To the onlie begetter, M. (again)

Contents

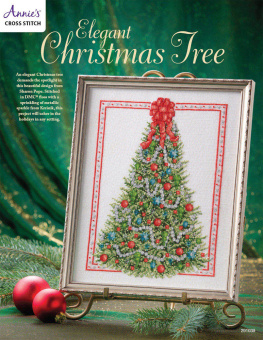

E VERY YEAR, IN THE MIDDLE of London, a huge Norway spruce, twenty metres and more in height, is erected in Trafalgar Square. Many who see it must take it for granted. It is Christmas time, so lets put up a tree. You see the trees everywhere, all over the world, even in countries which are not avowedly Christian. After all, a tree is wonderfully neutral, no? Unlike a manger and a crib, where the infant Jesus lies in the straw watched over by the Virgin and worshipped by angels, it conveys no potentially divisive religious message. A tree is a tree, and in so far as it brings people a message, it is surely a comforting, pagan sort of message, suggesting the abiding, evergreen life of Nature, even during the iciest, darkest months of the year. So, our hearts warm to the sight of a Christmas tree with its lights, whether we are seeing such an emblem in Berlin or New York, in Melbourne or in Stockholm, in Tokyo or Harare.

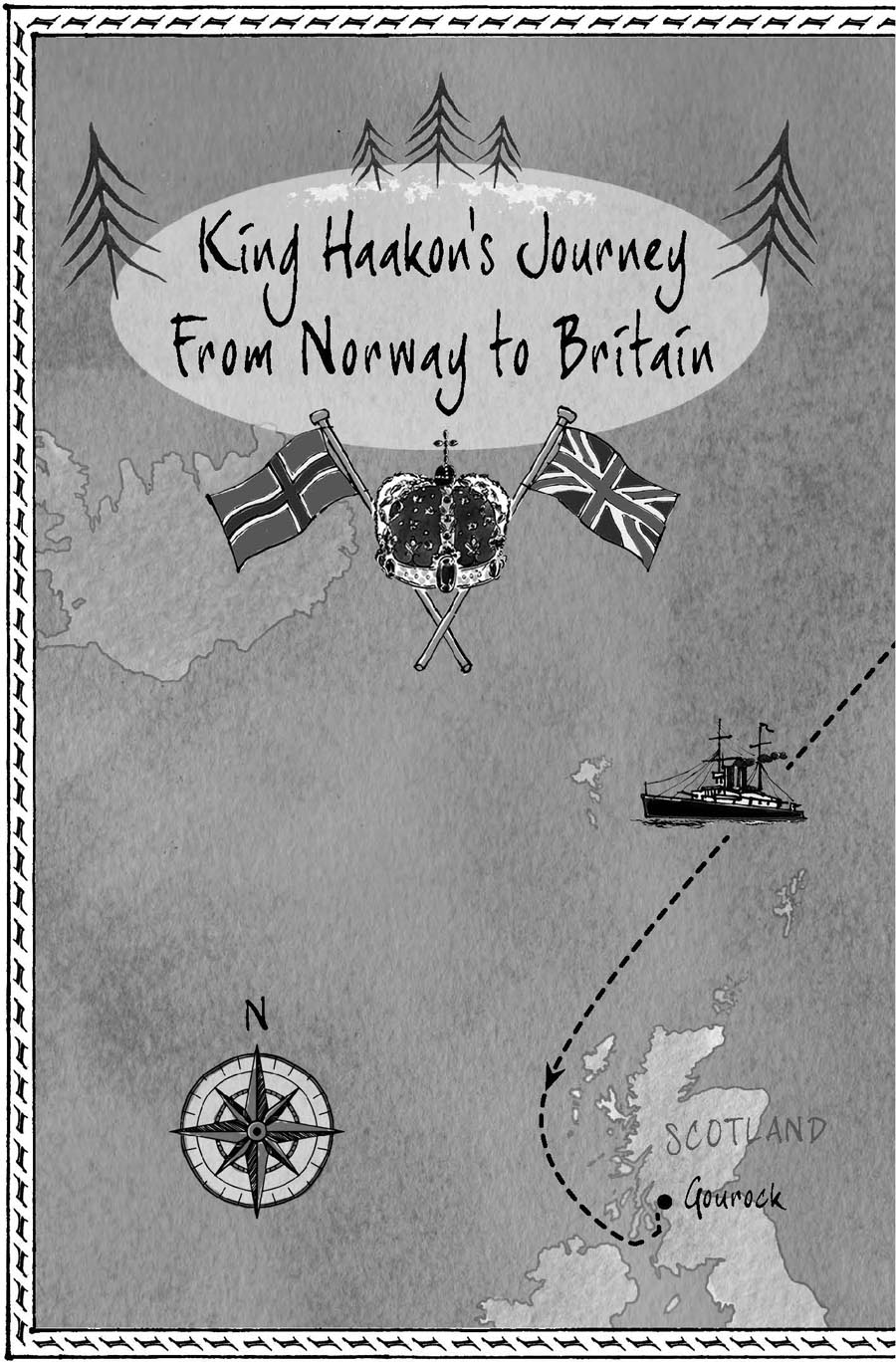

The London tree, however, tells us a particular story. It is the story, really, of a king, a very remarkable king, and of his people, the brave, indomitable people of Norway. The Christmas tree in Trafalgar Square is not just any old tree, such as you might see decorating a shopping mall or a civic space, any old where.

At the base of the tree stands a plaque, bearing the words:

This tree is given by the city of Oslo as a token of Norwegian gratitude to the people of London for their assistance during the years 194045.

A tree has been given annually since 1942.

Though it comes and goes each year, and is to that extent as ephemeral as the seasons, the Norwegian Christmas tree could claim to be among the most remarkable memorials contained in that square, which is so packed with links to history.

