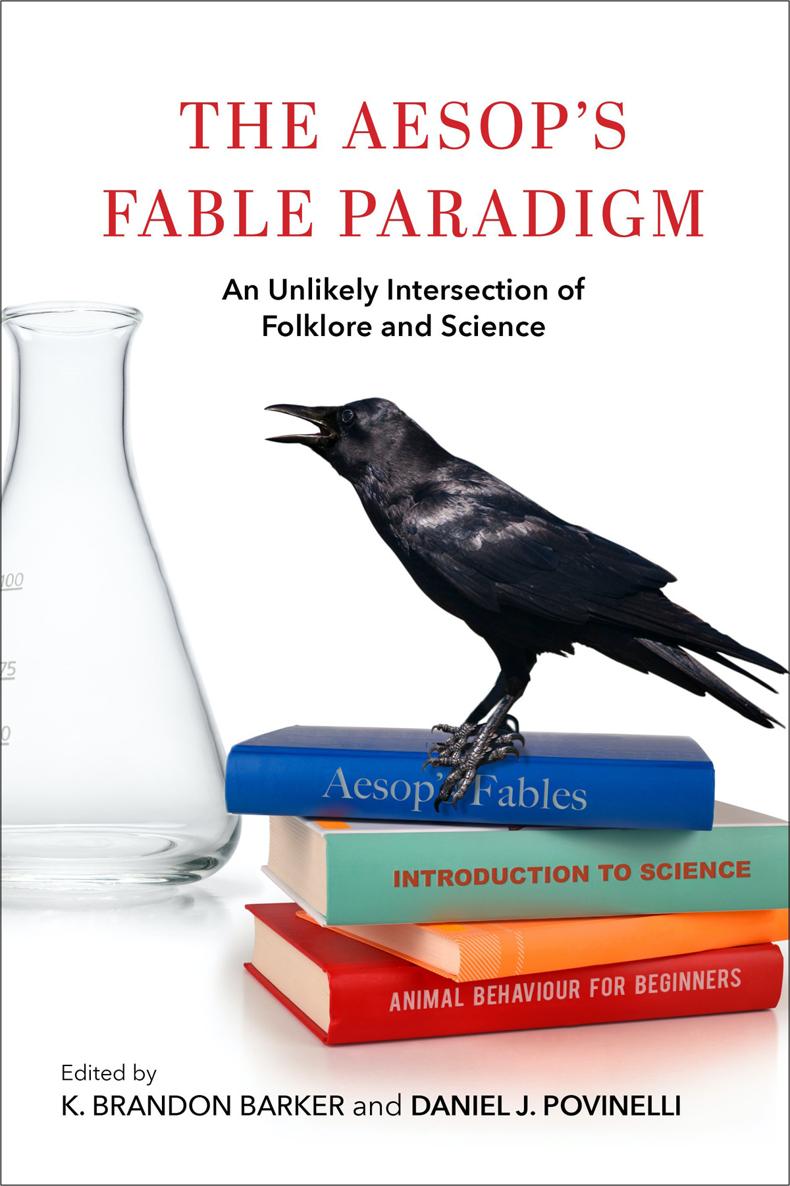

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.org

2021 by The Trustees of Indiana University

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

First printing 2021

Cataloging information is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-253-05922-2 (paperback)

ISBN 978-0-253-05923-9 (ebook)

CONTENTS

Preface

Introduction: The Perplexities of Water / Daniel J. Povinelli and K. Brandon Barker

1.The Animal Question as Folklore in Science / K. Brandon Barker

2.The Early Tradition of the Crow and the Pitcher / William Hansen

3.Going Meta: Retelling the Scientific Retelling of Aesops the Crow and the Pitcher / Laura Hennefield and Hyesung G. Hwang with Daniel J. Povinelli

4.Anthropomorphomania and the Rise of the Animal Mind: A Conversation / K. Brandon Barker and Daniel J. Povinelli

5.Fabling Gestures in Expository Science / Gregory Schrempp

Conclusion: Old Ideas and the Science of Animal Folklore / K. Brandon Barker and Daniel J. Povinelli

Appendix: Doctor Fomomindos Preliminary Notes for a Future Index of Anthropomorphized Animal Behaviors / Daniel J. Povinelli and K. Brandon Barker, with special assistance from Marisa Wieneke and Kristina Downs

Index

I f life is like a carriage ride, and Deathpersonified and prettyrides along, what about the horses? We know. There are always distractions along the way, so many things to see. The schoolyard charms. The fields of grain delight. The chilling breeze distracts. But it is the horses heads, after all, that keep the poet pointed toward eternity. And because they are captive to the joyride, the horsesblinders in placeare likewise destined for a journey with no end. This book runs parallel as it explores the way that scientific storytellers (quite poetical themselves) drive animals on a never-ending journeyor more correctly, a questtoward a goal that the animals cannot achieve. That goal? Nothing less than eternity.

