The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

Preface

Alcohol is a fact of life. Walk down any street in the Western world and before long your feet will kick against an empty beer can, or your attention will be caught by an alluring advertisement which suggests that alcohol can magically transform your lifestyle. You will pass by an off-licence or two, and there will be a bar or a pub at the corner. Over there are young people drinking at a pavement caf. Perhaps a sad inebriate will lurch against you. But, in the midst of all the casual pleasures of drink, the problems caused by it are more often indoors hidden, or known only to the afflicted family.

This book seeks to present a mix of important facts on this pervasive fact of life. Its aim is to stir and inform debate and to engage attention, but not to take sides. To that end a number of different perspectives are explored. The earlier chapters examine aspects of the history of drinking and of social attitudes towards drinking in different eras and cultures. This material is fascinating in its own right, but it is being deployed with a serious purpose. The worlds image of alcohol, its love or hate for it, and decisions on what to do about this drug, are profoundly coloured by value-laden perceptions of many kinds. Alcohol is a fact around which are created myths, and those myths themselves then become powerful facts.

The book goes on to describe what recent medical science has revealed about the impact of alcohol on the individuals mind and body, the pleasure it gives and the harm it may do, and why for some people it becomes hideously destructive. Alcohol needs to be looked at both in terms of its effects on the individual and in terms of what it does to populations and communities. The spectrum of sciences involved is wide, and their salient findings are here presented in plain language, and illustrated with case studies.

We turn finally to the question of how, in the light of this knowledge, society might in future make a better attempt to deal with this pleasure-giving, somewhat dangerous and ambiguous molecule. How is society to get its pleasure out of alcohol with less likelihood of mass pain?

Most adults anywhere in the world would probably be able to characterize themselves either as drinkers of alcohol or as non-drinkers. Each of those categories, of course, has within it a great mix of persons. The drinkers may be drinking every day and devotedly, or taking no more than a sipped glass of sherry at Christmas. The non-drinker category will include lifetime abstainers, but also those who have stopped drinking because alcohol has made them ill or addicted.

Society seems at present too often to be ill-informed, misinformed or indifferent to the facts on its favourite drug. Thats dangerous. This book is written with respect for everyones unique personal free choice, but in the hope that the facts it lays out will help readers make choices which are well informed and with the myths distinguished from the science.

Acknowledgements

Margaret Annequin proposed this book. Helpful comments on certain draft chapters or particular points were provided by Christopher Cook, Colin Drummond, Kaye Fillmore, Christine Godfrey, Nick Heather, Faith Jaffe, Timothy Peters, Ron Roizen, Robin Room, Mark and Linda Sobell, Jessica Warner, and Harry and Linda Zeitlin. Eric Appleby, Enoch Gordis and Jim Mosher kindly helped with data. Beyond these identified names, immeasurable gratitude is owed to a much wider group of scientists and scholars who have over the years so often and generously shared their wisdom, and given me their friendship. Dwight Heath has given generous permission for the reproduction of the quotations from his work which appear in Chapter 4, and I am similarly grateful to Alan Marlatt for permission regarding quotations reproduced in Chapter 12. The General Service Board of Alcoholics Anonymous has given permission for the reproduction of AAs Twelve Steps, which are to be found in Chapter 8. Sue Edwards gave nurture and detected errors and omissions; Elda Calderone (librarian, Institute of Psychiatry) and Lindsay May Dearlove and Sarah Dodgson (librarians, the Athenaeum) provided bibliographic assistance. Stefan McGrath of Penguin has given me enormously helpful editorial advice and a lot of his time. Bob Davenport provided the best copy-editing I have ever experienced. Finally, I want specially to thank Patricia Davis for her outstandingly competent and patient secretarial support on which I have relied for many years.

Note

This book will at several points use case histories to make live its arguments. Patients, families and doctors in these case histories are all entirely invented, but absolutely true to life.

1 Alcohol, What is It?

This book is neither for nor against alcohol. It considers a particular mind-acting chemical both as a drug and as a social fact. However, it also deals with the myths that have been so abundantly woven around this molecule. And one doesnt get far into this territory before encountering the many stark contradictions in the way people view a substance which has been declared by the World Health Organization to be a cause of cancer, which for the Catholic Church becomes in sacramental wine the blood of Christ, and which meanwhile continues as Western civilizations favourite recreational drug. Alcohol is a pervasive fact of life, but an extraordinary fact pleasurable and destructive, anathematized and adulated, and deeply ambiguous. This introductory chapter gives in non-technical language some basic information on what alcohol is the objective nature of the genie in the bottle.

Alcohol the chemical

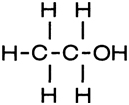

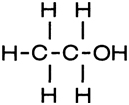

Alcohol in terms of its molecular structure is CHOH and looks like this:

Thus to a spine of two carbon atoms are attached five hydrogen atoms and a hydroxyl (oxygenhydrogen) group. That constitutes a fairly simple structure carrying rather little information, and alcohol has therefore sometimes been referred to disparagingly by biochemists as a stupid molecule. Drawn on a sheet of paper (or more properly projected into three-dimensional space), its structure is much smaller and less interesting than those of such complex mind-acting chemicals as, say, heroin, nicotine or the cannabinol which is the core drug constituent of cannabis.

Alcohol at room temperature is a colourless liquid which in pure form is astringent and unpleasant on the tongue. Dilution makes it less unpalatable, and alcohol and water mix together easily. Spirits are about 40 per cent absolute (pure) alcohol; port, sherry and other fortified wines 1520 per cent; and wine around 12 per cent. A standard beer will be about 4 per cent alcohol by volume, although strong beers can be anything up to 10 per cent. What gives these various beverages their attractive and distinct tastes is not however their alcohol (diluted or otherwise), but the chemicals which have got into them in the course of production. It is possible to produce a beer from which nearly all the alcohol has been extracted and which still tastes reasonably like beer. But take out even a little of the complex flavouring given by sugar, hops, barley and so on, and the residual drink will be a pale imitation or even a parody of the original. Put unkindly, it is the dirt in the drink which makes it attractive to the nose and the palate, and which turns a mixture of alcohol and water into a good beer, a fine wine or a famous malt whisky. Vodka is relatively free from contaminants, and hence relatively odourless and tasteless.

![Scott C (Christopher) Martin - The Sage Encyclopedia of Alcohol Social, Cultural, and Historical Perspectives. 1 [A - D]](/uploads/posts/book/102244/thumbs/scott-c-christopher-martin-the-sage.jpg)