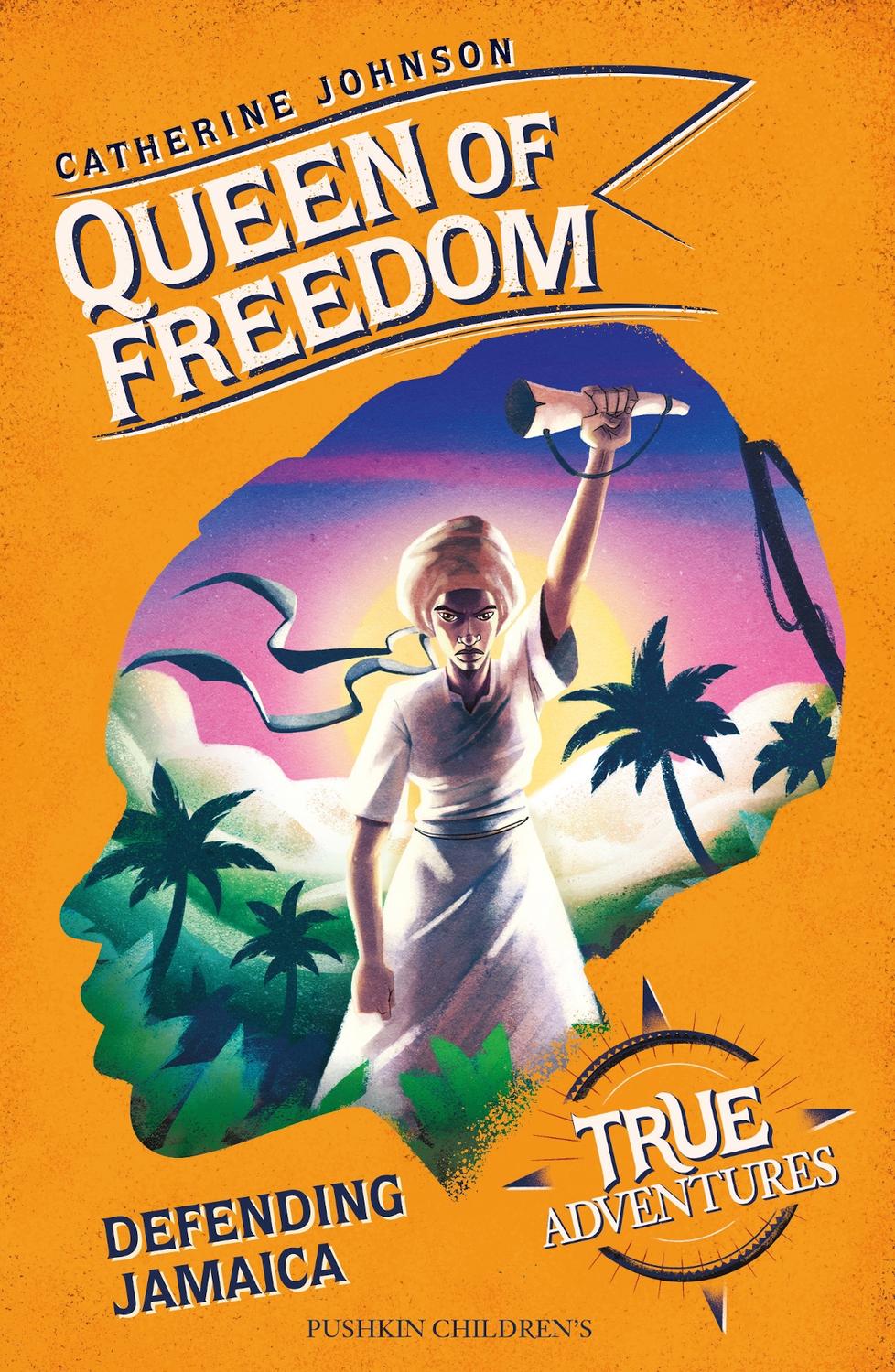

In the Blue Mountains, Parish of St George

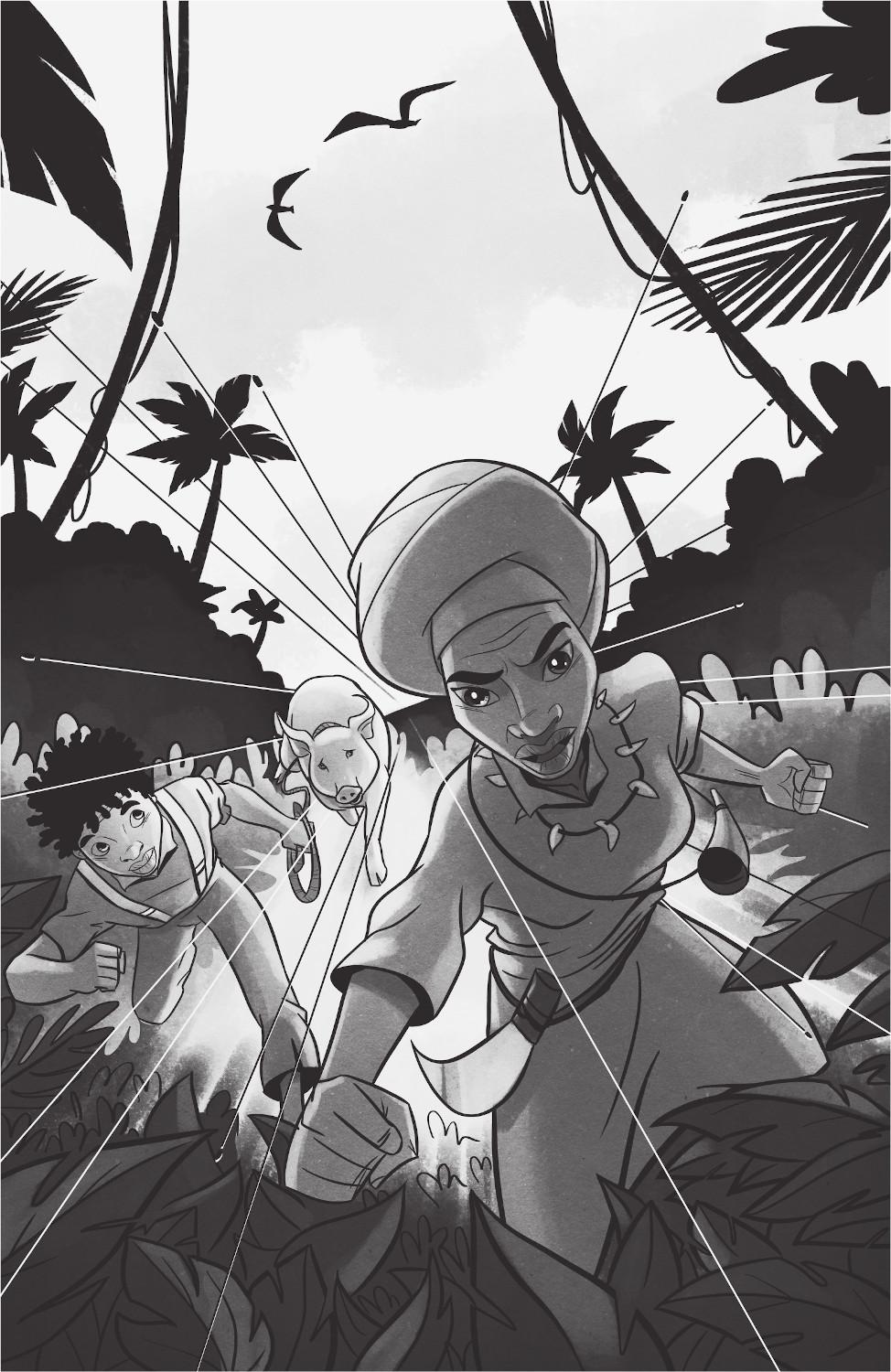

T he raid had been a mistake. The redcoats were after them, crashing through the trees and undergrowth.

The cows Quao and Johnny Rain Bird had stolen would be useful, but not if they all ended up dead. Nanny told the men to go east and circle back to town; she and Yaw and the pig Michele would go west.

But she had been running for so long and the redcoats were still coming. The thorns cut her feet, tore at the skin on her legs, and vines whipped her onwards. Behind her the soldiers snapped branches, shouted threats. Birds flew up, calling, yelling. As she ran, the cutlass as long as her thigh slapped and bounced against her leg.

The boy and the pig galloped ahead.

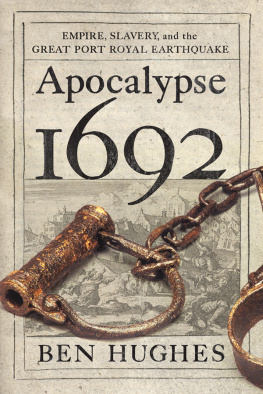

She had been hunted before. So had Yaw. The times she thought she had escaped, only to be dragged back, punished with shackles and chains and beatings. She would not let them catch her now. She would never go back to the cane fields, to the lash and the overseer and the buckra. Never. And she had responsibilities now, to the village, to her new family. She should never have agreed to taking the pig with Yaw. Had she ever been a child? She could not remember.

Yaw looked back at her, grinning. This was all still a game to him. Her heart was beating so hard and so fast she thought it might leap out of her chest.

Run, Yaw! she called.

