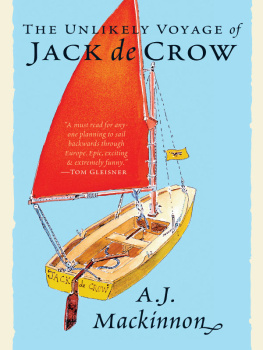

A.J. Mackinnon

Prologue

And whatten wull ye leave to your own bairns and wife,

Edouard, Edouard?

The Warldes room! Let them beg through life!

Alas and wae is me, O!

Scottish ballad

I am eight years old and have just been sent by my older brother Richard to go and find as many rolls of toilet paper as I can. Youre the youngest, he has explained, and cant get into as much trouble as I can. Off you go.

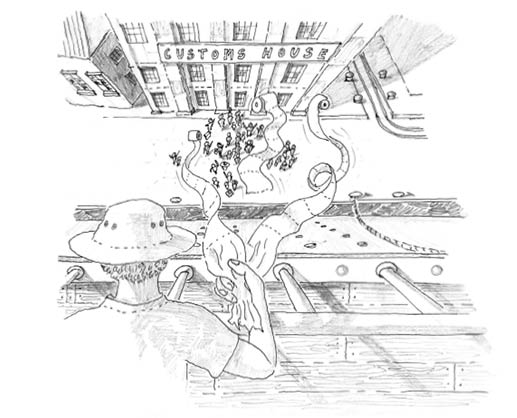

I wind my way through the white labyrinth of the ships interior, dodging passengers and a narrow-eyed ships steward while I visit every bathroom I can find. I return to the upper deck with ten rolls of loo paper and find that it is almost too late. There is now a gap of oily green water between the cliff of the liners side and the Sydney quay and there is a strong smell of diesel. Between us and the crowds on the quay is a festoon of coloured streamers, red and green and blue and yellow, thousands of them fluttering in the breeze and stretching tighter and tighter across the widening gap until they begin to break and curl up.

Richard, unwilling to fork out for the streamers from the ships shop but ever ingenious, now has what he needs. He grabs the loo rolls from me and tells me to hold all the dangling ends of tissue paper. Then he lobs each roll one by one in a true cricketers throw right across the gap in ten soaring arcs of fluttering paper. Three rolls hit home among the crowd and I am almost sure that one elderly woman collapses from a blow to the head. I turn to grin nervously at Richard but he is not there. His figure can be seen ducking away through the crowds along the railings. I wonder briefly why. Two seconds later I turn the other way to find that the ships steward is bearing down on me, more narrow-eyed than ever. Richard is usually right, but in one matter I now suspect he might be mistaken. Sweet-faced and cherubic I might be, but, from the expression on the stewards face as he pushes his way along the crowded deck, I doubt that I am immune to the wrath of the authorities after all. Abandoning the loo rolls, I flee. I am not happy

*

I was pretty unhappy to be there in the first place, to tell the truth. A few months earlier our parents had broken the news: the whole family would be uprooted from our settled existence in Wollongong, New South Wales, and put on a ship bound for England. When first told the news, all four of us Richard and my two sisters and I had burst into tears and protestations at the unfairness of it all. We had cried for the two months leading up to the departure, we had howled in the back of the car as we drove to Sydney for the farewell, and we had stormed and sulked as we were pushed up the gangplank to the glacial bulk of the Arcadia.

But not long after hurling the illicit streamers, the protestations died on my lips. Even when I found Richard on one of the upper decks just as we were passing beneath the Sydney Harbour Bridge and he managed to convince me that the soaring funnels above us would be knocked off by the bridges too-low-seeming span, thus killing us all, I didnt care as much as I ought to have. I had caught the romance, the danger, the fizzing uncertainty of being a traveller it seemed a good way as any to die.

From that moment the magic of seafaring, of proper old-fashioned voyaging, has never left me. Tin trunks. Luggage labels. Ships railings. Deck quoits. Crossing the line. Albatrosses. But the element that really soaked into my young mind was the slow turning of the great globe beneath our bow, day and night, mile by mile, week after week, latitude by latitude, port by port. Table Mountain. The Canary Islands. The fabulous bazaars of Casablanca, where I purchased with my pocket money the chief treasure of the whole trip, namely a plastic pen which, when tilted, sent a tiny camel gliding across a background of date palms and desert dunes. Back onboard there was a large map of the world on the wall of the pursers deck where our progress was marked daily by a little blue and white pin. Each day, Richard and my sisters and I would note our minute but steady progress.

The time spent in England was a childs dream: castles, oak trees, snow and duffel coats, squirrels in Regents Park and pigeons in Trafalgar Square. And then, two years later, there was the return trip to Australia and the whole turtle-torn, sun-wheeling voyage in reverse.

In later years, I could barely bring myself to fly. It felt like cheating. I wasnt doing things properly. I was arriving at the other end having skimped on things along the way. This view of the world was crystallised when I came across an old Scottish ballad in which a young man is to be exiled for killing his father. When asked what

he will leave to his own bairns and wife, he replies bitterly, The Warldes Room! Let them beg through life! The line is ironic, of course, but even so the Warldes Room! As though there were indeed a whole wide world to inherit, a great round, windy ball of a place, deep and bright as a glass sphere, solid as a bowling ball.

The phrase suggested something else to me too, quite different. The Warldes Room in my head looks like this. It is a spacious room in a quiet house with Sunday morning sunlight streaming in the bay windows and touching the writing desk. On the desk is a large atlas open at a particular page. This is mainly green and blue, criss-crossed by lines of latitude and longitude. It shows the whole world from pole to pole, from east to west. Tahiti is just across from Peru, and Peru is just down from Canada, a mere kayak trip away. And look! Heres a sprinkling of islands that Ive never heard of, opal speckles on the blue. And heres a swathe of wrinkled mountains frosted with snow with scarcely a vowel in their names to soften the craggy spikes of consonants. And best of all, there are dotted lines everywhere, swooping in swallow-curves across oceans as shipping lanes, tracing minute red threads as roads or spidery millipede tracks as railways. Its that easy. It is quite small and manageable a place, after all, this world, and theres no need to resort to noisy aeroplanes and acres of grey tarmac. In fact, theres no room at all for such pragmatic ugliness, no room for anything more than the desk and the atlas in the still sunshine. This is the Warldes Room.