With our short memory, we accept the present climate as normal. It is as though a man with a huge volume of a thousand pages before himin reality, the pages of earth timeshould read the final sentence on the last page and pronounce it history. The ice has receded, it is true, but world climate has not completely rebounded. We are still on the steep edge of winter or early spring. Temperature has reached mid-point. Like refugees, we have been dozing memoryless for a few scant millennia before the windbreak of a sun-warmed rock. In the European Lapland winter that once obtained as far south as Britain, the temperature lay eighteen degrees Fahrenheit lower than today.

On a world scale this cold did not arrive unheralded. Somewhere in the highlands of Africa and Asia the long Tertiary descent of temperature began. It was, in retrospect, the prelude to the ice. One can trace its presence in the spread of grasslands and the disappearance over many areas of the old forest browsers. The continents were rising. We know that by Pliocene time, in which the trail of man ebbs away into the grass, mans history is more complicated than the simple late descent, as our Victorian forerunners sometimes assumed, of a chimpanzee from a tree. The story is one whose complications we have yet to unravel.

Early next morning we left the river and journeyed through a region the scenery of which was exceedingly prettymore picturesque I have hardly ever seen. Hills and valleys, spruits and rivers, grass and treesall combined to present a most charming variety of landscape views.

Major Johnson and I were driving in a cart some distance ahead of the waggon, and, when we arrived at the summit of a small hill, we stopped and waited for Mr Rhodes and Dr Jameson. I was so struck with the beauty of the country there that I decided to choose the site of the farms, which Mr Venter and I were to have in Mashonaland, at the foot of that hill. Mr Rhodes soon guessed my thoughts, for when he came up to our cart he said to me, before I had spoken a word,

Dont tell me anything De Waal, and I shall tell you why youve stopped the cart and waited for me!

Well, why? I asked.

Because you wish to tell me that you have here chosen for Venter and yourself the site of your farms.

Precisely, I replied, you have guessed well.

Well, he said, Ive just been speaking to my friends in the waggon about the grandeur of the place, and I told them that I was sure you would not pass it by without desiring a slice of it.

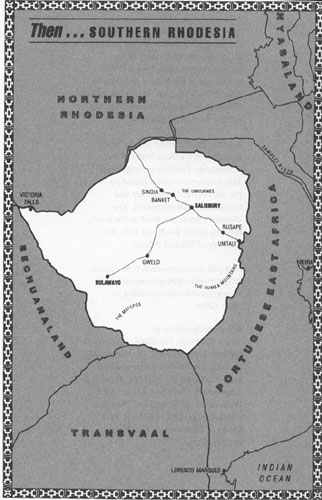

Mr Rhodes then requests Mr Duncan, the Surveyor-General of Mashonaland, who was with us just then, to measure out two farms there, one for Mr Venter and one for myself. I am sure the landed property in that part of the country will soon become very valuable, especially when the railway runsas it soon willbetween Beira and Salisbury.

D. C De Waal, With Rhodes in Mashonaland

This excerpt describes the country near Rusape, on the road between Salisbury and Umtali. The journeys were made in 1890 and 1891, during the Occupation but before the military conquest.

A LITTLE HISTORY

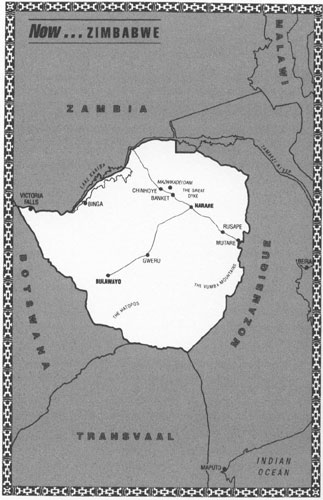

Southern Rhodesia was a shield-shaped country in the middle of the map of Southern Africa, and it was bright pink because Cecil Rhodes had said the map of Africa should be painted red from Cape to Cairo, as an outward sign of its happy allegiance to the British Empire. The hearts of innumerable men and women responded with idealistic fervour to his clarion, because it went without saying that it would be good for Africa, or for anywhere else, to be made British. At this point it might be useful to wonder which of the idealisms that make our hearts beat faster will seem wrong-headed to people a hundred years from now.

In 1890, just over a hundred years from when this book is being written, the Pioneer Column arrived in grassy plains five thousand feet up from the distant sea: a dry country with few people in it. The one hundred and eighty men, and some policemen, had a bad time of it, travelling hundreds of miles up from the Cape through a landscape full of wild beasts and natives thought of as savages. They were journeying into the unknown, for while explorers, hunters and missionaries had come this way, homesteaderspeople expecting to settlehad not. They were on this adventure for the sake of the Empire, for Cecil Rhodes whom they knew to be a great man, for the Queen, and because they were of the pioneering breed, people who had to see horizons as a challenge. Within a short time there was a town with banks, churches, a hospital, schools and, of course, hotels of the kind whose bars, then as now, were as important as the accommodation. This was Salisbury, a white town, British in feel, flavour and habit.

The progress of the Pioneer Column was watched by the Africans, and it is on record they laughed at the sight of the white men sweating in their thick clothes. A year later came Mother Patrick and her band of Dominican nuns, wearing thick and voluminous black and white habits. They at once began their work of teaching children and nursing the sick. Then, and very soon, came the women, all wrapped about and weighed down in their clothes. Respectable Victorian women did not discard so much as a collar, a petticoat or a corset when travelling. Mary Kingsley, that paragon among explorers, when in hot and humid West Africa was always dressed as if off to a tea party. The Africans did not know they were about to lose their country. They easily signed away their land when asked, for it was not part of their thinking that land, the earth our mother, can belong to one person rather than another. To begin with they did not take much notice of the ridiculous invaders, though their shamans, women and men, were warning of evil times. Soon they found they had indeed lost everything. It was no use retreating into the bush, for they were pursued and forced to work as servants and labourers, and when they refused, something called a Poll Tax was imposed, and when they did not pay upand they could not, since money was not something they usedthen soldiers and policemen came with guns and told them they must earn the money to pay the tax. They also had to listen to lectures on the dignity of labour. This tax, a small sum of money from the white point of view, was the most powerful cause of change in the old tribal societies.

Soon the Africans rebelled and were defeated. The conquerors were brutal and merciless. There is nothing in this bit of British history to be proud of, but the story of the Mashona Rebellion and how it was quelled was taught to white children as a glorious accomplishment.

At all times and everywhere invaders with superior technology have subjugated countries while in pursuit of land and wealth and the Europeans, the whites, are only the most recent of them. Having taken the best land for themselves, and set up an efficient machinery of domination, the British in Southern Rhodesia were able to persuade themselvesas is common among conquerorsthat the conquered were inferior, that white tutelage was to their advantage, that they were bound to be the grateful recipients of a superior civilization. The British were so smug about themselves partly because they never went in for general murder, did not attempt to kill out an entire native population, as did the New Zealanders, and is happening now in Brazil where Indian tribes are being murdered while the world looks on and does nothing. They did not deliberately inject anyone with diseases, nor use drugs and alcohol as aids to domination. On the contrary, there were always hospitals for black people, and white mans liquor was made illegal, for it had been observed what harm firewater had done to the native peoples of North America.