Then a sharp crack-crack. She thought it was a branch, at first, breaking. Then another, a hard, dry snapping noise. Then another sound, a whirring a bird, a hornet? No, something else cut the air past her face.

Bullets. They were shooting at them.

Another whistled past. Her skin stung: it had grazed her, made a red line across her upper arm.

They would kill them both. She heard them reload. Up in the trees a monkey screamed.

Yaw! she yelled. Faster!

Stop! In the name of the King! The soldiers voice bounced off the leaves and the hills.

She had caught up with the boy now. The pig, head down, was almost pulling him along.

They cannot catch us, Nanny, Yaw said. The gods are on our side! We stole Michele and we will take her home. We will

Another crack-crack-crack and Yaw pulled up, stock-still. Then, as the world stopped, he crumpled to the ground and Nanny watched open-mouthed as he folded in on himself in the way the shamey plant leaves curl up when you step on them. A red flower bloomed above his temple and his eyes turned up inside his head.

Nanny reached him as he let go of both the rope and the pig, his hand loose, his fingers useless. Michele stopped too; she snorted, her white flanks heaving. Nanny halted, bent over Yaws body as another volley of bullets cut through the air right where her head had just been.

Yaw! Nanny cried out. She felt his pain like a blow to her chest.

She looked up and could see the flashes of red and gold where the soldiers moved between the trees. She knew she was next.

She gathered him up in her arms. The charms he wore on a string in a tiny cloth bag around his neck hung loose. His head was all meat now. The soldiers were closer.

Nanny blinked; her hands were wet with sweat and Yaws blood. She had to put him down but she whispered into his one whole ear, I will not leave you, Yaw.

Then before the redcoats came any closer, she wiped her palms on her plaid cotton dress and shinned up a soursop tree. Clinging and flattening herself on a branch directly above the body of Yaw lying on the forest floor, one eye ruined, one staring up at the blue sky she shut her eyes and tried to imagine his spirit floating past and flying home across the wide ocean.

Michele, the pig, stayed close, nudging Yaw as if he might get up if only he had some encouragement.

Then suddenly the soldiers were upon him. Four men burst upon the track like monsters, pink and red-and-white and gold, their whiskers bristling, their weapons dark. They smelled of gunpowder and sweat and death.

One kicked the boy as if he were nothing. Michele squealed and went for the red-faced soldier before running off into the bush. Another cursed and aimed for the pig with his gun, but Nanny was pleased to note Michele was too fast.

The tallest soldier bent over Yaw and pulled his shirt down off his shoulder.

Hes one of the Fairview slaves, he said. From over Mount Vernon. Theres the mark there, Captain Shettlewood.

Yaws shoulder bore a lumpy raised scar. Nanny blinked. She remembered the pain when the hot iron had seared those same letters and the shape of a heart onto her own skin.

Good shooting, Geoffrey, the redcoat called Shettlewood noted. Only a few more to round up, although Mr Noach would rather have all the property returned alive.

Yes, sir. The soldier tried to click to attention. Pigs alive, though.

Lost in the bush? The captain poked at Yaw with his foot. That animals as good as dead.

What should we do with him? The boy? The soldier wiped the sweat off his face.

Leave him, the captain said, bending over Yaws body. The ants will soon eat out his eyes. A warning to the others. Well find her soon enough too.

The soldiers looked around the clearing as if willing her to appear. Nanny put her hand on the hilt of her cutlass. But there were too many of them

When the reinforcements arrive, Private Geoffrey the captain said, standing up we will wipe those Maroons from the face of the earth. We know their village cant be more than a few miles from here. Its only a matter of time.

Yes, sir!

Nanny wished she had a gun. She wished she could rain down all the worst things on those mens heads. She prayed to bring down the shit of every bird, the vomit of all the monkeys. She stared. She sent all the hatred that flooded through her body down onto those soldiers.

As the men walked away, Nanny saw one of them slip, heard him curse with pain as his knee turned over. Perhaps it was Obeah, the old magic? Perhaps the gods had not forgotten them after all.

She felt the anger rise inside: if they were here, then why was Yaw dead?

When she was sure they had gone she carefully inched down the soursop tree, almost holding her breath just in case the soldiers were still there. Then she heaved the small boys body across her shoulders and disappeared into the bush along the faint whisper of a track the soldiers had not seen.

It was hard going, running and hiding through the bush with Yaws body on her back. When she reached their makeshift village, Nanny laid the little boy down outside his hut. She took the old cow horn trumpet, the abeng that hung from the hog-apple tree and blew as hard and as long as she could.

First Efua and Helen came out from the gardens where they were tending sorrel and callaloo, then Johnny Rain Bird and Quao came from the forest where they were cutting wood to make a pen for the cows. Soon the whole town was there. There were some tears when they saw Yaw lying still and dead, but most of her fellow Coromantees had seen suffering of one kind or another.