Copyright

Copyright Val Shushkewich, 2012

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise (except for brief passages for purposes of review) without the prior permission of Dundurn Press. Permission to photocopy should be requested from Access Copyright.

Editor: Jennifer McKnight

Design: Jennifer Scott

Epub Design: Carmen Giraudy

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Shushkewich, Val, 1950

More than birds [electronic resource] : adventurous lives of North American naturalists / Val Shushkewich.

Includes bibliographical references.

Electronic monograph.

Issued also in print format.

ISBN 978-1-4597-0560-9

1. Naturalists--North America--Biography. 2. Natural history--North America--History. I. Title.

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council for our publishing program. We also acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund and Livres Canada Books, and the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Book Publishing Tax Credit and the Ontario Media Development Corporation.

Care has been taken to trace the ownership of copyright material used in this book. The author and the publisher welcome any information enabling them to rectify any references or credits in subsequent editions.

J. Kirk Howard, President

Visit us at: Dundurn.com

Definingcanada.ca

@dundurnpress

Facebook.com/dundurnpress

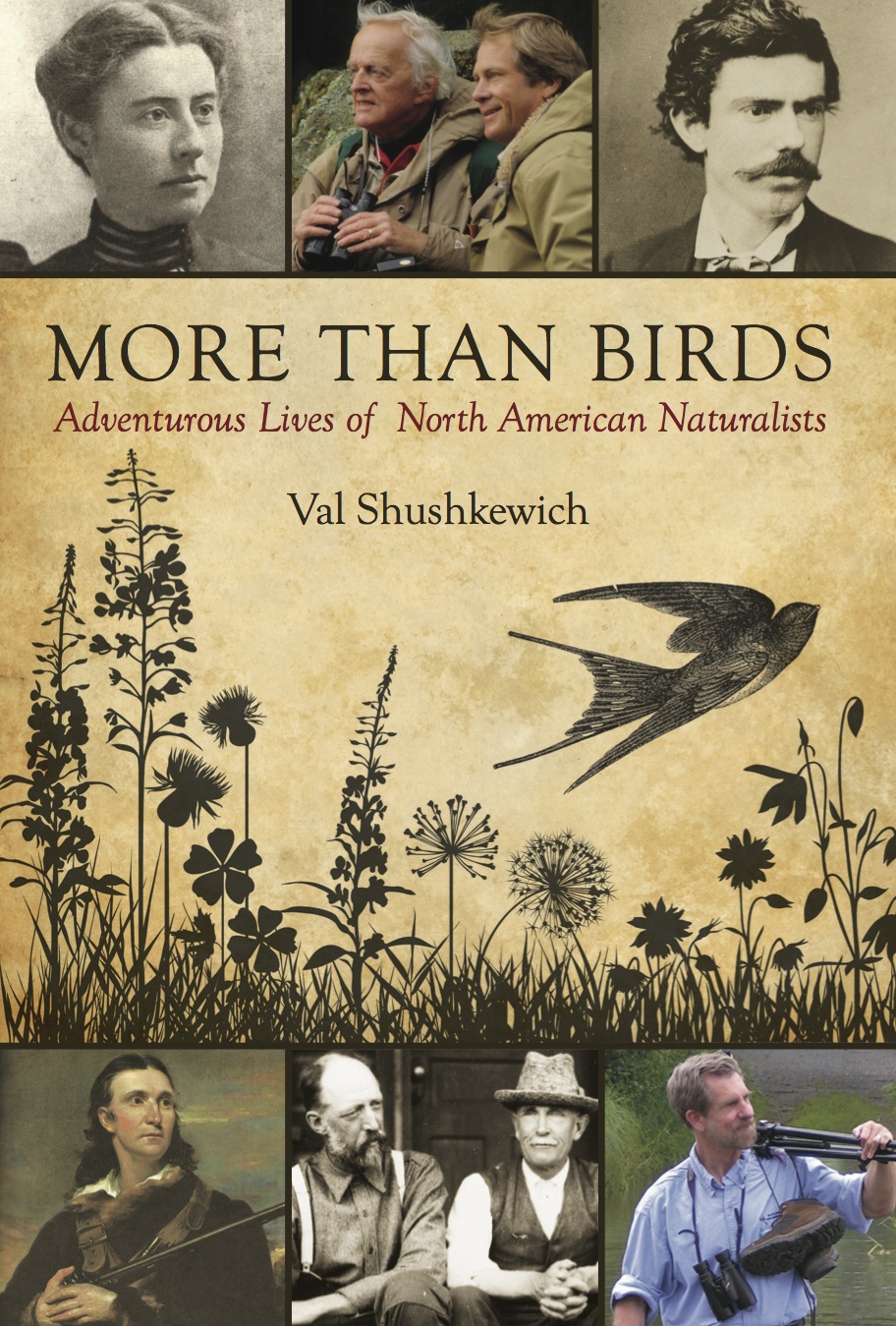

Cover images:

Top left: Cordelia Stanwood, courtesy of the Stanwood Homestead Museum and Stanwood Wildlife Sanctuary.

