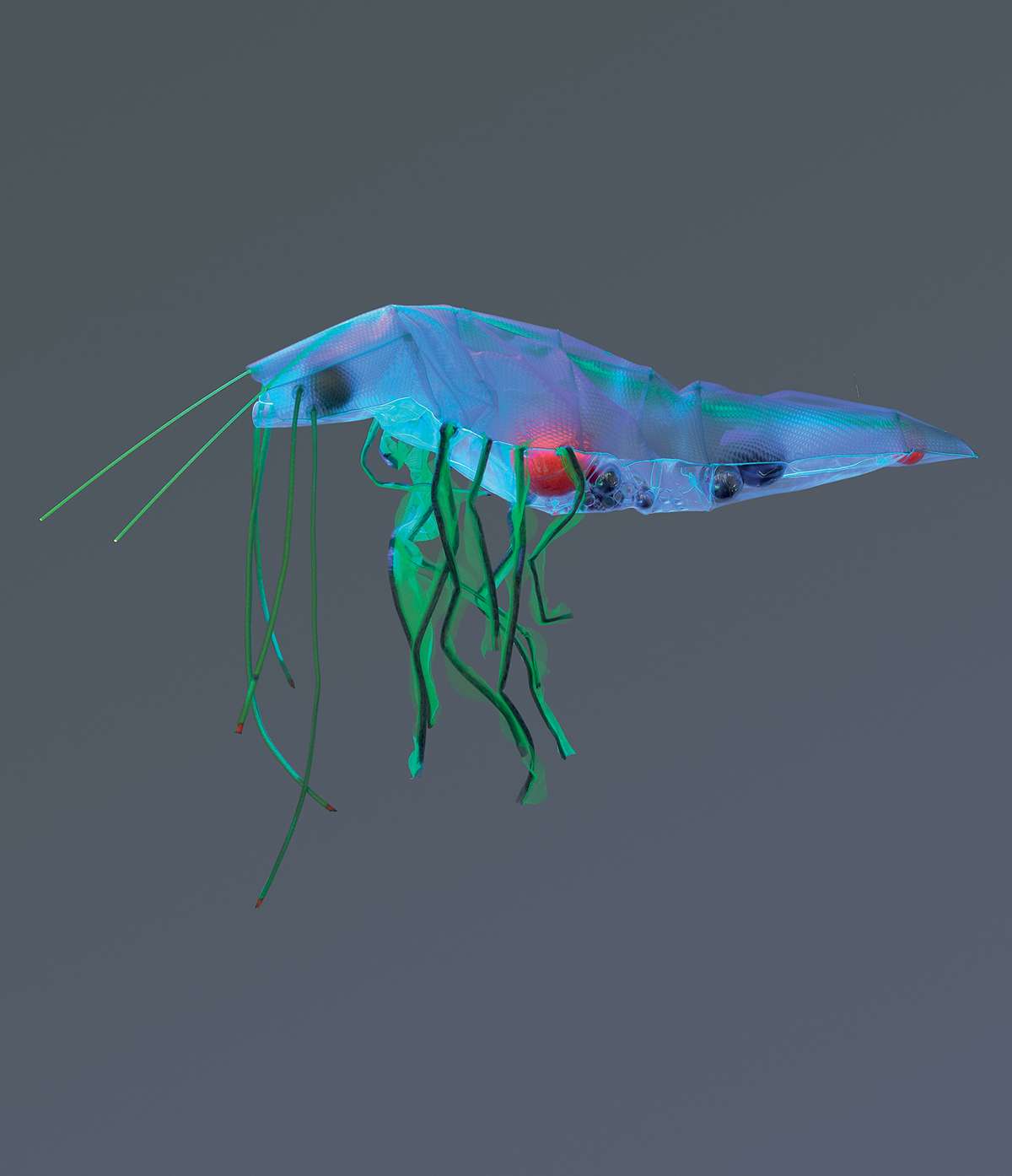

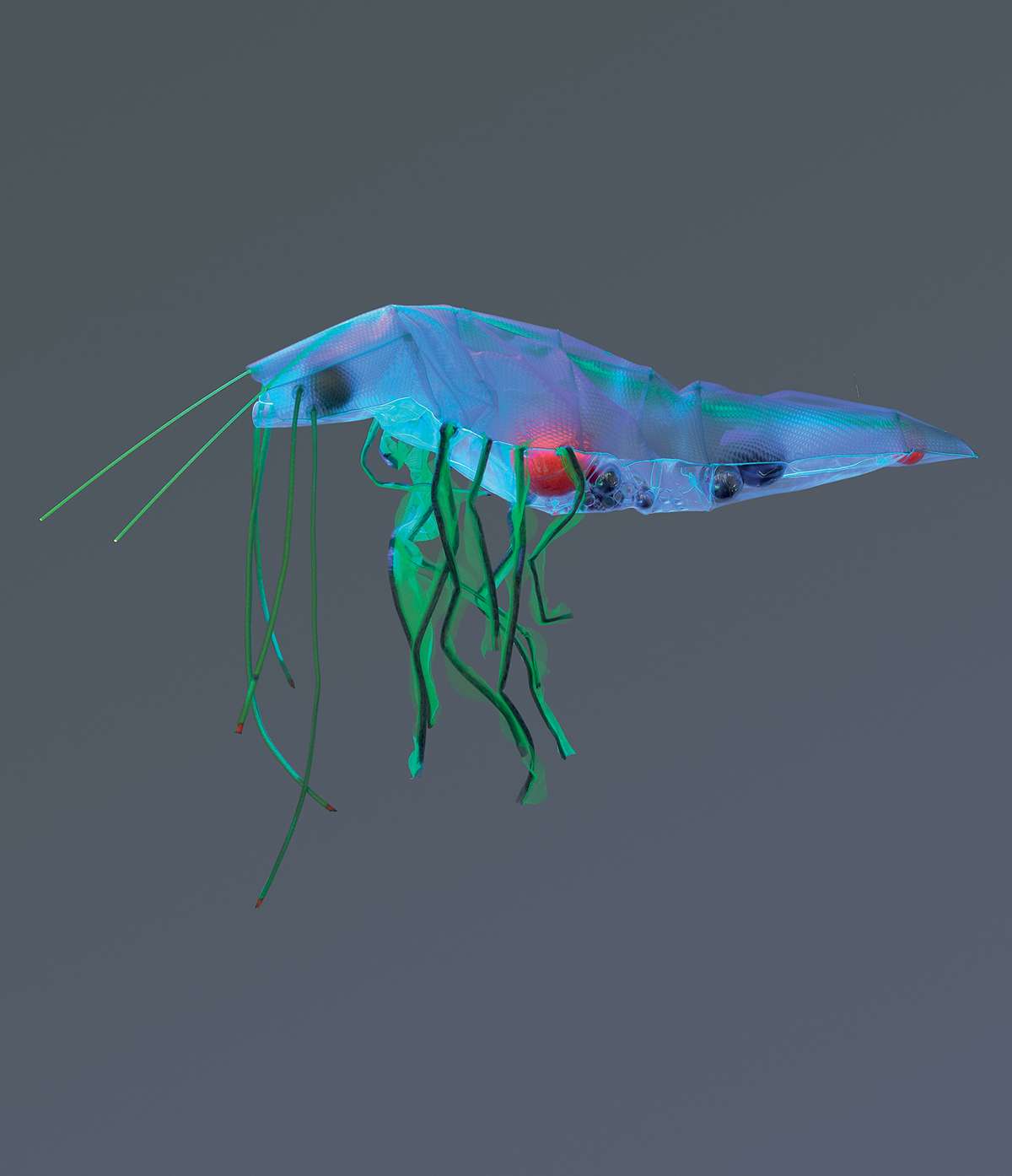

Anne Duk Hee Jordan, Water Crab, 2017ongoing (detail)

About the Authors

Maja and Reuben Fowkes are co-directors of the Postsocialist Art Centre (PACT) at University College London and founders of the Translocal Institute for Contemporary Art. Their publications include Central and Eastern European Art Since 1950 (Thames & Hudson, 2020), the edited book Ilona Nmeth: Eastern Sugar (Sternberg Press, 2021) and Maja Fowkess The Green Bloc: Neo-avant-garde Art and Ecology under Socialism (CEU Press, 2015). Their extensive work on issues of art and climate change includes curatorial projects such as the exhibition Potential Agrarianisms, the Anthropocene Reading Room and the Danube River School, as well as numerous book chapters, journal articles and catalogue texts on topics from digital ecology to the socialist Anthropocene.

Contents

Is my microphone really on? Did you hear me, because Im beginning to wonder? were the words teenage activist Greta Thunberg directed at global leaders in her plea to take seriously climate change and the interlinked emergencies of species extinction, soil erosion, deforestation, air pollution and ocean acidification, and to stop prioritizing economic growth over the future of Earth. Another of the principal voices cutting through the inertia and distractions to confront the enormity of climate disruption and its roots in the current global system based on the pursuit of financial gain has been Pope Francis, who declared that we are not faced with two separate crises, but rather with one complex crisis that is both social and environmental. Amazonian activist Alessandra Korap Munduruku has challenged the Western world to look beyond the climate symbolism of the forest in flames and realize that the Amazon burns with agribusiness, burns to make room for infrastructure projects, with the roots of global warming to be found in more than five centuries of colonial incursions into indigenous lands. These resounding voices articulate the magnitude of climate change, insist that it cannot be considered separately from the multiple signs of ecological breakdown and deepening social injustice, and underline the importance of understanding extractive capitalism and colonialism as its systemic origins.