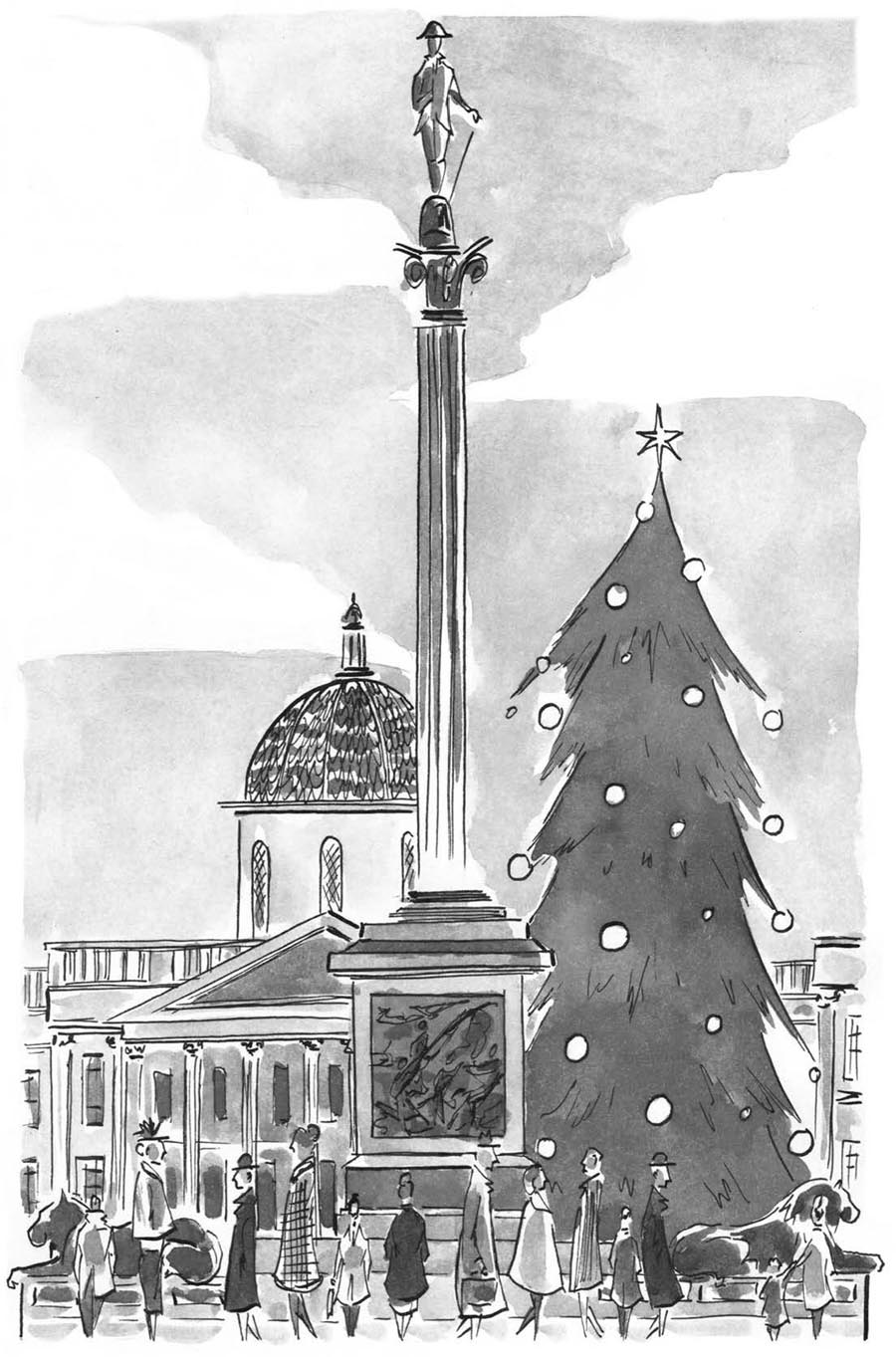

Trafalgar Square is a spot to which most visitors to London will gravitate at the heart of this capital city, and they will see that it is filled with monuments denoting our countrys past. Standing at its northern side, on the steps of the National Gallery, you look down towards Nelsons Column, beyond, the wide thoroughfare of Whitehall, leading towards the Houses of Parliament. Your eye will take in many reminders of British history; you will see King Charles I, sitting on his horse and gazing down to Banqueting House where, on a cold January day in 1649, on a hastily erected scaffold, he was beheaded; in the centre you will see the gigantic Nelsons Column, erected to commemorate the brilliant naval hero who, in 1805, defeated the French Navy at Trafalgar (hence the name of the square) and ultimately prevented the all-out conquest of Europe by Napoleon. At the Battle of Trafalgar, Nelson was picked off by a French sniper and died, leaving a navy, and a nation, both grief-stricken and proud.

Trafalgar Square is a spot to which most visitors to London will gravitate at the heart of this capital city.

As your eye moves across the square, you will also see, in statues and busts, figures who are perhaps less familiar, such as Havelock and Napier, heroes in their day, as soldiers who solidified the British hold on India and fortified the creation of the Raj.

History is not a neutral story. The monuments erected to commemorate the men and women of previous centuries are often uncomfortable reminders that, in the past, people had different perspectives, different scales of value altogether. When they erected the statue of Charles I, it was to show what they thought about him but also what they thought of those who had beheaded him. And that debate between those who think monarchy is a good system and those who would prefer Britain to be a republic never entirely went away.

The Victorians who erected statues to Napier and Havelock felt absolute confidence that the British brought benefits to India, with the East India Company and, subsequently, the Raj. In todays world, that breezy imperialism is, to put it mildly, frowned upon. No one who reads of Havelocks or Napiers wars against the people of India can view their statues without feeling a little queasy.

Even the great Lord Nelson, on top of his column, halfway to heaven, is not so heroic to everyones scale of value. Superb naval commander he may have been. Clever, charming lover of Lady Hamilton. But tainted now, as historians would wish to remind us, by having defended Jamaica against French incursions. I have ever been and shall die a firm friend to our present colonial system, he wrote at the time, apparently condoning the use of enslaved people in the sugar plantations. The past is a foreign country, as a famous novelist once began his best novel by saying. It is, we can readily admit, not merely another country, it is a bloody, cruel country.

