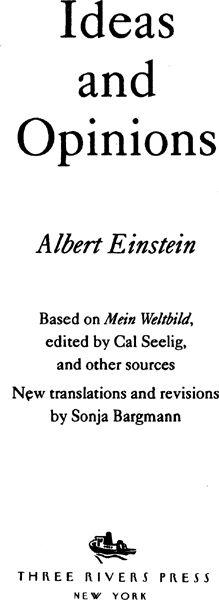

Albert Einstein - Ideas and Opinions

Here you can read online Albert Einstein - Ideas and Opinions full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1954, publisher: Bonanza Books, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Ideas and Opinions

- Author:

- Publisher:Bonanza Books

- Genre:

- Year:1954

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Ideas and Opinions: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Ideas and Opinions" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Ideas and Opinions — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Ideas and Opinions" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

PART I:

PART II:

PART III:

PART IV:

PART V:

Ideas and Opinions represents an attempt to gather together, so far as is possible, in one volume the most important of Albert Einsteins general writings. Until now there have been three major collections of articles, speeches, statements, and letters by Einstein: The World As I See It, translated by Alan Harris, published in 1934; Out of My Later Years (1950), containing material from 1934 to 1950; and Mein Weltbild, edited by Carl Seelig, published in Switzerland in 1953, which contains certain new materials not included in either of the other collections.

Ideas and Opinions contains in the publishers opinion the most important items from the three above-mentioned books, a few selections from other publications, and new articles that have never been published in book form before. It was only with the very kind cooperation of Carl Seelig and Europa Verlag of Zurich and the help of Professor Einstein himself that it was possible to assemble this collection of Einsteins writings from the earliest days to addresses of only a few weeks ago.

Special thanks must be given to Helen Dukas who facilitated the gathering of these articles and to Sonja Bargmann whose contribution is major: she checked and revised previous translations, provided new translations for all other articles not specifically credited, participated in the selection and editing of the entire volume and influenced her husband, Valentine Bargmann, to write the introduction to , Contributions to Science.

Acknowledgments should be made also to the various publishers who made available articles copyrighted by them and whose names may be found with the articles.

IDEAS AND OPINIONS

Written shortly after the establishment in 1919 of the League of Nations and first published in French. Also published in Mein Weltbild, Amsterdam: Querido Verlag, 1934.

As late as the seventeenth century the savants and artists of all Europe were so closely united by the bond of a common ideal that cooperation between them was scarcely affected by political events. This unity was further strengthened by the general use of the Latin language.

Today we look back at this state of affairs as at a lost paradise. The passions of nationalism have destroyed this community of the intellect, and the Latin language which once united the whole world is dead. The men of learning have become representatives of the most extreme national traditions and lost their sense of an intellectual commonwealth.

Nowadays we are faced with the dismaying fact that the politicians, the practical men of affairs, have become the exponents of international ideas. It is they who have created the League of Nations.

An interview for Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant, 1921. Appeared in Berliner Tageblatt, July 7, 1921.

I must redeem my promise to say something about my impressions of this country. That is not altogether easy for me. For it is not easy to take up the attitude of impartial observer when one is received with such kindness and undeserved respect as I have been in America. First of all let me say something on this score.

The cult of individuals is always, in my view, unjustified. To be sure, nature distributes her gifts unevenly among her children. But there are plenty of the well-endowed, thank God, and I am firmly convinced that most of them live quiet, unobtrusive lives. It strikes me as unfair, and even in bad taste, to select a few of them for boundless admiration, attributing superhuman powers of mind and character to them. This has been my fate, and the contrast between the popular estimate of my powers and achievements and the reality is simply grotesque. The awareness of this strange state of affairs would be unbearable but for one pleasing consolation: it is a welcome symptom in an age which is commonly denounced as materialistic, that it makes heroes of men whose goals lie wholly in the intellectual and moral sphere. This proves that knowledge and justice are ranked above wealth and power by a large section of the human race. My experience teaches me that this idealistic outlook is particularly prevalent in America, which is decried as a singularly materialistic country. After this digression I come to my proper theme, in the hope that no more weight will be attached to my modest remarks than they deserve.

What first strikes the visitor with amazement is the superiority of this country in matters of technology and organization. Objects of everyday use are more solid than in Europe, houses much more practically designed. Everything is designed to save human labor. Labor is expensive, because the country is sparsely inhabited in comparison with its natural resources. The high price of labor was the stimulus which evoked the marvelous development of technical devices and methods of work. The opposite extreme is illustrated by over-populated China or India, where the low price of labor has stood in the way of the development of machinery. Europe is halfway between the two. Once the machine is sufficiently highly developed it becomes cheaper in the end than the cheapest labor. Let the Fascists in Europe, who desire on narrow-minded political grounds to see their own particular countries more densely populated, take heed of this. However, the anxious care with which the United States keep out foreign goods by means of prohibitive tariffs certainly contrasts oddly with the general picture. But an innocent visitor must not be expected to rack his brains too much, and when all is said and done, it is not absolutely certain that every question admits of a rational answer.

The second thing that strikes a visitor is the joyous, positive attitude to life. The smile on the faces of the people in photographs is symbolical of one of the greatest assets of the American. He is friendly, self-confident, optimisticand without envy. The European finds intercourse with Americans easy and agreeable.

Compared with the American the European is more critical, more self-conscious, less kind-hearted and helpful, more isolated, more fastidious in his amusements and his reading, generally more or less of a pessimist.

Great importance attaches to the material comforts of life, and equanimity, unconcern, security are all sacrificed to them. The American lives even more for his goals, for the future, than the European. Life for him is always becoming, never being. In this respect he is even further removed from the Russian and the Asiatic than the European is.

But there is one respect in which he resembles the Asiatic more than the European does: he is less of an individualist than the Europeanthat is, from the psychological, not the economic, point of view.

More emphasis is laid on the we than the I. As a natural corollary of this, custom and convention are extremely strong, and there is much more uniformity both in outlook on life and in moral and esthetic ideas among Americans than among Europeans. This fact is chiefly responsible for Americas economic superiority over Europe. Cooperation and the division of labor develop more easily and with less friction than in Europe, whether in the factory or the university or in private charity. This social sense may be partly due to the English tradition.

In apparent contradiction to this stands the fact that the activities of the State are relatively restricted as compared with those in Europe. The European is surprised to find the telegraph, the telephone, the railways, and the schools predominantly in private hands. The more social attitude of the individual, which I mentioned just now, makes this possible here. Another consequence of this attitude is that the extremely unequal distribution of property leads to no intolerable hardships. The social conscience of the well-to-do is much more highly developed than in Europe. He considers himself obliged as a matter of course to place a large portion of his wealth, and often of his own energies, too, at the disposal of the community; public opinion, that all-powerful force, imperiously demands it of him. Hence the most important cultural functions can be left to private enterprise and the part played by the government in this country is, comparatively, a very restricted one.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Ideas and Opinions»

Look at similar books to Ideas and Opinions. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Ideas and Opinions and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.