To be a good writer, you must have the paradoxical trait of being a gregarious loner. Marcel Proust claimed that he needed to leave his friends so he could truly be with them; while thinking and writing about his friends, he communicated with them far more thoroughly and excitingly than when he was with them at a party.

As a writer you need a strong sense of independence, of being and thinking on your own so go ahead, work alone. I will give you a lot of advice, but you need not take it. Especially when you disagree, you will formulate your own principles. No matter what advice I suggest in this book, which is designed to be a fiction workshop you can attend on your own, you ought to write freely. Ought and free don't seem to fit together, and that's another paradox of writing: If you can incorporate several writing principles and yet retain and even advance your independence of writing, you've got it made.

Ultimately, write any way that gives you a sense of freedom. What a teacher and a fellow workshopper might discourage as a vice might, through practice, become a virtue.

So even before you continue with this book, with its writing assignments and its advice on writing fiction, you might let yourself write absolutely anything for a couple of weeks a hundred pages, let us say to see if some interesting patterns emerge. That is what I did at first. I avoided advice on how to write, and I wrote several hundred pages of drafts, filled with silly puns and opinions, arbitrary plots and memories. I avoided letting anybody cramp my style. However, I think that I avoided advice and workshops a little too long; some lessons that I learned on my own, I could have learned faster from some good advice. That's why I hope that the basic principles of writing fiction outlined here, with exercises for how to implement them, will help you become a more productive fiction writer.

HOW TO USE THIS BOOK

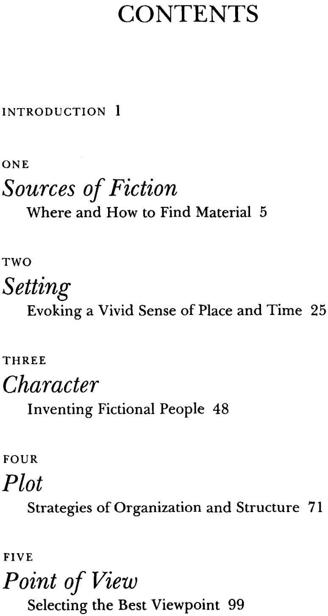

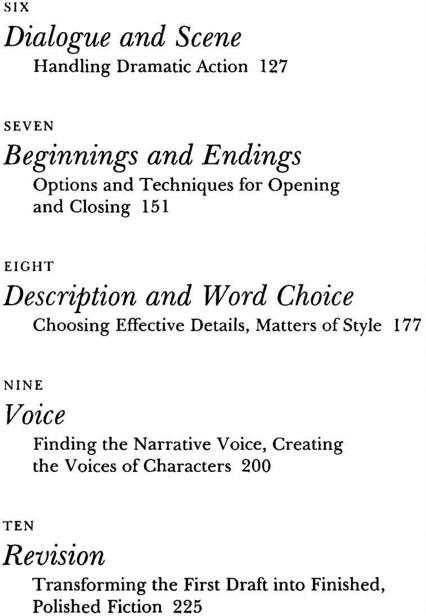

It's simple. The chapters first give you some basics of the elements of fiction. We cover how the elements work and how you can use them in your fiction. The discussions are not meant to be definitive, but orientational.

At the end of each chapter are a dozen or more exercises, some of them calling for brief sketches, a sentence or a paragraph long, some two or three pages long. Do the exercises with an open mind. Don't dismiss them as too simple or too complicated. There are all sorts of finger exercises to keep you in shape in writing, just as there are scales in music. So get into shape, and stay there. When you get ready to write, or you are between writing projects, you certainly can benefit from exercises, no matter how advanced a writer you are. Keep the channels between the brain and the fingertips open let your neurotransmitters happily leap in the direction of the page.

As you do the exercises, concentrate on the task. Don't strive for prettiness, unless that's the assignment. Strive for clarity. Communicate your thoughts and images as directly as possible. Now and then, for a change of rhythm, you may shroud things in long sentences and rich language, but in general, there's nothing more effective than a succinct, straightforward way of putting things. If you aren't direct, on the other hand, don't worry. You will have time to go back and cross out the imprecise words and put in better ones, until you are satisfied. In drawing, some people use a lot of lines to get at the expression on a person's face; some use few or only one. No matter what, give us a world. Don't rely on adjectives of aesthetic judgment because these are abstractions. Instead of saying "ugly" or "wonderful," give us pictures to that effect. Show us what you mean, don't tell us what you want to mean.

The principle with exercises: You get out of them as much as you put in a little more, actually. If you like an exercise, do it several times. A painter may sketch a face a dozen times, and each time is new. The French writer Raymond Queneau wrote Exercises in Style as ninety-nine variations of one simple event: In a bus, a man steps on another's toe. If you don't like something, still give it a try. Don't use your dislikes as obstacles. It's only too easy to find obstacles.

After each exercise, you may ask: How do I know whether I have done it correctly? In a workshop, your peers can tell you what you've missed. If you work alone, you must do it yourself. I'll simplify it for you and ask you questions to consider. Don't read these questions until you are finished with the exercise. Keep them in mind as you read over what you've done. Revise or rewrite your exercise until you get it right. There's a point at which you know that you've done your best, given the limited time you have.

So go back over what you've completed, not so much for what you've done wrong as for what you could do right, more right. Don't work on developing a self-critical that is, self-inhibiting consciousness; do work on developing a sense of where you can jump back in and draw one more line that'll give life to what you already have down or where you could delete a line that may obscure our view of a good line you've drawn.

How much time should you spend on each exercise? I'd say twenty to thirty minutes should be enough. If something stimulates you, of course, keep going, up to an hour. Beyond that, if an exercise has struck a strong chord in you, I'd say you are no longer doing an exercise but writing a story. Great. That'll be the fringe benefit to doing the exercises: You will examine many things, turn many stones and find your treasures. Still, discipline yourself to go back to the exercises and finish them outside of your story writing time.

If you spend five to six hours on exercises in each chapter, you could be through with this book in two months. It would be ideal to spend an hour a day, regularly, so that by the time you finish this book, you will have acquired the writing habit. This habit is the rare kind that is beneficial. It helps you sort out your impressions, memories, thoughts, fantasies, and that should be healthy. Something in the movement of fingers on the keyboard enhances thought. I may not be particularly thoughtful as I write, but much more than if I were simply staring out the window. Some philosophers walked to think more clearly; they belonged to the peripatetic school. Walking provided them with a good flow of blood and oxygen, and with a sensation of doing, moving, going. Fingers pull your thoughts forward. Fingers are in some ways an extension of your brain, with a lot of cortex associations at their trigger. Get them going!

You don't need to wait for inspiration to write. It's easier to be inspired while writing than while not writing, so you don't need to be inspired to sit down and begin. You don't need to be "in the mood." I think you will benefit if you don't worry about moods: One, you will get in the habit of writing under any circumstances; two, since writing reflects your mental state, you will have a diversity of moods in your piece. The diversity will make your writing more interesting. You are depressed? Fine, perhaps you can portray a depressed character. Elated? Don't waste the mood on celebration. Convey it onto the page. Many pieces suffer from moodlessness; perhaps the writers are willing to work only when they are calm.

Ultimately, talk about talent, inspiration, genius, is a distraction. Sit down and do it! Whenever you lack an idea, use some of the exercises in this book they should keep you busy.