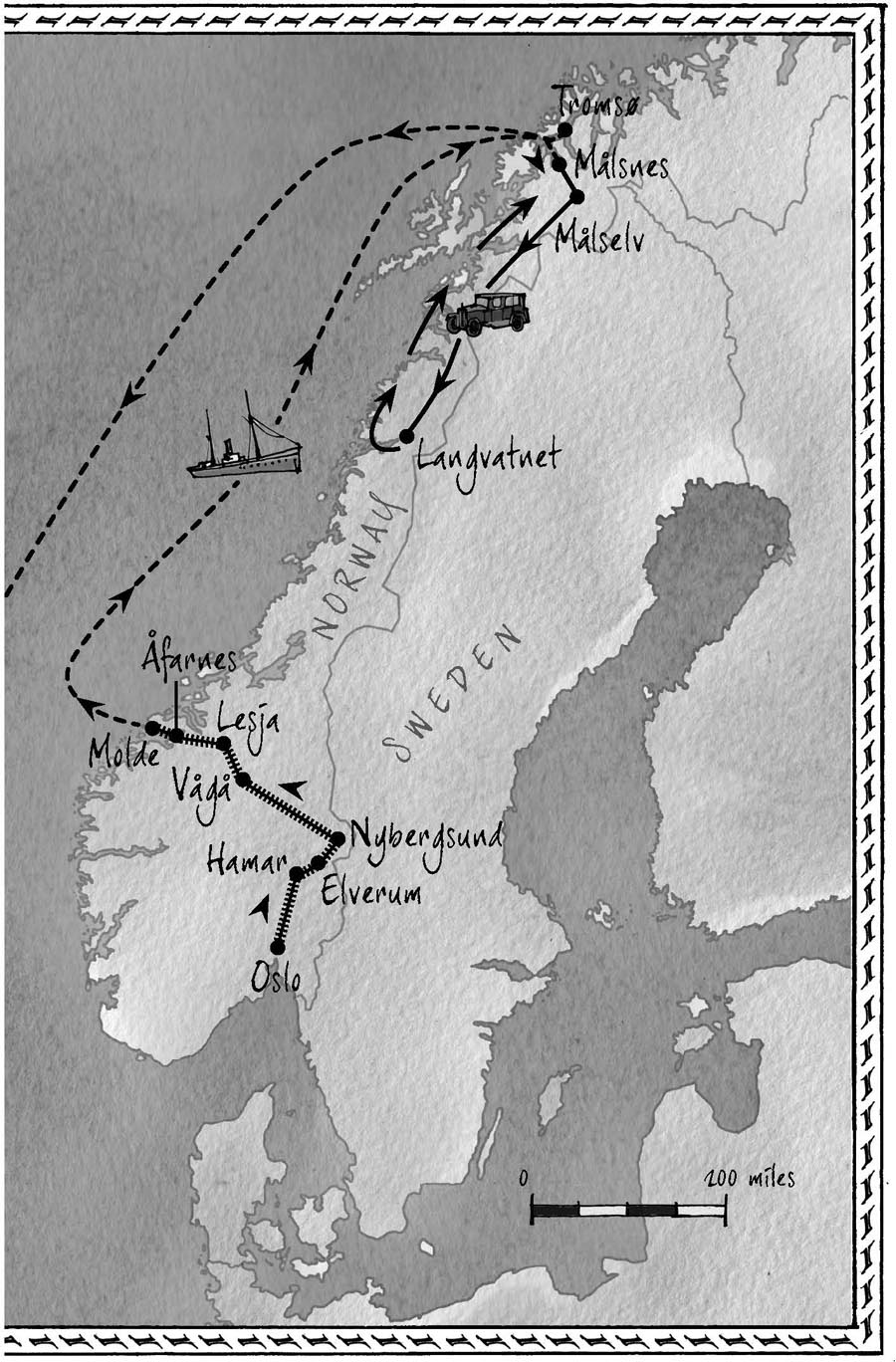

One of the cruel leisure activities of Londoners in the past was to visit the Bethlem Hospital Bedlam and to mock the mentally afflicted patients, prodding through the bars and laughing at their apparent absurdity. Present-day visitors to the past sometimes seem like that, so confident of their own superiority to the benighted people who fought wars, built empires and believed in outworn creeds. Occasionally, however, when we return to that foreign country, the Past, we are confronted with a story which stirs uncomplicated admiration, which flutters our hearts, which makes us feel that, wicked and muddled and misguided as the human race has so often been, just occasionally there has arisen a person of courage, integrity, decency, at a period in history when these qualities were under threat. By his refusal to surrender those values to an unspeakable evil, by his love of his country, of which he was the King in exile, King Haakon VII of Norway was such a man.

***

Every year on 30 January, royalists come to lay wreaths at the statue of King Charles I at the bottom of Trafalgar Square. But for every royalist who does so, there is probably a republican who thinks, had they been alive in the seventeenth century, they would have fought in the Civil Wars for what was called the Good Old Cause. And there must also be many modern democrats who think, whether or not they support a monarchy, they would not want the sort of absolutist monarchy which Charles tried to impose by force, taking up arms against his own people.