Even the best-case scenario projected by climatologists, of keeping the global temperature rise within two degrees, will by the end of the century bring the chaos of ever more frequent extreme weather events, uncontrollable wildfires, desertification of land and coastal inundations as permafrost melts and sea levels climb. Correspondingly, climate change has transformed ecology from a single issue into an existential condition touching on and reassembling socio-political, economic and cultural life with implications for all fields of social activity. For theorist Bruno Latour, the climate question is not one aspect of politics among others, but that which defines the political order from beginning to end, forcing us all to redefine the older questions of social justice, as well as those of identity, subsistence and attachment to place. The artistic practices discussed in this account are indicative of the ways in which issues around social justice, land rights, nutrition and wellbeing are today refracted and shaped by ecological concerns. The focus here is on research-based and situated artistic approaches that uncover particular socio-environmental matters in sites of crisis, yet engage in an international conversation that spans geographies and connects with planetary questions. Advocating and animating a new terrestrial politics, social art practices channel gestures of solidarity and care that encompass alternative community building and reach across societal and species divides to contest historical and present injustices. Confronting climate crisis therefore holds out the potential for turning from a perilous course towards ecological restoration, the reworlding of social relations and the resetting of terrestrial wellbeing.

The planetary scale of climate change and the unparalleled threat it poses to the continuity of biological life on Earth has called forth new critical tools and terminologies to comprehend the gravity of the moment. It was concern about rising levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere that first led scientists at the beginning of the millennium to propose renaming the current epoch as the Anthropocene in recognition of the unprecedented impact of humans on Earth systems. Ever since, the realization that human interference in natural processes has taken on geological proportions has captured the critical imagination and informed artistic thinking. Exposing the impact of extractivism, fossil fuels, monocultures, synthetics and nuclear power on Earth systems, artists partake in breaking the spell of the boundless promises of industrial modernity and technological progress to reveal their pernicious role in causing climate disruption. The insight that the roots of climate and ecological crisis lie in the mechanisms of capitalism, understood not just as a global economic system but a way of organising nature, has been defined by Jason W. Moore in terms of the Capitalocene. Further challenges to the West-centric assumption that responsibility for the planet-wide emergency is shared by a generalized Anthropos have emerged from black and indigenous perspectives. Philosopher Achille Mbembe has pointed out that in the wake of the dehumanizing histories of slavery and racism, black experience defeats the very notion of the human species, with the result that there is no longer a human who is not already enmeshed in the non-human, the more than human, the beyond human, or the otherwise-than-human. In emphasizing the notion of the colonial Anthropocene, theorist Macarena Gmez-Barris has foregrounded the underpinning logic of colonialism that continually wreaks havoc on localised social ecologies. Artistic practices discussed in this book have uncovered the toxic dynamics between racial capitalism and climate change, exploring at the same time the coalescence of decolonial reparation and ecological restoration.

Emergent climate epistemologies that arise from critical reassessment of the atomized Western modernist mindset are articulated through art practices that form the building blocks of this account. Such artistic approaches draw equally on the insights of contemporary science and theory, as well as on traditional wisdoms and indigenous knowledges, to overcome the societal disconnect from nature. Among seminal eco-critical influences, theorist Donna Haraway has proposed the term Chthulucene to express the entangled coexistences of critters that writhe and luxuriate in manifold forms and manifold names in all the airs, waters, and places of earth. Molecular biology has similarly revealed that organisms prosper not by competing for resources, but through biotic interdependencies and reciprocal relationships, pointing to what historian of science Isabelle Stengers has called the multiplicity of ways in which life forms compose the world together. An interconnected understanding of the world that does not divide the human realm from the multitude of living beings and natural entities flows through many indigenous and traditional worldviews. As anthropologist Marisol de la Cadena has related, resistance to extractivism on indigenous lands is not just a matter of environmental conservation, but also a cosmopolitical struggle to recognize mountains as not only geology but also earth-beings. In light of these insights, climate change is approached here as a planetary process that affects not only populations across the globe but also natural entities, interferes in vegetal worlds, conditions animal existences and demands a radical rethinking of the human in the terrestrial order.

Next page