Acknowledgments

I wish to thank my publisher, Marty Asher of Pantheon Books, for his encouragement.

I am also indebted to my agent, Max Brockman, who recognized the potential of this book, and to Sara Lippincott for her thoughtful and meticulous editing.

BOOKS BY JOHN BROCKMAN

As author

By the Late John Brockman

Afterwords

The Third Culture: Beyond the Scientific Revolution

Digerati

As editor

About Bateson

Speculations

Doing Science

Ways of Knowing

Creativity

The Greatest Inventions of the Past 2,000 Years

The Next Fifty Years:

Science in the First Half of the 21st Century

The New Humanists: Science at the Edge

Curious Minds: How a Child Becomes a Scientist

As coeditor

How Things Are

ABOUT THE EDITOR

John Brockman has edited nearly twenty books and is the author of By the Late John Brockman, The Third Culture, and Digerati: Encounters with the Cyber Elite. He is the founder and CEO of Brockman Inc., an international literary and software agency; president of Edge Foundation, Inc.; and publisher and editor of Edge, a Web site presenting the third culture in action. A well-known computer and Internet entrepreneur and visionary, he and his work are frequently featured in the media.

Einstein When Hes at Home

ROGER HIGHFIELD

ROGER HIGHFIELD is the science editor of the Daily Telegraph in London. He has carried out research at Oxford University and the Institut Laue-Langevin in Grenoble, where he became the first to bounce a neutron off a soap bubble. He is the author of Can Reindeer Fly?: The Science ofChristmas; The Science of Harry Potter: How MagicReally Works; and coauthor (with Paul Carter) of The Private Lives of Albert Einstein and (with Peter Coveney) of Frontiers of Complexity and The Arrow of Time, a best seller that has been translated into more than a dozen languages.

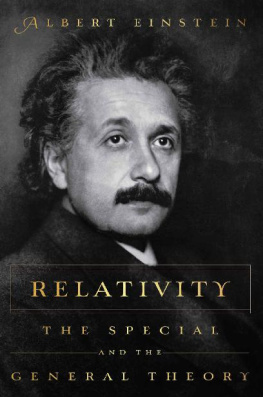

Here is the canonical Einstein: He begins life as a dullard and a dyslexic, yet he overcomes these obstacles to help lay the foundations of quantum theory, to change our view of space, and to transform time. Despite his towering achievements, he shows great humility. He pokes his tongue out for the cameras. He is disheveled. He hates socks. He is an eccentric genius with a warm heart. He is a pacifist (except when it comes to the Nazis). His face is wise and lined, his hair is white and wild; some call it a mane or even a halo. When describing the universe, Einstein resorts to religious terms. He has the aura of a saint. But he also has a dark secret: he invented the atomic bomb.

The popular image of Einstein as archetypal eccentric boffin dates to half a century after the first flowering of his astonishing creative genius. The tangle-haired sage whose image has graced thousands of posters, coffee mugs, and T-shirts is an Einstein well past his scientific best, a faded version of the original. We should bury the sockless dust-ball who rolled around Princeton and restore the creative Einstein.

This is the young Einstein, whom Paul Carter and I attempted to portray in our 1993 book The Private Lives of Albert Einstein, after conversations with relatives and with scholars such as Jrgen Renn, John Stachel, and Robert Schulmann. This is the passionate Einstein. This Einstein had a muscular and powerful build despite his indifference to most forms of exercise. He had regular features, warm brown eyes, a mass of curly black hair, and a raffish mustache. He was good-looking and enjoyed the company of women. They enjoyed his company, too. And, of course, he was a genius. That much was obvious early.

Einstein was not stupid as a child. He did repeat himself, but he was not dyslexic, as is often asserted. Classmates at his primary school taunted him with the nickname Biedermeier (Honest John), most likely because of his blunt manner. But his mother, Pauline, wrote in August 1886 that the seven-year-old was at the top of his class once again and had received a splendid report card. He was brought up in a family that made its living from electrical engineering, an advanced technology of the day.

