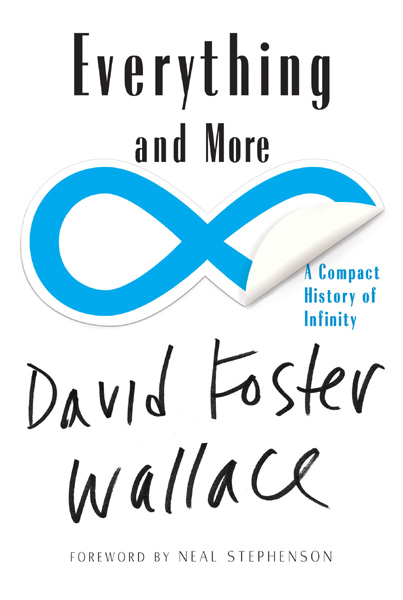

DAVID FOSTER WALLACE

Everything

and More

A Compact History of

ATLAS BOOKS

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

NEW YORK LONDON

Copyright 2003 by David Foster Wallace

Introduction 2010 by Neal Stephenson

All rights reserved

First published as a Norton paperback 2004; reissued 2010

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

Production manager: Julia Druskin

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wallace, David Foster.

Everything and more : a compact history of infinity / David Foster

Wallace.1st ed.

p. cm. (Great discoveries)

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 0-393-00338-8

1. InfiniteHistory. I. Title. II. Series.

QA9.W335 2003

511.3dc21

2003011415

ISBN 978-0-393-33928-4 pbk.

ISBN 978-0-393-24199-0 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue,

New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London WIT 3QT

For my mother and father

Contents

Neal Stephenson

W hen I was a boy growing up in Ames, Iowa, I belonged to a Boy Scout troop whose adult supervisionconsisting almost entirely of professors from the Iowa State University of Science and Technologydevised the following project for us to pursue when not occupied with dodgeball and clove hitches. One of the scouts dadsan eminent professor of agricultural engineeringobtained, from a lab in his department, a sack of genetically identical corn kernels, carried them across campus, and handed them off to one of the other scouts dads: a physicist employed by the Ames Laboratory. This was an offshoot of the Manhattan Project. The uranium enriched at Oak Ridge, and used in the first atomic bombs, had been refined from its ore by a process developed at Ames. Dad #2, who had been present at the startup of the worlds first atomic pile in a racquetball court at the University of Chicago, carried the seeds into a hot room buried a couple of stories beneath one of the Ames Labs buildings and handed it off to a mechanical arm that carried it behind a thick wall of yellowish lead-laced glass and set it down in the vicinity of something that was radioactive. After a certain amount of time had passed, he retrieved the irradiated seeds and brought them to the next meeting of our scout troop and distributed them to the boys. I distinctly remember looking at the kernels in the palm of my hand and noting that they had been washed with paint or ink of two or three different colors, and, though the color code was not explained to us (not, at least, before the expiration of my attention span), I caught the spoor of the scientific method and guessed that different batches had been exposed to greater or lesser amounts of radiation. In any case, we were directed to take these seeds home and plant them and water them. In a few weeks time, we would bring the results to a meeting where two prizes would be handed out: one for the tallest, healthiest corn plant, the other for the weirdest mutation. And indeed we ended up with both: proud stalks that would do any Iowa farmer proud, and plants, in many cases quite beautiful, that were scarcely recognizable as belonging to the relevant taxonomic phylum. If anyone had asked us do you imagine that other scout troops in other towns are doing anything remotely like this we would, after some higher-brain activity, have guessed no. No one asked, however, and so our lower brains assimilated the whole scenario as normal, like playing catch and making smores.

I draw the readers attention, in other words, to the phenomenon of the Midwestern American College Town, which, in a completely self-aware tip of the stylistic hat to David Foster Wallace, I will denominate the MACT. In 1960, when I was six months old, my parents and I moved to the archetypal, if somewhat larger-than-normal, MACT of Champaign-Urbana, Illinois, so that my father could get to work on his PhD. Two years later, when David Foster Wallace was six months old, his family moved to the same town on the same errand (his dad is a philosopher, mine an electrical engineer). He and I lived in the same MACT only until 1966, when my family moved to the smaller, but no less quintessential, MACT of Ames. I never met him, unless we happened to share a slide or a swingset in some Champaign-Urbana park. Each of us went to Massachusetts for higher education and then landed for a while in a different MACT: Iowa City in my case, Bloomington-Normal, Illinois, for DFW.