Top middle: Roger Tory Peterson (L) and Robert Bateman, courtesy of Birgit Freybe Bateman.

Top right: Robert Ridgway, courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Archives, image #SIA2008-4347.

Middle images: Composite image by Jennifer Scott

Background: Perter Zelei/iStockphoto

Bird: ilbusca/iStockphoto

Plants: Olga Axyutina/iStockphoto

Bottom left: John James Audubon, painting by John Syme, 1826.

Bottom middle: Percy Taverner (L) and Allan Brooks, courtesy of the Canadian Museum of Nature, Neg. No. 56275.

Bottom right: Kenn Kaufman, courtesy of Kimberly Kaufman.

Dedication

To the memory of my parents,

George and Irene Cuffe,

who gave me a love of nature.

Contents

Acknowledgements

T he author would especially like to thank Barry Penhale of Dundurn Press (formerly with Natural Heritage) for encouraging her with this book and a previous book, The Real Winnie: A One-of-a-Kind Bear. She is extremely appreciative of his believing in her writing, and for the valuable advice he has given her, as well as for his overall guidance. A special thanks is also given to Jane Gibson for her editorial support on both books.

The author would also like to acknowledge the interest and friendship of Claudia Angle of the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History, and to thank her for sharing information about the North American bird specimens and exhibits.

Introduction

T he twenty-two naturalists in this book exhibit selflessness in their pursuit of knowledge. They are driven by an inner passion, and are not motivated by money or fame. They love their work and persist in it, often enduring hardships and sometimes the skepticism and criticism of others who cannot appreciate what they are accomplishing.

This book shows some of the connections between one generation of naturalists and the next. In reading about the life of one of these individuals, the names of some of the others very often appear. These people are eager to share their knowledge and often go out of their way to make contact with each other. In some cases an aging naturalist and one just starting out become good friends. They do not resent the accomplishments of others, perhaps because they are so self-confident in their own abilities and achievements. The greatest men and women in science are often also the most modest; perhaps because they have found that the more you discover about the natural world, the more you realize how little you really know about it.

More Than Birds: Adventurous Lives of North American Naturalists shows a progression and course of development in nature studies, with later advances building upon earlier work. It shows how bird studies have evolved and changed direction over time. The book does not attempt to include all of those individuals who were players in this intriguing story of development, but selects some of the most notable men and women involved.

In the early years, the whole of North America was a great unknown, and there was an emphasis on documenting the species and conditions of this vast new world. The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were a remarkable time for natural history in North America. There was a great deal of drive and activity among the many naturalists who were in the process of describing and cataloguing the species that exist on the continent. There was considerable cooperation among them as they needed to work together in collecting, exchanging, organizing, and studying the huge influx of new specimens. It was a period of rapid advancement in nature study and knowledge. In some ways this period is a very romantic one, with naturalists describing wilderness areas where huge numbers of various species thrived. The early naturalists saw Eskimo Curlews, Carolina Parakeets, and Passenger Pigeons in abundance. At the time that the nineteenth-century naturalists were collecting specimens, these species were plentiful. Now, due to over-hunting and human-made changes in the landscape, the Eskimo Curlew is down to just a handful (and may be extinct), and the Carolina Parakeet and Passenger Pigeon no longer exist. It is thought-provoking to read about these thriving wilderness areas and realize how greatly man has altered the landscape, making it more sterile and inhospitable to the diversity of life. It attests to the rate at which man is accelerating the pace of species extinction.

At the time when the earliest of these naturalists were in the field and before the use of binoculars, it was common practice to kill specimens, which were then preserved and later examined and studied. This was a way to identify and describe species. However, these early naturalists did not believe in the massacre of large numbers of fauna for sport or profit. They commented on the huge numbers of individuals of various species that were found in North America, but they also warned that in spite of these large numbers, the population could be drastically reduced or even extinguished in a relatively few years if practices of killing vast numbers were continued. Because these naturalists respected birds and other animals so much, they wanted to ensure their survival, and they dreaded the thought of their extinction.

As the nineteenth century drew to a close, there was increasing concern about conserving living natural resources and about creating nature preserves where wildlife and the natural environment would be protected. The focus changed from collecting and describing physical characteristics of birds and other animals to studying their life histories in order to try to understand their needs. This goal, as well as educating the public about its responsibility to care for the natural world and its living resources, is the current objective of natural history studies.