Despite his love of a religious turn of phrase, Einstein found it impossible to conceive of a personal deity and had no belief in an afterlife. He has said that his reading of popular science ended his religiosity abruptly, at the age of twelve. He decided that the stories of the Bible could not be true and became a fanatical freethinker, convinced he had been fed lies.

He did not invent the atom bomb. He did transform our view of space and time. His great scientific works began with a creative outpouring in 1905, when he was just twenty-six years old. Like almost every other scientist and mathematician, he was at his most productive in his early years.

No one knew the real Einstein better than his first wife, Mileva Mari . Their marriage, from 1903 to 1919, spanned the most important years of his life, yet Mileva is a shadowy figure in many Einstein biographies. Because of a lack of letters from that period and their uneasiness about his first marriage and its many failings, the traditional biographers tended to focus on Einsteins later years. In these hagiographies, in which the assumption is made that a great scientist must have an unwrinkled private life, the old Einstein prevails.

. Their marriage, from 1903 to 1919, spanned the most important years of his life, yet Mileva is a shadowy figure in many Einstein biographies. Because of a lack of letters from that period and their uneasiness about his first marriage and its many failings, the traditional biographers tended to focus on Einsteins later years. In these hagiographies, in which the assumption is made that a great scientist must have an unwrinkled private life, the old Einstein prevails.

A chance to see Einstein afresh came when his son Hans Albert died in July 1973. In a shoebox in a drawer at his home in Berkeley, California, was family correspondence, including love letters from Einstein to Mileva. The collection was so sensitive that the executors of Einsteins estate had gone to court to stop Hans Albert from publishing it; they argued that not even Einsteins son, to whom many of the letters were addressed, should be allowed to reveal such intimate material. Only in recent years have the letters been published, and only now can we see Einstein in his prime, warts and all.

The young Einstein would moan to Mileva that his mother and sister were crass, petty, and philistine. He complained about the mindless prattle of his mothers friends and relatives. His Aunt Julie was a veritable monster of arrogance. His relatives and their hangers-on were people gone soft, turned moldy, whose lives were empty and whose minds had atrophied.

The young Einstein was no respecter of scientific reputations, eithernot least because he had been shunned by the establishment after he graduated from the Swiss Federal Polytechnic School (now called the Eidgenssische Technische Hochschule, or ETH) in 1900. The work of Paul Drude, one of the leading theorists of the day, was stimulating and informative but lacked clarity and precision. Einstein sent Drude a series of objections to his electron theory of metals (in which various properties are explained in terms of an electron gas). Having come up with a similar theory, he felt it quite proper to approach Drude as an equal and point out his mistakes. He threatened to make it hot for Drude by publishing an attack on Drudes theory. Unthinking respect for authority is the greatest enemy of truth, he declared.

Einsteins comments on his instructors at the Polytechnic School were equally biting. One taught clearly but too superficially; another was brilliant and profound but an impenetrable pedant. When Einstein struggled to find a job, he accused his old physics lecturer of thwarting his career by spreading bad opinions of him. He went out of his way to annoy the head of a boarding school where he worked for a short time, and he told Mileva, Long live impudence. Its my guardian angel in this world.

Next page

. Their marriage, from 1903 to 1919, spanned the most important years of his life, yet Mileva is a shadowy figure in many Einstein biographies. Because of a lack of letters from that period and their uneasiness about his first marriage and its many failings, the traditional biographers tended to focus on Einsteins later years. In these hagiographies, in which the assumption is made that a great scientist must have an unwrinkled private life, the old Einstein prevails.

. Their marriage, from 1903 to 1919, spanned the most important years of his life, yet Mileva is a shadowy figure in many Einstein biographies. Because of a lack of letters from that period and their uneasiness about his first marriage and its many failings, the traditional biographers tended to focus on Einsteins later years. In these hagiographies, in which the assumption is made that a great scientist must have an unwrinkled private life, the old Einstein prevails.