A gently updated version of a special issue of Journal of Folklore Research originally published in 2019, this book concerns a recent (and ongoing) stage of the quest. In the Aesops fable paradigm, scientists have wrangled The Crow and the Pitcher into a (thus far) unending series of scientific experiments to test crows for insightful understanding of the physical properties of water displacement. In the fable, a thirsty crow drops stones into a partially filled pitcher of water to raise the level and take a drink. In the experimental paradigm, a test tube replaces the pitcher, and a tasty worm, lazily floating, replaces the sip of water. As striking as this juncture is, as much as its initial vista amazes, we shall not stay long. Boredom (or in this case, skepticism) arises, and new routines (read: scientific variants) are on the horizon. Since 2019, the quest has continued. And like any other stagecoach line, new animals have joined the team.

In a recent study with parrots, one group of scientists deployed a trick test tube in which the waters could never rise, no matter how many pebbles were dropped inside. The scientists decided the parrots did not evince true causal understanding of water displacementeven though in other cases, when the parrots were not tricked by the experimenters, the parrots were able to raise the water level and retrieve the food reward. The whole thing was enough for the authors to clip the term paradigm and announce that higher-order, insightful understanding of water displacement is not required for solving Aesops Fable (Schwing et al. 2019, 447). Scientists may find it striking that parrots have joined the team. Folklorists may find it striking that fables are now meant to be solved. Riddles, sure; jokes, maybebut fables?

In another recent study, elephants (what took so long?) joined the procession. Twelve zoo-housed elephants were tested in the floating-object taska related, previously used paradigm in which orangutans learned how to spit water into a tube to retrieve a floating peanut. Only one of the twelve elephants tested solved the task, but surely that is not the point. As the authors remark, The cognitive abilities underpinning [elephants] ability to solve the floating water task remain unclear (Barrett and Benson-Amram 2020, 310). Take notice. If the Aesops fable paradigm teaches us nothing about animals minds anyway, then both folklorists and scientists can skip the results and proceed directly to Doctor Fomomindos ever-expanding Folk Motif-Index of Animal Cognition (FOMANCOG) in the back of this book; search for entries such as elephant funeral rituals (A2b.3.), the drunken elephants (D2a.1.), or elephants making fly-swatters from sticks (B1f.); and see that elephants are far too central a fixture in fables and folklore to have been left out for this long.

Folklorists will be happy to know that we have returned to the origin story of these paradigms. Like Athena born from Zeuss skull, the Aesops fable paradigm grew out of the earliest floating-object studies of the aforementioned spitting orangutans. Much dust was kicked up over the fact that those orangutans had not actually dropped stones to retrieve their food rewards, so they could not rightfully lay claim to solving the fable of The Crow and the Pitcher. But separation is invariably followed by return, and orangutans have now rejoined the team. (Are we going in circles?) This time, one orangutan solved the floating-object task by spontaneously spitting into a completely dry vessel holding a peanut (DeLong and Burnett 2020, 338). That it be dry was essential. Water, sparkling before spitting begins, might inadvertently prime the pump of orangutan expectorate. Alas, spontaneity being what it is, scientists must move on down the line: The mechanism underlying [the orangutans] success remains unclear. This variant did show that latency to spit water into the tube decreased exponentially across sessions (327).

No, questing minds cannot linger in the past, so humanoid robots have been tested too. Futurologists will be pleased to know thatprogrammed with the underlying causal principlesat least one robot has solved Aesops fable (Bhat and Mohan 2020). To be clear, the robot did not conjure generalizable displacement physics, so the quest must continue into the futurists futuregood news for anyone who was getting bored, or ethically concerned, with the animal routines. Folklorists might smile on learning that this particular robot did not perform any new morals for the fable. Alas, there can be no doubt that robot morals are just around the next bend.