State of Black Librarianship

Take advantage of every opportunity; where there is none, make it for yourself.

Marcus Garvey

Five decades after E. J. Josey first chronicled the state of Black librarianship and almost a decade since the last narrative of African American librarians was documented in the 21st Century African American Librarian in America, we are taking the temperature of Black librarianship as we begin the third decade of the twenty-first century. In short, the state of Black librarianship is tied to the state of the Black community.

During the past year, Americans experienced a global health crisis that took the lives of hundreds of thousands of Americans and millions worldwide, with Black Americans twice as likely to contract the novel COVID-19 virus and twice as likely to die. The health crisis led to the worst economic downturn since the 1930s, and again Blacks were disproportionately affected. Add to this unkindly mix racial justice protests triggered by the unarmed killings of Black and Brown people at the hands of the police. Combine that with the fallout from a contested presidential election fueled by a disinformation campaign that led to a full-out insurrection at the US Capitol and efforts to roll back access to the ballot particularly targeting the voting rights of Black Americans under the guise of fighting false accusations of massive voter fraud. If it were winter in America, then it would be a blizzard in the Black community.

As institutions, libraries can be equalizers helping us understand our past and our current condition or institutions of inequality providing a one-sided view of information and knowledge. The fact is that ten years after publishing The 21st-Century Black Librarian in America: Issues and Challenges, Black librarians are still fighting implicit bias with the right to not only have a seat at the table but to lead. Black librarians still have to work twice as hard and have the best education and rsum to be considered for an entry-level position. We often get much less pay and acknowledgment for our work and are judged by a separate and unequal set of standards. We endure microaggressions or blatant discrimination and racism and are often told that our complaint or allegation does not meet the standard for discrimination.

Yet there are those who point to significant progress for Black people in LIS leadership positions. Today, the Librarian of Congress is a Black woman. We currently have back-to-back African American presidents of ALA and an African American executive director of ALA.

The Black activists who founded the Black Caucus would be very proud of the response and activism of BCALA leadership and members over the past year. The Black Caucus has and should continue to be the training ground for leaders in the profession and in ALA. With active BCALA members elected to lead ALA and many more members elected to ALA division leadership and the ALA governing body and appointed to lead ALA committees, we are sitting at the table and making a difference. In fact, 2020 saw three Black ALA division presidents, from AASL, ALSC, and ACRL, three of whom previously served on the BCALA Executive Board.

Even with a Black woman Librarian of Congress, the racial climate at our nations library rivals that of fifty years ago.

As Black librarians, we must remain active in our communities and libraries, being civically engaged and advocating for policies that lead to inclusion. In the words of W. E. B. Du Bois Now is the accepted time, not tomorrow, not some more convenient season. It is today that our best work can be done and not some future day or future year. But we cannot act in isolation. Coalition building is the way forward for advancing an inclusive ALA and advocating for services in our communities. BCALA must be a leading voice for librarians of color working with the National Librarians of Color (NALCO).

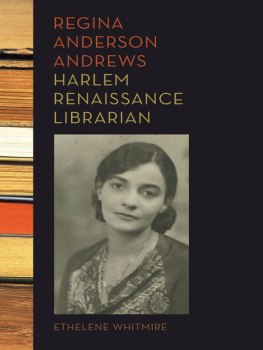

Moving forward, Black librarians must connect with and find strength in our Black librarian lineage heeding the wisdom of those who have gone before us. Ancestors like Clara Stanton Jones, E. J. Josey, Alma Jacobs, Joseph Henry Reason, A. P. Marshall, and so many others provided the blueprint to organize and advocate for Black librarians and library service to Black communities. Fredrick Douglass reminds us that the efforts and struggles of our ancestors may be a moral one, or it may be a physical one, and it may be both moral and physical, but it must be a struggle. Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.

Our trailblazers paved the way for those who follow, and we must continue to demand better treatment. We must center ourselves in the narrative of Americas past, present, and future and reject the current narrative that does not center us. I know it is and has always been exhausting to be a Black librarian and work in spaces that do not want to include us; however, we must continue to fight for a brighter future for Black librarianship and library service to Black people. After all, this is the debt we owe our ancestors and the price we pay for our space on earth.

Notes

. Amy Jacques Garvey, Garvey and Garveyism (Garvey Press, 1963).

. See Ringer v. Mumford, 355 F. Supp. 749 (D.D.C. 1973); Cook v. Billington, C.A. No. 82-0400.

. Press Release: BCALA Statement to ALA Council against Racism. Black Caucus of the American Library Association, March 17, 2021.

. W.E.B. Du Bois, Frederick Douglass, and Booker T. Washington. Three African-American Classics: Up from Slavery, The Souls of Black Folk and Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass. (Courier Corporation, 2012.)

. Ibid.

Bibliography

Black Caucus of the American Library Association. Press Release: BCALA Statement to ALA Council against Racism. March 17, 2021.

Du Bois, W. E. B., Frederick Douglass, and Booker T. Washington. Three African-American Classics: Up from Slavery, The Souls of Black Folk and Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass. (Courier Corporation, 2012.)

Garvey, Amy Jacques. Garvey and Garveyism. Garvey Press, 1963.

About the Editors

Shauntee Burns-Simpson (MLIS) currently serves as the 20202022 president of BCALA. She is the associate director of school outreach for the New York Public Library. An ambassador for libraries and youth librarians, President Burns-Simpson enjoys connecting people to the public library and its resources. She works closely with at-risk teens and fosters a love of reading and learning with her innovative programs. In addition to leading BCALA, she chairs the American Library Association Office of Diversity, Literacy, and Outreach Services (ODLOS) Committee on Diversity.

Nichelle M. Hayes (MPA, MLS) is the BCALA president elect and current vice president. She leads the Center for Black Literature and Culture (CBLC) at the Indianapolis Public Library. Hayes graduated from Indiana Universitys School of Library and Information Science (SLIS) and began her library career as a library media specialist at an elementary school in Indianapolis. Later, she worked as an adult reference librarian specializing in business. She serves on a number of organizational boards throughout the state of Indiana, including the Indiana Black Librarians Network (IBLN) as immediate past president and the NAACP Greater Indianapolis Branch. She is also a member of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority Inc., a public service organization. Vice President Hayes blogs at https://thetiesthatbind.blog/, where she discusses genealogy and keeping families connected.