Albert Einstein - Letters to Solovine: 1906-1955

Here you can read online Albert Einstein - Letters to Solovine: 1906-1955 full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2011, publisher: Philosophical Library/Open Road, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Letters to Solovine: 1906-1955

- Author:

- Publisher:Philosophical Library/Open Road

- Genre:

- Year:2011

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Letters to Solovine: 1906-1955: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Letters to Solovine: 1906-1955" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Letters to Solovine: 1906-1955 — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Letters to Solovine: 1906-1955" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Letters to Solovine

1906 1955

Albert Einstein

Contents

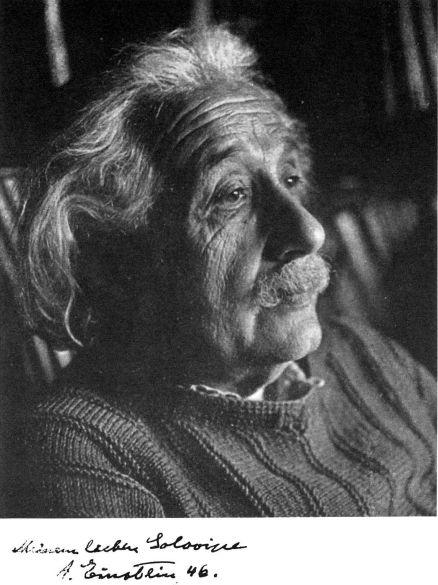

THE AKADEMIE OLYMPIA (known today as the Olympia Academy) was formed in early 1902, soon after the Romanian student Maurice Solovine answered an advertisement that Albert Einstein placed in a Bern newspaper for private lessons in physics. Solovine wanted to be tutored in mathematics and physics, and Einstein needed money. This volume documents the lifelong friendship that developed from that meeting. The ten-page introduction by Solovine outlines the early history of the Olympia Academy and explains how Einstein lost a paying student and gained a philosophical partner. The Olympia Academy eventually included Einstein, Besso, Solovine, and the brothers Habicht, among others. It is all the more fascinating that this group held its time-consuming meetings during the period in which Einstein turned out many of his famous papers. Perhaps most important to relativity theory were the discussions that centered on Machs critique of the Newtonian concepts of absolute space and time.

The correspondence documented here started when Solovine left the group in 1906, and continued until February 27, 1955, less than two months before Einsteins death.

These letters attest to the great importance that Einstein attached to this group and indicate obliquely how important Einsteins study of philosophy was to the development of his physics. In the letter dated April 3, 1953, slightly more than fifty years since its founding, Einstein created a touching ode to the Olympia Academy and sent it to Solovine. This was a result of receiving a card sent from Paris by Habicht and Solovine addressed to the president of the Olympia Academy.

Einsteins social life and obligations are well documented here, as are his trials and tribulations with his ongoing work. There are letters where he expresses self-doubt about his work, as well as others where he is enthusiastic about a new line of reasoning. Other letters comment about his family and the lives of his friends. As a famous person, Einstein felt it was his obligation to secure support for his friends, and he frequently comments upon payments and royalties and how he hopes to help them.

These letters to Solovine, Einsteins dear and close personal friend, paint a very human portrait of the greatest physicist of all time.

Neil Berger,

Associate Professor Emeritus of Mathematics

University of Illinois at Chicago

October 2010

WHEN I WENT TO Berne as a student at the beginning of the century, I had not decided on the subjects that I wished to study. Since philosophy, though unworthy of the distinction today, still held claim to the study of the most exalted problems, I felt strongly inclined toward this subject, but simultaneously I had a burning desire to learn about concrete things, with the result that along with courses in Greek philosophy, literature and philology, I also studied mathematics, physics, and geology as well as a course in physiology in the Faculty of Medicine. By dint of hard work, I managed to acquire during the first year a body of knowledge which was far from enough to bring complete satisfaction but which allowed me to untangle the jumbled ideas that filled my head and to become aware of the paths and procedures through which the mind achieves positive results. My course in experimental physics had been absorbing, but the professor seemed to delight in speaking disdainfully of physical theories. He used to say that physical theories are more or less arbitrary constructions based on hypotheses and that the discovery of new facts undermines them and causes them to collapse, while facts which are carefully studied experimentally and shaped analytically stand as a definitive acquisition of physics and contribute to its continuous elaboration.

But what I found most absorbing were these theories, for they gave me an overall view of nature and a firm basis for the study of philosophy, but I felt incapable of understanding them because of a deficiency in mathematics; still, I tried hard to grasp as much as I could. The discovery of radium caused considerable agitation since it was thought to reverse the principle of the conservation of energy.

Having bought a newspaper and started to walk down the streets of Berne one day during the Easter vacation of 1902, I came to a place which said that Albert Einstein, a former student of Zurich Polytechnical School, would teach physics for three francs an hour. I mused: Perhaps this man could explain theoretical physics to me. I made my way to the house mentioned in the advertisement, walked up to the second floor and rang the bell. I heard a thunderous Herein! and soon saw Einstein appear. The hallway was dark and I was struck by the extraordinary radiance of his large eyes. After I had gone inside his apartment and taken a seat, I told him that I was studying philosophy but wanted also to delve into physics so as to acquire a thorough understanding of nature. He confessed that he, too, had leaned toward philosophy when he was younger, but that the vagueness and arbitrariness that characterizes philosophy had turned him away from it and that he now concentrated exclusively on physics. For two hours we talked on about all sorts of questions and felt that we shared the same ideas and a mutual attraction. As I started to take leave of him, he went along with me and we continued the discussion in the street for about half an hour and agreed to meet the following day.

When we saw each other again, we renewed our discussion of certain questions that we had broached the preceding evening and the physics lesson was completely forgotten.

And when I came to him on the third day, he told me, after we had talked for a while: As a matter of fact, you dont have to be tutored in physics; our discussion of problems that stem from it is much more interesting. Just come to see me and I will be glad to talk with you. I went back many times, and the better I became acquainted with him, the stronger my attachment grew. I admired his singular insight and his surprising mastery of physical problems. He was not a brilliant orator and did not use striking imagery. He outlined his subjects in a slow, even tone but in a remarkably lucid manner. To make his abstract thought more easily understood he sometimes used examples drawn from common experiences. Einstein was a skilled mathematician but he often spoke out against the abuses of mathematics in the hands of physicists. Physics, he would say, is basically a concrete, intuitive science. Mathematics is only a means to express the laws that govern phenomena.

As we were talking one day, I asked him: Dont you think that it would be a good idea for both of us to read one of some great thinkers works, and then discuss the problems dealt with in the work? Thats an excellent idea, he answered. I suggested then that we read a scientific work by Karl Pearson and Einstein eagerly accepted. A few weeks later, Conrad Habicht, whom Einstein had known in Schaffhouse and who had come to Berne to finish his studies with a view to teaching mathematics in the lyce, took part in our discussions. Our dinners were models of frugality. The menu ordinarily consisted of one bologna sausage, a piece of Gruyre cheese, a fruit, a small container of honey and one or two cups of tea. But our joy was boundless. The words of Epicurus applied to us: What a beautiful thing joyous poverty is!

Einstein was a candidate for a license at the time I knew him and was impatiently awaiting appointment. He had to give private lessons in order to live, and pupils were not easy to find; rates were low. One day when we were discussing ways of earning a living, he told me that the easiest way would be to play the violin in the streets. My answer was that if he had really decided to do that, I would begin to learn the guitar and accompany him.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Letters to Solovine: 1906-1955»

Look at similar books to Letters to Solovine: 1906-1955. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Letters to Solovine: 1906-1955 and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.