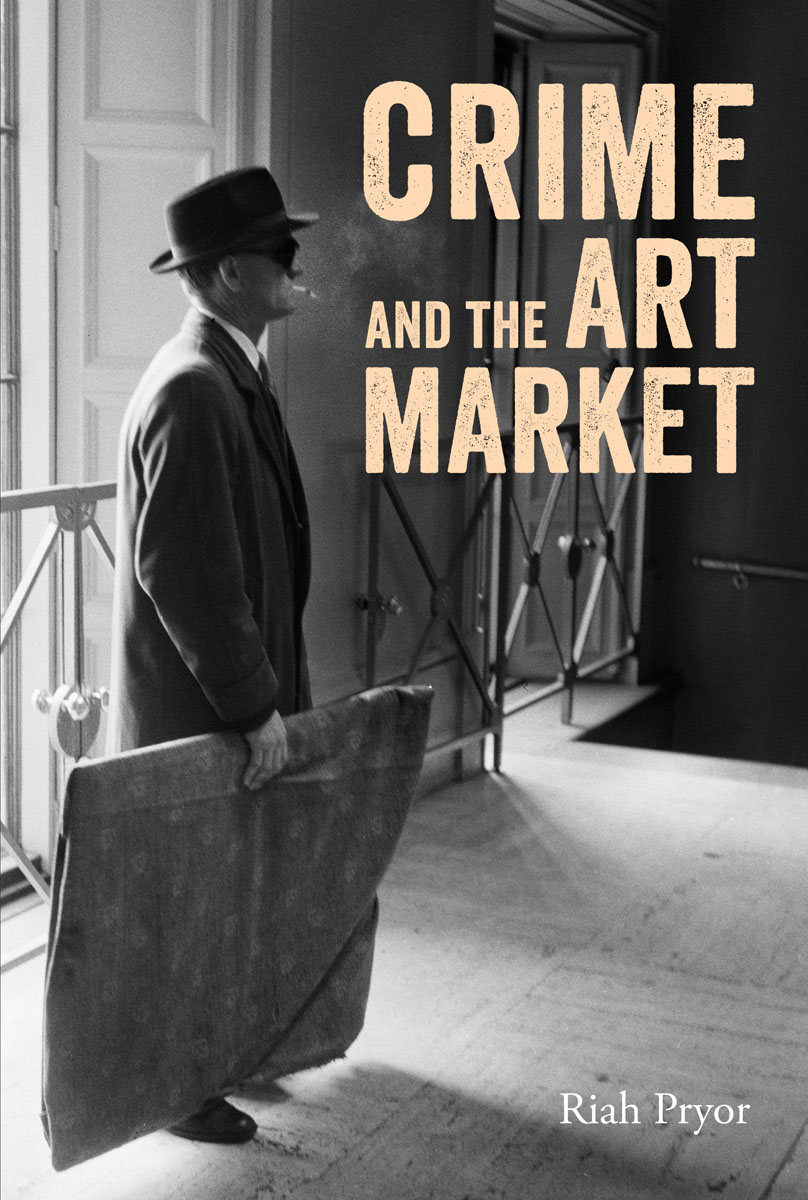

First published in 2016 by

Lund Humphries

16 St Martins Le Grand

London

EC 1 A 4 EN

UK

www.lundhumphries.com

Riah Pryor, 2016

Riah Pryor has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the Author of this Work.

ISBN Hardback: 978-1-84822-171-0

ISBN eBook (PDF): 978-1-84822-190-1

ISBN eBook (ePUB): 978-1-84822-189-5

ISBN eBook (mobi): 978-1-84822-203-8

A Cataloguing-in-Publication record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise, without first seeking the permission of the copyright owners and publishers.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

The first time I stood in an auction house as a journalist, I presumed that every art dealer and collector around me was a suspect waiting to happen. After a few years working as a reseracher in the Art & Antiques Unit of Londons Metropolitan Police Service (at New Scotland Yard), my perspective on the art market was cynical, to say the least.

Readers of mainstream coverage on the subject of art crime will hear the art market described as murky and unregulated, and may similarly share such cynicism. But how accurate, or fair, is this presumption of the art market being guilty until proven innocent? It did not take many more years working as a journalist within the art market for my early views to be challenged. Despite my ongoing interest in reporting on criminal and civil cases involving art works, with every specialist dealer and passionate collector I met, the complexity of the reasons behind art crime became obvious.

This book is an attempt to outline where my opinions are today. There is more at stake than simply determining how many criminals there are in the art market. Under consideration are concerns as to whether the art market, with its opaque structures and secretive ways of doing business, is fundamentally facilitating criminal activity.

