Imperialism and Hellenic Civilization

In the Foreword to The Formation of the Greek People I set forth the plan of our Greek series. Two of the volumes devoted to Hellenism, I said, give an outline of the great historical framework. They analyse the various contingencies, of place, race, and individuals, and bring out the circumstances of every kind which contributed to the organization of the Greek pities, created Hellenic civilization, and then caused it to radiate far and wide. We have, as far as it is possible, explained the Greek miracle, the splendid efflorescence of an individualism which had been seen nowhere else. We have defined the characteristics of the Greek spirit in religion, art, and speculation, and the original constitution of the City. Now, therefore, in this last volume, have to study the new conditions which favoured the expansion of Hellenism, while causing it to be profoundly transformed. Here M. Pierre Jouguet deals with the problem raised by M. Jarde in The Formation of the Greek People : How in that fundamentally individualistic Greece, where small collective individualities were as intensely living and tenacious of independence as individual men, did political unity, born late and imposed from outside, affect the civilization which was expressed by the common language, the Kotvr], and had hitherto been the one bond uniting the Greeks?

With the victory of Macedonia, of the territorial state more or less Hellenized but originally alien to Hellenism, over the City State, the polis, whose expansion consisted in the creation of other cities, a new epoch of history begins, a new world rises. The essential factor of this development is imperialism.

We have seen that the history of mankind, being based on the identity of its elements, tends to the organization of men in groups and the fusion of groups with one another. Human affinities, racial affinities, interest, of course instinctive altruism and reasoning altruism here play their unifying part, But we have also noted that egoism, that of groups and that of individuals, the will to power and betterment, also creates unity in its own way by domination and subjection; that is, properly speaking, imperialism.

Sometimes, too, imperialism is tempered, is tinged with motives and sentiments which render it less oppressive, and fit to become a factor for deep-seated unity. Such was the case with the imperialism of Macedonia.

I have already observed that Macedonia whose army was the heart of the nation, whose King was the leader and comrade of his soldiersplayed a part in Greece similar to that which the military state of Prussia was to play in Germany. But the will to power, which in Philip had given the hegemony to Macedonia, was not merely strengthened in Alexander; it was actually enriched, and ennobled by various elements.

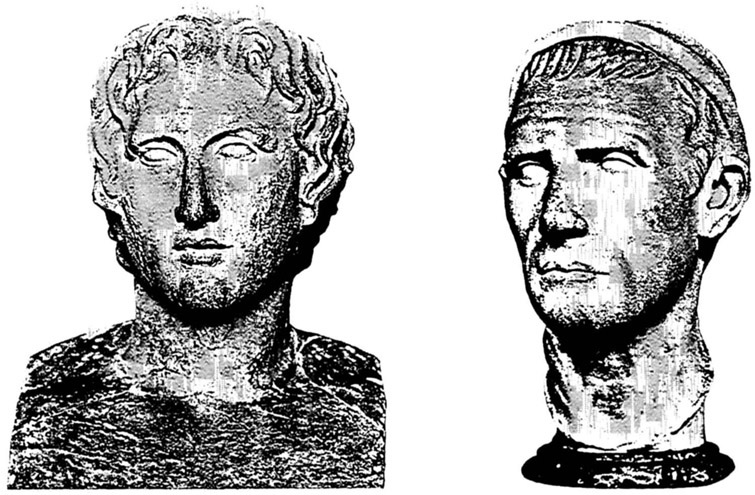

In this volume M. Jouguet has well brought out the complex nature, the charming and sometimes disconcerting character of Alexander, the hero of that prodigious epic, who was so prematurely buried in the purple of his victories.

What first strikes one in Alexander is the inner energy which makes man truly a man and of his faith in reason. He placed his genius and the military power which he had inherited at the service of a certain idea of Hellenism which was in the moral air of his day, took more definite shape in him, and was amplified by the very course of his victories.

To be a Greek, in those days, was, first of all, to be contrasted, as a free citizen, with the Barbarian subject of a despot; it was to cherish the pride of Salamis; it was to aspire to a fuller vengeance on the erstwhile invader. In addition, the dazzling wealth of the East and the precedents of myth and legend Dionysos, Heracles, Achilles, the Argonautsadded their suggestion to those of national pride. But to be a Greek was also to be contrasted with the citizen of the narrow polis as a man who was fully a man just because he was a Greek, and whose worth lay in his culture. What made the Greek, Isocrates proclaimed in his Panegyric, was education, not origin; so every cultivated man, ,vos, was a Hellene.

Panhellenism thus conceived ended in cosmopolitanism. Amid the everlasting wars of cities and conflicts of parties which were exhausting Hellas more and more, the Wise Man came to look for law in his conscience, for true liberty in moral liberty, and for his true fatherland wherever wisdom reigns. Moreover, the exiles, cityless men (), the condottieri of antiquity, ready to go all over the world, alone or in bands, for love of adventure or greed for gain, put these cosmopolitan tendenciesless nobly, it is true into practice.