The irradiated-corn anecdote might have already said everything there is to say about the culture of the MACT, but, since DFW and I seem to have been MACT products all the way, there are a few particulars that might be worth drawing out in a more discursive manner. So here goes.

People who often fly between the East and West Coasts of the United States will be familiar with the region, stretching roughly from the Ohio to the Platte, that, except in anomalous non-flat areas, is spanned by a Cartesian grid of roads. They may not be aware that the spacing between roads is exactly one mile. Unless they have a serious interest in nineteenth-century Midwestern cartography, they cant possibly be expected to know that when those grids were laid out, a schoolhouse was platted at every other road intersection. In this way it was assured that no child in the Midwest would ever live more than  miles from a place where he or she could be educated. Secondary schools were presumably sited according to some less rigid scheme, and universities were generally doled out two to a state. According to a convention that obtains pretty consistently across all states west of Ohio, a given state, call it X, is allotted a University of X and an X State University. University of X has been a University, as opposed to a College, from its inception and generally houses all of the prestigious Arts-and-Sciences departments, the law school, and the medical school. X State University frequently started out as X State College and only acquired the more august University designation within the second half of the twentieth century. It is, more often than not, a land-grant institution, practical-minded, skewed toward agricultural, veterinary, and engineering departments while showing a decent respect for the liberal arts.

miles from a place where he or she could be educated. Secondary schools were presumably sited according to some less rigid scheme, and universities were generally doled out two to a state. According to a convention that obtains pretty consistently across all states west of Ohio, a given state, call it X, is allotted a University of X and an X State University. University of X has been a University, as opposed to a College, from its inception and generally houses all of the prestigious Arts-and-Sciences departments, the law school, and the medical school. X State University frequently started out as X State College and only acquired the more august University designation within the second half of the twentieth century. It is, more often than not, a land-grant institution, practical-minded, skewed toward agricultural, veterinary, and engineering departments while showing a decent respect for the liberal arts.

Normal Schoolsthe third tierwere post-secondary institutions whose purpose was to train the teachers who would staff those every-other-mile schoolrooms on the Cartesian road grid. The same inflationary pressure that turned X State College into X State University eventually caused these to get promoted to University of [geographical modifier] X or [geographical modifier] X University, which is how we got the University of Northern Iowa, Eastern Illinois University, and many others.

The result is a network of public universities, typically situated in small cities (population, say, between twenty and two hundred thousand) and scattered about the upper Midwest at intervals of approximately one tank of gas. Precisely because of their proximity (spang in the middle of their catchment areas); their unprepossessing rank in the academic hierarchy; their practical, down-to-earth emphases; and their athletic teams, which entertain the surrounding areas, which are too sparsely populated to support professional squads, these institutions have escaped the censure/taint of elitism or ivory towerism that, deservedly or not, tends to get slapped onto private, coastal universities by those elements of society who, when depicted cinematically, are generally shown brandishing torches and pitchforks. This may have changed during the twenty-first century because of the politicization of science, but none of that existed in the MACT of the mid- to late twentieth century, when most peoples attitudes toward science were shaped more by antibiotics, the polio vaccine, and moon rockets than current this-cant-be-happening controversies over evolution and global warming.

Next page

miles from a place where he or she could be educated. Secondary schools were presumably sited according to some less rigid scheme, and universities were generally doled out two to a state. According to a convention that obtains pretty consistently across all states west of Ohio, a given state, call it X, is allotted a University of X and an X State University. University of X has been a University, as opposed to a College, from its inception and generally houses all of the prestigious Arts-and-Sciences departments, the law school, and the medical school. X State University frequently started out as X State College and only acquired the more august University designation within the second half of the twentieth century. It is, more often than not, a land-grant institution, practical-minded, skewed toward agricultural, veterinary, and engineering departments while showing a decent respect for the liberal arts.

miles from a place where he or she could be educated. Secondary schools were presumably sited according to some less rigid scheme, and universities were generally doled out two to a state. According to a convention that obtains pretty consistently across all states west of Ohio, a given state, call it X, is allotted a University of X and an X State University. University of X has been a University, as opposed to a College, from its inception and generally houses all of the prestigious Arts-and-Sciences departments, the law school, and the medical school. X State University frequently started out as X State College and only acquired the more august University designation within the second half of the twentieth century. It is, more often than not, a land-grant institution, practical-minded, skewed toward agricultural, veterinary, and engineering departments while showing a decent respect for the liberal arts.