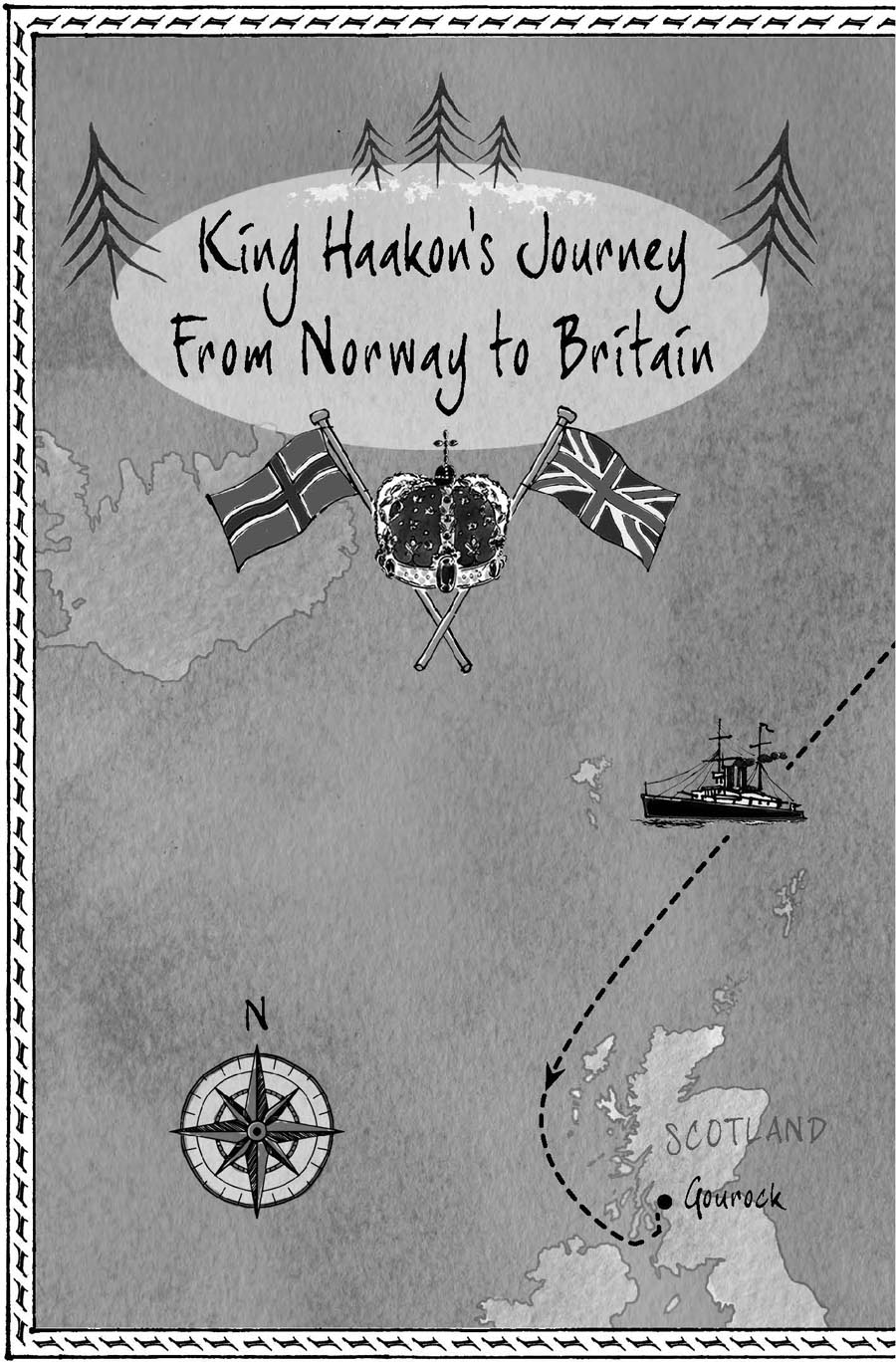

A month before the royalists gather to commemorate the Royal Martyr (as they see him), the Norwegian Christmas tree tells another story, this time of a very different king, and of a very different time. It is a story which, of all stories in modern times, is the most likely to make even the most secular-minded, republican democrat see the point of monarchy. Even for those who might consider this sentimental, the tree reminds us of the political and social values that were being defended, with such amazing valour and determination, when the first tree was erected in 1942. That tree, and every tree since, has spoken of what the friendship stood for, between Norway invaded but refusing to accept conquest and Britain resisting, not the German-speaking people, who probably invented the idea of Christmas trees, but the dark powers of the Third Reich. The hundreds of white lights that decorate the tree are beacons of an imperishable light, memorials of a remarkable story. The story reminds us how much difference can be made to history by just one individual possessing the rare gift of moral courage.

Next page