To pick the situation apart, one must delve into an intricate network of political, financial, ethical and personal factors, and consider how art crime functions within the market. The extent to which attempts to investigate and prevent the problem compare to other sectors within society also needs to be examined. These tasks equally demand an appreciation of the fact that the art market itself has changed exponentially since study of art crime began.

If misunderstanding is a worrying foundation to begin a book, it would have been far more so, were it not for my friend and former editor, Melanie Gerlis. My ability to write anything substantial on this subject is thanks to everyone at The Art Newspaper, particularly Georgina Adam, and my former colleagues at New Scotland Yard. The following are also thanked for their advice and insights on this project: Lucy Myers and Lund Humphries, Karen Sanig, Janet Ulph, Martin Wilson, Kenneth Polk, Bojan Dobovek, Melanie McFadyean, Anthony Browne, Pierre Valentin, Chris Marinello, Nicholas Brett, Robert Read, Julian Radcliffe, Adriano Picinati di Torcello, Leila A. Amineddoleh, Joe Hill, Judith Prowda and Matthew Paton. Of course, thanks also go to my family (the Pryors and the Palmers) and husband Rob to whom this book is dedicated.

Introduction

CALLS FOR CHANGE

A criminals playground?

As the familiar proverb says: One bad apple spoils the barrel. A 2005 survey considering the impact of new legislation on the antiquities market found that 36 per cent of respondents working in the trade believed the problem of looted antiquities being sold on the art market could be attributed to bad apples. In other words, it was felt that a small sector of the trade was misbehaving and giving the broader sector a bad reputation. Those conducting the survey were unconvinced:

we suggest that this represents a somewhat pious and complacent view on the part of dealers who may well themselves be dealing in illicit antiquities, perhaps unwittingly.

Opinions on the art market and its relationship with criminal activity have not improved since. The US-based economist Professor Nouriel Roubini declared at the 2015 Davos World Economic Forum that regulation was needed in the art market to prevent its exploitation by criminals, reportedly describing how the sector had weaknesses that would not be allowed in other kinds of financial markets, such as equities. The comments sparked debate across the globe: had the sector been allowed to follow its own rules, unwatched, for too long?

Concerns about trade in cultural property and the degree to which the market accommodates criminal activity are in line with broader international discussions around the need for stronger scrutiny of markets in high-risk assets. The political climate for greater transparency and regulation has been accelerating since the social, economic and political upheaval following the 2008 global financial crisis. As societies worldwide feel the hit of subsequent economic measures and the gap between the rich and the poor increases, governments are feeling public pressure to act on issues that are more traditionally linked to the upper echelons of society notably tax evasion, money laundering and corruption.

It is unsurprising that the art market is facing a share of this criticism. The seemingly subjective financial value of cultural property has long proved a hurdle for tighter rules around the art trade, and the stratospheric leaps in prices at the top end of the market, which have risen over the us$100 million mark in recent years (including the sale of Pablo Picassos Les Femmes dAlger, Version O (1955) at Christies, New York, for $179 million in May 2015), has boosted feeling that the art world is not grounded in any objective value system or set of controls. Add to this complex and fluid value system an unprecedented expansion of cross-border trade in art and an ongoing lack of transparency, and it is unsurprising that opportunities for criminal activity in the market appear rife. The seeming proliferation of criminal cases involving forgeries, looted antiquities and the circulation of stolen art in recent years further supports speculation that the industry is in need of greater controls.

This book considers a key question emerging from the image of the art trade as murky: Is the market a criminals playground, open to illicit activity and providing an environment where good and bad apples are one and the same?

SCOPE

A typical reaction to telling someone that you work in the field of art crime goes a little like this: Wow, that sounds interesting what exactly is that?

The scope of the topic is broad. Most commonly, however, coverage of art crime is dominated by forgeries, stolen art, criminal damage against art and the looting of antiquities. However, the use of art in crime also extends to bribery, tax evasion, money laundering and so-called white-collar crimes (although definitions vary, it can be understood as crimes conducted by persons in business or positions of authority

These offences can loosely be organised into the following categories: art as the target for criminal activity (i.e. theft and forgery); art used within crime (where the work of art played a pivotal role within the criminal act, but was part of a broader criminal act, for example in use as collateral within a network trading in drugs); and crimes against art (i.e. vandalism against art). A fourth category, art as a criminal act, can be used to describe works of art that are deemed to be criminal acts themselves (e.g. art investigated as being obscene in terms of its content).

Next page