MY LAST EIGHT THOUSAND DAYS

Valerie Boyd and John Griswold, series editors

SERIES ADVISORY BOARD

Dan Gunn

Pam Houston

Phillip Lopate

Dinty W. Moore

Lia Purpura

Patricia Smith

Ned Stuckey-French

MY LAST

An American Male

EIGHT

in His Seventies

THOUSAND

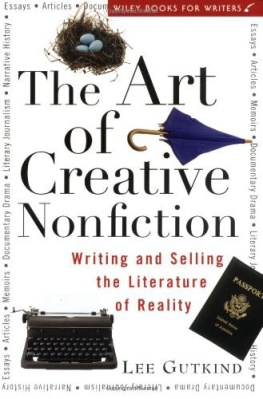

Lee Gutkind

DAYS

THE UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA PRESS | ATHENS

Published by the University of Georgia Press

Athens, Georgia 30602

www.ugapress.org

2020 by Lee Gutkind

All rights reserved

Designed by Kaelin Chappell Broaddus

Set in 11/15 Kinesis Std by Kaelin Chappell Broaddus

Printed and bound by Sheridan Books, Inc.

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence

and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for

Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

Most University of Georgia Press titles are

available from popular e-book vendors.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020937962

ISBN: 9780820359601 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN: 9780820358062 (ebook)

For Michele and Patricia,

my lifelines of love and support

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank the many smart and sensitive people who have read and generously responded to drafts of this book over the years. Your time and insight have been invaluable.

Walter Biggins

Andrew Blauner

Jess Brallier

Becky Cole

David Goehring

Anne Horowitz

Daniya Kamran-Morley

Emily Loose

Dinty W. Moore

Debra Monroe

Jill Patterson

Matthew Sharp

Mike Shatzkin

MY LAST EIGHT THOUSAND DAYS

One

THE MORNING OF MY SEVENTIETH BIRTHDAY BEGAN LIKE ANY other: my alarm blared at 5:30 a.m. Then: grope for the TV remote to change from my Law and Order middle-of-the-night rerun station to CNN for morning news; slip out from under covers, bare feet on floor; stagger into bathroom; relieve myself; brush teeth; splash cold water on my face, closing my eyes to avoid my reflection in the mirror; then back to bedroom; pull on Levis and top from the night before; check iPhone for texts; descend the stairs, knees creaking; yell goddamn, fuck, fuck, fuck because my joints are in morning rebellion; open the front door; bend, wince, retrieve my New York Times; put on coatit is Januaryand head four blocks to Starbucks.

Everything the same, the identical routine I had followed for the past I dont even remember how many years, except maybe for the creaking knees, although I could not recall when they werent creaking, or sometimes also clicking, annoyingly, like a light switch, on/off, every step, clickety-click. I had no idea then, nor have I now, when or why my knee would start or stop clicking, except that that might be the only way to distinguish among my early mornings, the days it clicked and the days it didnt. All else consistent. The morning I was sixty-eight, flowing into the morning I was sixty-nine. And then came the morning I was seventy. Just another year passing, nothing changing. One day later, one day older, but the same life I had been leading and would continue to lead until until until whenever. Didnt matter. Seventy, I had repeated to myself, was only a marker. An unremarkable number.

This, of course, was a goddamn lie. A sham. A way of steadying myself and keeping calm. Or keeping going, even though things werent going too well for me back then, to say the least. The stuff of my lifewhat had, in fact, kept me goingseemed to be gradually falling apart.

For one thing, my mother, Mollie, my most trusted confidante, had diedat a really bad time. Not that there could be a good time for my mother to die, but she had closed her eyes and saidor to be more precise, moanedher last goodbyes to me and the world just five days before my seventieth birthday.

And to be honest, I was having trouble processing that it had actually happened, though I had expected it, and she, and even I on some level, had wished for it. For the past eight months, she had been wasting away before my eyes in an assisted living facility, no longer able to keep her thoughts and words straight, or her balance, or hear much of anything I tried to talk with her about. It had been painful to visit with her, to remember the vigorous woman she once was, the one who ran up and down the stairs, basement to second floor, lugging the bulging family laundry basket, intermittently gossiping on the phone with her gaggle of neighborhood friends, the one who worked 10 a.m. to 9 p.m. Saturdays at our familys shoe store, the one who protected me from my crazy, temperamental, unpredictable father, whom I invariably agitated and feared. It wasnt much of a life anymore for her, and her death should not have been a shock to me.

But I was stunned and unaccepting. I felt like one of those amputees you read about in stories about the severely wounded in warsoldiers in bed in hospitals recovering, who know they have lost legs or arms, but who continue to sense their missing limbs anyway. Phantom limbs, the doctors call it. My mom was a phantom presence to memaybe dead, but not at all gone.

My mother wasnt the only missing limb of my being; there was an entire procession of people in my life and things that had kept me going that had been slipping away, one after another, during that shitty seventieth year. One of my two best old friends, Frank, had just died a few months before. My relationship with my girlfriend of nearly ten years had ended. And my son, my so very brilliant offspring, in whom I had thus far invested more than $250,000 at an exclusive private university for geniuses, where he was studying mathematics and philosophy and where, I had assumed, he would begin research that would change the world, had stopped taking classes with only a semester or two to graduate. I had been aware for a while that he was smoking a great deal of marijuana, but I was obviously in denial about the extent to which he was experimenting with other harmful substances. I guess that parents arent necessarily the last to know about the bad things their children are doing to themselves, but it is easy, when you love someone so deeply and wholeheartedly, to hold on to the hope that, when you do find out, he will grow out of it or he will wake up and see what he is doing to himself (and to his parents!). Still, I had come to realize finally that my son was in deep trouble, not just with drugs but with the mental illness behind his attempts to medicate himself, and as hard as I tried, I hadnt the slightest idea what to do about it.

And then there was my second ex-wife, Patricia, with whom I had been communicating more frequently those days because of our troubles with our son. Shes a hospice nurse, and shes got a great memory and a knack for telling stories, especially about the people she sees dying, which she often shares with me when we talk. I dont want her to tell me all this stuffit creeps me out. But I am a writer, and when she starts a story, I want her to finish it, no matter how uncomfortable it makes me. You should hear her describe the death rattle thing, as she sometimes calls it, when a persons lungs are bursting with fluid and they can no longer breathe, and you can hear this rattle even before you enter their room. Or maybe you shouldnt hear any of this. It would creep you out, too.

To make matters worse, I had been gaining weight. As always, I exercised like crazy, running six or eight miles a day, or as many miles as I needed to stay calm and focused. But gradually, despite my efforts, I had been developing a bit of a pauncha soon-to-be-bulging belly if I didnt put a stop to it. After years of abeyance, I found myself frequently stopping in at the local convenience store after my runs, buying potato chips, cashew nuts, and other snacks, promising myself each time that this was a one-time treata rare deviation from my heretofore careful diet.

Next page